The protagonist in Raaza Jamshed’s novel What Kept You? grows up in Lahore, Pakistan, under her grandmother’s watchful eye, in a house that sits in the shadow of the city’s walls. The memory of the turmoil and human suffering that resulted from India’s Partition in 1947 swirls around Jahan’s upbringing.

In an attempt to make her fearful of what awaits her outside the relative safety of home, Jahan’s female carers tell her stories about demons, as well as the more mundane reality of men’s violence against women and bodies turning up on the street.

Both of these threads, the mythic and the mundane, are ways of storying the pall of fear cast by violence and its memory. A refrain repeated throughout the novel – that “these are not our stories” – hints that Jahan is searching for an alternative story for herself.

This desire motivates her to migrate to Sydney, and brings about the novel’s key events: meeting her partner Ali, moving together to live on a property on Sydney’s western outskirts, suffering a miscarriage, and surviving a bushfire that provides both climactic drama and catharsis.

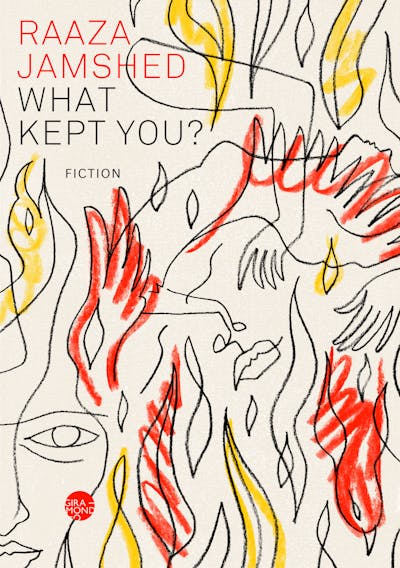

Review: What Kept You? – Raaza Jamshed (Giramondo)

Like much modern fiction, it is clear that What Kept You? is loosely drawn from the author’s life. Jamshed is herself a migrant writer who, like her protagonist, is from Pakistan, with Muslim ancestors who migrated from Kashmir. Like her protagonist, she lives in Western Sydney and teaches there. She and her partner, like Jahan and Ali, have divergent backgrounds, with the commonality that they are both Muslim. And like Jahan and Ali, she and her partner have moved to the semi-rural edges of the city.

The genre of migrant autofiction, especially coming-of-age work, is blooming, but Jamshed’s book stands out. Although this is her debut novel, her voice is mature. The narration moves between the protagonist’s youth and her adulthood, but its concerns are squarely adult. Indeed, they are the kinds of concerns that adults around me are perennially experiencing – namely, questions about what we owe to generations before and after us, to our (grand)parents and our children.

What Kept You? is not a plot-driven novel. Instead, it derives its propulsion from its powerful feminist sensibility, which inflects Jamshed’s thematic, structural and stylistic choices.

Jamshed uses Jahan’s childhood home in Lahore, which is surrounded by walls, to offer a political commentary on the false security offered by borders. As feminist scholars of security have long noted, what keeps a nation secure is not the same as what keeps its people secure. Instruments like hard borders and walls generate the theatre of security and order from the point-of-view of the state, but they do not generate true, felt, individual safety.

Feminist peace scholars argue this too: forms of violence, such as gendered violence, persist long after the final peace agreement is signed. They suggest that a more comprehensive look at peace would also consider everyday experiences, especially the experiences of marginalised groups, in order to fully grasp what peace is.

Jamshed answers this call, giving a feminist account of peace through the medium of literature. She accomplishes this by focusing on the local and the affective: her writing sits with the ordinary daily life of individuals, girls and women. It registers the feelings that life in this city during this time brings up for them. Jahan, like other female characters in What Kept You?, is not made safe within the climate of fear. She frequently describes feeling stifled, suffocated and claustrophobic – sometimes literally choking on rancid air.

Home and departure

The novel’s discussions of home and departure are refreshing because Jahan is a woman who occupies the role of the hero, journeying out into the world in search of freedom. Her departure from Lahore is a knowing attempt not only to cast off the constraining expectations of her grandmother and mother, but the suffocation of their stories.

In the novel’s closing scene, Jahan swims in a river with a horse she has stayed back to protect from a bushfire. The symbolic meaning is evident: both she and the horse are unbridled. She concludes: “here, in this moment, I am in my own [story]”.

Running alongside these triumphant and liberating moments are sombre meditations on the consequences of being a “woman who has left home”. Jahan, having left Lahore under contentious circumstances, has a strained relationship with her grandmother. When her grandmother passes, she does not return to Pakistan.

For a character whose sense of self – her story of who she is as a person – stems partially from matrilineal relationships, this rift unmoors her. The novel offers a complex account of gendered grief, as well as ambiguous grief. With few directions to channel her sadness over her grandmother, and after her miscarriage in Sydney, Jahan receives the advice to write a letter to seek closure.

In adopting a quasi-epistolary format and eschewing a linear style, Jamshed continues to execute her feminist project. The two losses – Jahan’s miscarriage and the passing of her grandmother – yield the novel’s ambitious structure. It is told chronologically, but with the chapters alternating between past and present. The most important and dramatic events – the miscarriage and bushfire – are loaded into the final third of the book.

What Kept You? also makes ample use of the sometimes unpopular second-person – an approach that allows the narrator to comment on her younger self at the same time as she remains within the novel’s action. These moments of action, which are told in the first-person and feature direct dialogue, achieve dramatic tension.

Jahan’s recollections of her relationships with two female characters, Aisha and Choti, carry significant weight in the middle sections of the novel. Although both relationships are shaped by events that circle around male characters, they offer a memorable exploration of female friendship and the possibilities for solidarity among women, especially across differences.

In one scene, Jahan kisses a male character, whom she dubs Some Boy. It is an unpleasant experience – and she is betrayed by Aisha. This coming-of-age moment, a first kiss, is made memorable because of Jamshed’s abilities as a feminist storyteller. “I shoved him away,” Jahan recounts, “certain now that I always could have.” Some Boy is decentered and fades away, but the heartbreak Jahan experiences at the hands of Aisha lingers.

What Kept You? is full of ambitious sentences. Where the author’s experiments pay off, the writing is lyrical and invites the reader in, generating the intimacy that Jamshed is likely seeking, though not every experiment succeeds. Some turns of phrase create distance and opacity, or just awkwardness and distraction. Sentences like “his eyes glanced in my direction” or “I hear my mouth utter” read as disembodied, while expressions like “She had a fish face, a goldfish to be precise”, and “This was Ali; Ali was the stranger’s name” feel forced and searching.

Overall, the novel is notably and self-consciously interested in and serious about the use of language, which is appropriate given that Jamshed is a multilingual writer interested in the politics of language. The tongues Jahan navigates – English, Urdu, Punjabi and Arabic – generate slippages and incomplete meanings, and often amplify moments of estrangement that are common in diasporic writing.

That some of the prose reads as exaggerated is to be expected, given Jamshed’s ambition to produce work that is sweeping and mythic, including in its deployment of language, and her intentions to handle it with reverence. Jamshed approaches language as ballast – heavy, weighty with history, and substantial. In so doing, she frequently succeeds at letting fly something that lands with an epic bang.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Eda Gunaydin, University of Wollongong

Read more:

- How can the International Criminal Court achieve justice for women?

- Friday essay: what can we learn about a city from its writers?

- Clones and superfans: 28 years on, our feelings about Diana reflect who we are

Eda Gunaydin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

FOX News Videos

FOX News Videos 5 On Your Side Sports

5 On Your Side Sports The US Sun Entertainment

The US Sun Entertainment CNN Video

CNN Video Raw Story

Raw Story ESPN Cricket Headlines

ESPN Cricket Headlines RadarOnline

RadarOnline