In the United States, around 1% of abortions occur after 21 weeks. Yet these abortions are intensely vilified. Recall Donald Trump’s graphic and false claim that US laws allowed doctors to “rip the baby out of the womb in the ninth month, on the final day”.

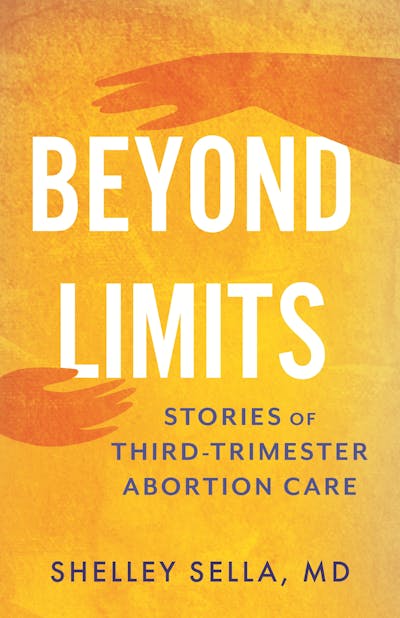

For two decades, Dr Shelley Sella provided abortion care in the US into the third trimester of pregnancy: that is, after 26 weeks gestation. Her new book Beyond Limits offers an intimate account of health care and politics, written from the front lines of America’s abortion wars.

Review: Beyond Limits: Stories of Third-Trimester Abortion Care – Shelley Sella, MD (Random House)

In Australia, abortion after 20 weeks gestation is also statistically rare – and most Australians agree that people need abortions after 20 weeks for a variety of medical and social reasons. However, in the last year or so, the focus on later abortions seems to be intensifying here, along with misinformation.

Every Australian jurisdiction but the ACT has a legal gestation limit (ranging from 16 to 24 weeks), after which two doctors must agree the abortion is necessary.

Yet a common claim made by abortion opponents like Tony Abbott and Barnaby Joyce is that Australia’s laws allow abortion “for any reason” “right up to the time of birth”.

Last year, the SA parliament narrowly voted down a so-called forced birth bill that would have banned abortion from 28 weeks. Simultaneously, during the Queensland state election, MP Robbie Katter boasted he would table legislation aiming to reduce the state’s gestation limit to 16 weeks or even a “clean repeal” of decriminalisation.

During this time, Senator Jacinta Price insisted abortion after the first trimester was “late term” – and called for abortion to be on the national agenda.

“Late-term abortion”, neither a medical or clinical term, has been a touchstone for US anti-abortion activism and lobbying. That rhetoric frequently dominates how this procedure is discussed – and not just in the US.

Humanising the issue

Sella’s book is part memoir, part activism – and at its core is the fundamental belief that empathy and understanding can overcome stigma and stereotype.

She aims to humanise the complicated, often desperate circumstances that mean people need abortion care later in pregnancy. She argues the procedure is “never, ever a casual decision”.

Quoting the mother of a young rape victim, Sella reminds us: “You don’t know the story until you are the story.”

Sella was born in New York City in the mid-1950s, the daughter of two Israeli immigrants in an “unhappy household”.

From the ages of 12 to 15, she writes, she was sexually abused. When Sella was 14, she missed her period for several months. She remembers, “I absolutely knew I would kill myself if I were pregnant.” Although she managed to find a community clinic and learned she was not pregnant, this visit, including a painful pelvic exam, compounded her feelings of shame, fear and isolation.

Throughout the book, Sella returns to these experiences in her early teens, framing them as underpinning her approach to health care and interest in abortion. Her goal was always “to treat patients as I would have wished to have been treated as an abused, frightened girl – that is, with understanding, an open heart, and compassion”.

Sella first encountered abortion in her early twenties through her involvement in second-wave feminism and the women’s health care movement. She trained and briefly worked as a midwife before becoming an OB-GYN.

In her early 40s, feeling professionally unfulfilled, Sella decided to focus on abortion provision. Her life was then transformed by a chance conversation about abortion and midwifery with Dr George Tiller, the owner of a Kansas clinic that was one of three in the country that provided third-trimester abortions.

Superficially, they were an unlikely pair. Sella was an “obstinate” Jewish lesbian and Tiller was “prickly”, “deeply patriotic” and a devout Lutheran. But they developed a profound rapport – he became both mentor and like a “second father”.

Tiller’s oft-repeated motto was “trust women”. When training Sella, he emphasised the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of later abortion patients.

Dismantling stereotypes, fighting stigma

Later gestation abortions occur after a significant adverse medical diagnosis, or because of the complex and often traumatic circumstances of the woman or pregnant person. Sella believes patient stories are vital in helping people understand the importance of both this type of care and access to abortion more broadly.

Drawing from her diary to offer vivid composite portraits of patients, Sella explores the nuances of why people seek a third-trimester abortion.

In Part 1, she alternates between chapters that tell her own story alongside a “working week” in New Mexico, tracing the stories, emotions and experiences of six women. She introduces the reader to the multi-day nature of a third-trimester abortion and explores the centrality of patient-centred care.

Sella also charts the immense logistical and financial barriers patients overcome to access these abortions. Roe v Wade (overturned in 2022) found abortion to be a constitutional right until viability, the point in pregnancy at which a fetus can theoretically survive outside the womb. The majority of US states banned abortion after 24 weeks and most of Sella’s third-trimester patients travelled far from home to access care.

Read more: How abortion laws focusing on fetal viability miss the mark on women's experiences

Mary and Christopher, Jamie and Robert, and Amrita and Arun are “fetal indication” patients, terminating wanted pregnancies after serious fetal anomaly diagnoses, such as lissencephaly (also known as smooth brain), a rare but severe congenital condition.

Mary and Christopher’s story is particularly striking. Catholics who oppose abortion, they chose to terminate their pregnancy because “as long or as short as their child’s life might be, they did not want their child to suffer”. Their faith and politics meant they felt completely alone, in contrast to the other couples chronicled in the book, who have church, community and family support.

Laura, Irene, and Noor are “maternal indication” patients, accessing abortion because of their life circumstances.

Laura, a mother of four, was experiencing extreme domestic violence and had cancelled several earlier abortion appointments. Irene is a single mother whose pregnancy symptoms were masked by the return of her stomach cancer. She couldn’t begin chemotherapy while pregnant and was terrified she would die before her daughter finished high school.

Noor, the 17-year-old daughter of Iranian immigrants, was unable to access abortion care because of state parental consent laws for minors. She believed her parents would disown her for having sex before marriage, yet when they eventually learned she was pregnant they supported her desire for an abortion. Her father accompanied her for the week.

In the shorter Part 2, Sella addresses common assumptions about third-trimester abortion, including questions like “why did she wait so long?” and “why doesn’t she just give the baby up for adoption?”

The book is filled with emotionally devastating stories. Sella reminds us “patients make their decisions based on the reality of their lives, not the fantasy version”. Throughout, Sella’s central theme is that if we are willing to sit and really take in other people’s experiences, they “should inspire compassion rather than judgement”.

But Sella also asks the reader to view third-trimester abortion as health care that empowers, rather than simply as tragedy. She writes about the purpose and motivation that inspired and sustained her:

I fully embraced my patients’ hopes, dreams, and aspirations for themselves and their families. I was proud to be able to provide them with care that could make that possible.

Politics and abortion

Even as Sella’s memoir honours and humanises the patients she has cared for and the people she has worked with, it is also a narrative of the intense impact of anti-abortion activism in the US.

Tiller experienced extreme, violent harassment by opponents of abortion. In 2009, he was murdered in his church while attending Sunday services. Sella writes about this tragedy with spare, deeply moving prose.

Sella and a colleague resolved to continue offering care, eventually establishing a third-trimester service in New Mexico. They, along with the other two doctors who openly performed third-trimester abortions in the US, agreed to be filmed in the award-winning documentary After Tiller.

Beyond Limits also charts the broader impact of anti-abortion activism on people seeking care. Sella writes with grace about the way right-to-life rhetoric shapes the emotions and fears of her patients.

The book chronicles the impact of events outside New Mexico. In the 2010s, there were mass clinic closures after anti-choice states passed laws targeting abortion providers. At the start of COVID, some states closed clinics because abortion was “not medically necessary”.

Writing in the epilogue about the overturning of Roe v Wade in 2022 and the end of the constitutional right to abortion, Sella argues the effect has been

to extend the difficulties and challenges that so many of my third-trimester patients always faced to all women in states that now have free rein to limit or ban abortion.

As Australian anti-abortion politicians and activists increase their vilification of later gestation abortion and the people who access this care, we would do well to heed Sella’s message of compassion and empathy and resist the politicisation of healthcare.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Prudence Flowers, Flinders University

Read more:

- Women’s rights in the US are in real danger of going back to 1965 – so Jessie Murph’s new song is no laughing matter

- UN climate chief tells Australia to ‘go big’ with its 2035 emissions reduction target

- Barnaby Joyce wants Australia to abandon net zero – but his 4 central claims don’t stack up

Prudence Flowers has received funding from the South Australian Department of Human Services. She is a member of the South Australian Abortion Action Coalition.

The Conversation

The Conversation

ABC News

ABC News Local News in California

Local News in California Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News Local News in New York

Local News in New York Local News in Washington

Local News in Washington Reuters US Business

Reuters US Business Raw Story

Raw Story The Week

The Week Daily Kos

Daily Kos FOX News Videos

FOX News Videos