Around one in ten Australians say they follow a gluten-free diet.

This means eliminating common foods – such as bread, pasta and noodles – that contain gluten, a protein found mainly in wheat, barley and rye.

Not everyone who follows a gluten-free diet has an underlying condition. But if you experience nausea, bloating or stomach pain after eating gluten, it could be the sign of a gluten intolerance, or coeliac disease.

While gluten intolerance and coeliac disease share many similar symptoms, one can cause intestinal damage and malnutrition. So, what’s the difference?

What is coeliac disease?

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune disease. This means the body mistakenly starts attacking healthy cells and tissue – in this case, in the small intestine – causing inflammation.

It affects around one in 70 Australians, but only 20% of this group are diagnosed.

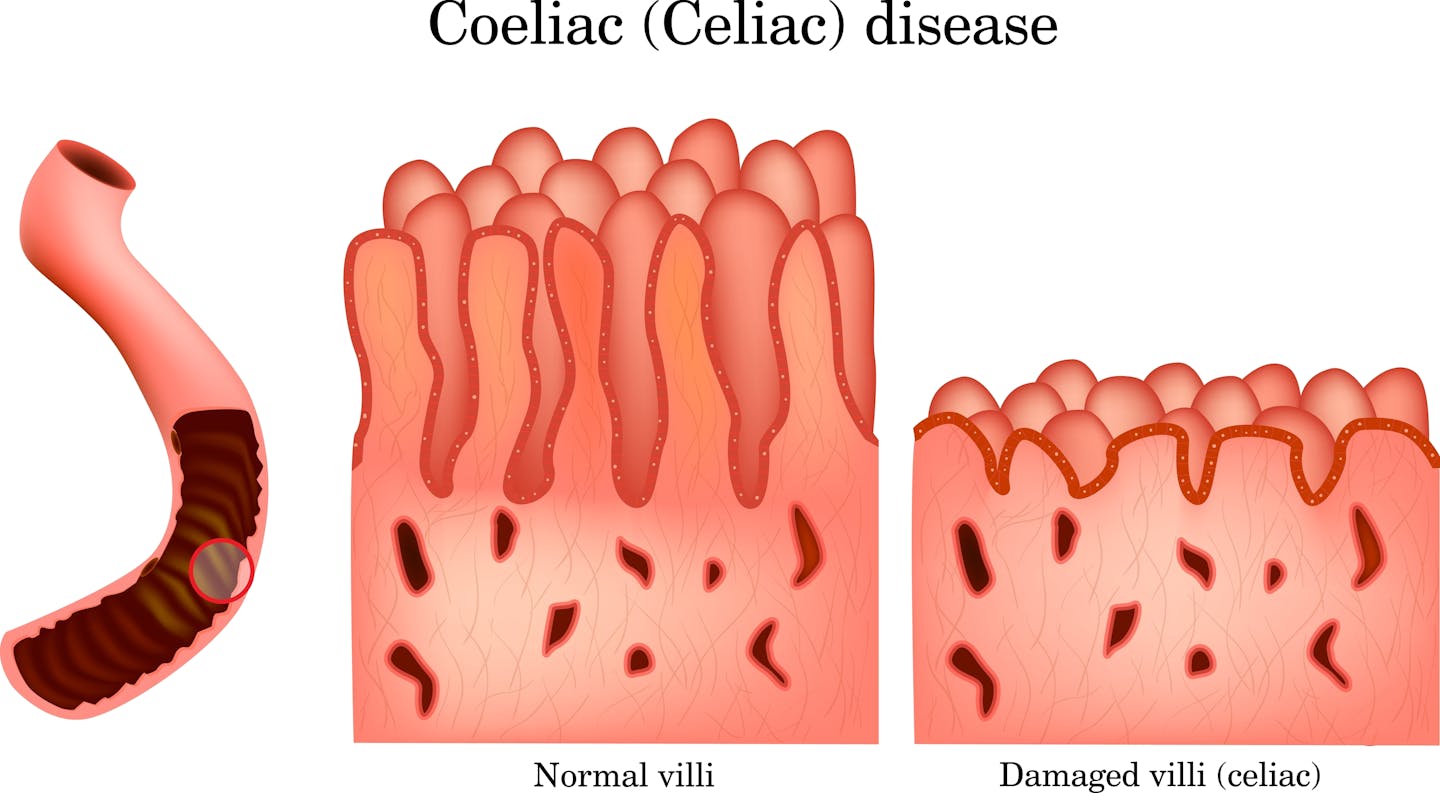

If you have coeliac disease, eating foods that contain gluten can damage your villi, structures in the small intestine that help the body absorb nutrients.

Following a meal containing gluten, you may experience digestive problems including diarrhoea, bloating, nausea, gas and abdominal pain.

Gluten can also cause non-digestive symptoms such as brain fog, headaches, dermatitis herpetiformis (an itchy, blistery skin rash), joint pain and fatigue.

In the long term, untreated coeliac disease can lead to malnutrition because the damaged villi can’t absorb nutrients from food. It can also reduce bone mineral density and has been linked to neurological disorders such as epilepsy and dementia.

How is coeliac disease diagnosed?

For an accurate diagnosis, you must not have eliminated gluten from your diet yet. This is so its effect on your digestive system can be measured.

A diagnosis involves blood tests followed by biopsies of the small intestine using an endoscope (an instrument with a light that can look inside the body).

Blood tests look for antigens – markers of a reaction to gluten – while the biopsy inspects any damage to the villi in the intestine.

In some cases, a capsule endoscopy, where a pill-sized camera is swallowed, is used to look at the intestine and observe for damage.

What about gluten intolerance?

People with gluten intolerance experience similar symptoms to coeliac disease. The difference is, after consuming gluten, there is no autoimmune response or intestinal damage.

Gluten intolerance is sometimes known as non-coeliac gluten sensitivity.

An estimated 1% of Australians live with a gluten intolerance, but only 12 in every 100 of this group are diagnosed by a doctor.

Doctors will rule out coeliac disease and wheat allergies as a first step for a person with symptoms related to eating gluten.

Once these have been ruled out, a gluten-free diet trial, supervised by an accredited practising dietitian, might be recommended to see if symptoms improve.

A formal diagnosis of gluten intolerance can only be confirmed using a highly complex dietary trial that compares the effect of gluten and a placebo over at least eight weeks.

This form of scientific study is very labour-intensive and not very common.

So instead many people just choose to eliminate gluten, without a diagnosis.

Extreme sensitivity to gluten

Coeliac disease is more severe than gluten intolerance and sensitivity can vary among those diagnosed.

Even traces of gluten can trigger symptoms. This means a strict, lifelong, gluten-free diet essential.

It also means people with coeliac disease have to be careful about cross-contamination. For example, using the same knife, chopping board or toaster to cut or toast gluten-free bread and regular bread can transfer gluten particles and cause a reaction.

According to the latest studies, consuming just 50mg of gluten per day is enough to cause intestinal damage for people with coeliac disease.

For context, a slice of whole-wheat bread contains about 4,800mg of gluten, meaning 50mg is around 1/100th of a slice of bread.

A small amount of gluten won’t affect someone with gluten intolerance in the same way. They may have temporary symptoms, but won’t experience intestinal damage.

However, the symptoms and their severity can vary from person to person, depending on their individual sensitivity.

Read more: What's the difference between a food allergy and an intolerance?

Should I cut out gluten, just in case?

You might be wondering if there is a downside to avoiding gluten, if you don’t have coeliac disease or an intolerance.

There can be.

Grain foods that contain gluten are rich in essential nutrients such as fibre, folate, iron and B-group vitamins.

Avoiding gluten when you don’t need to can lead to nutritional deficiencies.

Gluten-free products can also be more expensive and are sometimes higher in sugar, salt and fat to help compensate for texture and taste.

Before making any changes to your diet, it is best to speak with an accredited practising dietitian to make sure you’re not missing out on important nutrients.

So, what if you have symptoms?

Common signs of a gluten intolerance or coeliac disease include bloating, diarrhoea or constipation, and stomach pain. Both conditions can trigger non-gastrointestinal symptoms such as headaches, fatigue and joint pain.

If these symptoms sound familiar, it’s best to speak to a health-care professional who may test you for coeliac disease and/or a wheat allergy before eliminating gluten from your diet.

Remember, self-diagnosing and removing gluten without proper guidance might do you more harm than good.

If your symptoms concern you, speak to your GP, a gastroenterologist or a qualified dietitian. Dietitians Australia has a list of accredited practising dietitians.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Yasmine Probst, University of Wollongong and Olivia Wills, University of Wollongong

Read more:

- People with severe mental illness are waiting for days in hospital EDs. Here’s how we can do better

- Why do some people need less sleep than others? A gene variation could have something to do with it

- Is the private hospital system collapsing? Here’s what the sector’s financial instability means for you

Yasmine Probst receives funding from Multiple Sclerosis Australia.

Olivia Wills does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Wrap Movies

The Wrap Movies Washington Examiner

Washington Examiner  Aljazeera US & Canada

Aljazeera US & Canada New York Post

New York Post