I am currently writing a biography of Herman Melville’s 1851 novel, Moby-Dick. The most important thing I have learnt is that Moby-Dick is not – as is often presumed – a difficult book. I claim this on the basis of those who read it, how they did so and what they took from it in the first decades of its life.

Moby-Dick has a fearsome reputation: dense, time-consuming, boring and bizarre. This reputation (although not absolutely unfair) was initially fabricated by a subset of “elite” Anglo-American academic readers in the 1920s to separate it from the very people who had previously sustained its existence.

In 1994, literature professor Paul Lauter wrote an article that showed how nationalist scholars, looking to forge an American tradition, elevated Moby-Dick to the status of a classic to exclude non-specialist readers.

But earlier readers knew Moby-Dick for what it was: an extreme and ambitious form of popular genre fiction, like science fiction or fantasy, known as the “sea romance”.

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

A romance meant something different in 1851 to what it does now. According to Noah Webster’s Dictionary, then the go-to reference, a romance was “a fabulous relation or story” that went “beyond the limits and facts of real life, and often of probability”.

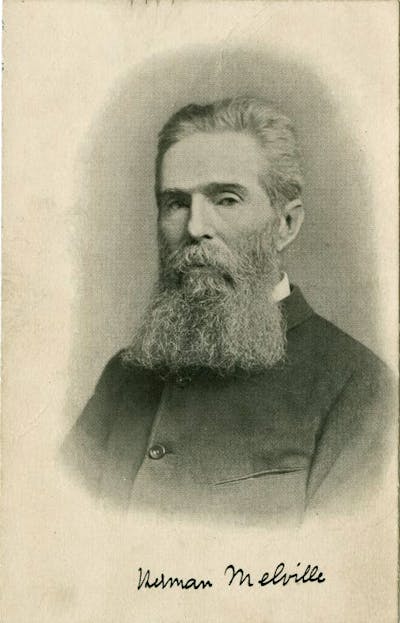

Melville was at this time a literary celebrity after his loosely non-fictional debut Typee (1846) became a transatlantic bestseller for its exotic descriptions of South Pacific captivity. In a letter to his publisher, he wrote that Moby-Dick was a “romance of adventure, founded upon certain wild legends in the southern sperm whale fisheries”.

You could assume that Melville was being cynical – to sell the book, he misrepresented it as having more commercial potential than he thought it did. But I think he was in earnest.

The novel’s initial public was, broadly, found among the professional middle classes in America, who had a taste for this genre, dreaming of faraway places while chained to their desks. I know this because I have tracked down around 150 first editions of this book and, with the help of genealogical websites, signatures, dates and locations, worked out who some of the owners were and what they did.

In the 1860s, Moby-Dick almost disappeared from the historical record, a situation not helped by a fire at his publisher’s works. But silence and absence are different things. There were many readers who still enjoyed Moby-Dick, though they only glancingly show up in print.

Moby-Dick’s early readers

My research has found that children read and lived with Moby-Dick in the 19th century. It pops up in memoirs, reminiscences, fictions and juvenile literature.

They played games based on the book; they took it out from libraries and made it dog-eared; they scrawled odd and eerie images on it; they and elder generations read it out loud together; and Moby-Dick (evidently a familiar character) himself featured in a Christmas tale about mermaids called The Merman and the Figure-Head (1871) by Clara Florida Guernsey.

If we take children as its audience, rather than scholarly readers, a quite different Moby-Dick appears. The novel’s plot becomes straightforward and exciting, its tone blithe and consumable, its function to teach and to entertain.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Other non-specialist readers sustained its reputation on similar terms. It seems very likely working-class sailor readers enjoyed it. That’s because its basic plot appears in a number of dime novels (mass-produced thriller fiction) such as Robert Starbuck’s The Mad Skipper (1866) and Captain Barnacle’s Péhe Nu-é (1877), written by and for such readers.

It also, sporadically, appears on deck, with one sailor, the future sea fiction writer Louis Becke, learning of it in Apia in the Samoan islands via “a small and sweet-natured English lady” who came on board with it and read it aloud with the captain. Becke recounts this episode in an introduction to Moby-Dick in a reissue of 1901.

As time went, on these foundational readers found extra fellow enthusiasts among socialists, queer people, outcasts and travellers, even if things continued much as they always had done. Literature professor Hershel Parker’s “historical note” to the Northwestern-Newberry edition tracks some of these readers down.

In the early decades of the 20th century, Moby-Dick moved up in the world. But, generally, even if it cultivated a bourgeois reading audience, it did so as a perfect example of the historically remote form of the sea romance, rather than as a classic.

The major event in Moby-Dick’s reputation in the 1920s was a popular silent film adaptation, The Sea Beast (1926). Collectively, readers thought of it less in analytical terms, than as something that offered guidance on how to live. I have found hundreds of off-hand, ordinary (and moving for that fact) references to it in travel narratives, letters, diaries, novels, poems and anecdotes from this era.

Making visible these early readers who viewed Moby-Dick as mass cultural genre fiction creates a picture of a substantially different novel. It ceases to rise, Everest-like and admonitory, amid the peaks of the canon. Instead, it descends from the heights to subsist, amiably and openly, in the ardours and passions of the everyday.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Edward Sugden’s suggestion:

I often wonder “what is the Moby-Dick of the 20th century?” I would nominate Gene Wolfe’s science fiction masterpiece, The Fifth Head of Cerberus novellas (1972). The novelist Ursula Le Guin once called Wolfe “our Melville”, so I’m in good company.

The three novellas are set on the fictional planets Sainte Croix and Sainte Anne. They are about the relationship between (possibly) human settlers and a (possibly) shape-shifting indigenous population who may or may not have existed.

In a dense, cryptic, visionary, philosophical and astonishingly crisp style, these novellas explore cloning, evil, dreamworlds, alien life, identity, fate, ritual, ethnology and much more besides in ways that defy summary and which far exceed any plot synopsis. It feels – in spirit and in terms of its reception – something like Moby-Dick.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Edward Sugden, King's College London

Read more:

- Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol is a work of art activism beloved by Banksy

- Mary Dorcey: queer Irish poet illuminates a form of sexuality even the law has overlooked

- The Coin by Palestinian writer Yasmin Zaher wins the Dylan Thomas Prize – an expert from the judging panel explains why

Edward Sugden does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation