Last month, courts on both sides of the Atlantic delivered a clear verdict: when classifying titanium dioxide as carcinogenic, regulatory agencies had overreached.

These parallel legal defeats expose deeper questions about who gets to interpret contested science.

In the modern world, legal decisions – especially ones dealing with regulation – are increasingly based on complex science. But sometimes, the science isn’t settled. When certainty remains elusive, who gets to be the authority?

The case of titanium dioxide

Titanium dioxide lies at the heart of the recent legal challenges. It’s a white mineral powder used in many everyday products such as paint, sunscreen, toothpaste and even food.

For decades, titanium dioxide was considered safe. However, in the early 2000s, with the advent of nanomaterials science, it became widely available in nanoparticle form. And scientists found that typical titanium dioxide powder contains some nanoparticles too.

Research emerged showing these tiny titanium dioxide particles may interact with biological systems differently compared with their larger counterparts. This sparked controversy about a substance previously thought to be safe.

The turning point came in 2010, when the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified titanium dioxide as “possibly carcinogenic to humans”. This means there’s limited evidence for human carcinogenicity, but there could be some evidence from animal studies, or simply evidence that the substance has the characteristics of a carcinogen.

In the case of titanium dioxide, the classification was primarily based on studies in rats. The animals had more lung tumours when they breathed in high concentrations of titanium dioxide particles.

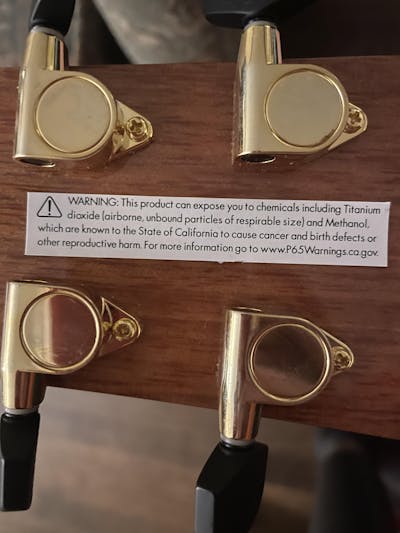

Naturally, regulators responded. California added airborne titanium dioxide of certain particle sizes to its Proposition 65 list in 2011. This meant products with it, such as spray-on sunscreens and cosmetic powders, would need warning labels.

Eight years later, the European Commission also classified titanium dioxide powder as a suspected carcinogen. This resulted in mandatory warning labels on products with titanium dioxide powder sold in Europe.

Decisive – or not so much?

A warning label might seem decisive. However, beneath it lies a profound scientific uncertainty. It’s a common challenge with emerging fields such as nanoscience.

For titanium dioxide, the uncertainty manifested in two ways.

First, as with many suspected carcinogens, the IARC classification ignited debate within the scientific community. Could animal study results meaningfully predict human cancer risk? Animal studies often demonstrate a strong mechanism for harm, but it’s not possible to test directly in humans. That makes it tricky to establish cause and effect.

Read more: If 'correlation doesn’t imply causation', how do scientists figure out why things happen?

Second, studies on nano titanium dioxide toxicity continue to yield inconsistent and contradictory findings. Current research shows toxicity heavily depends on several factors, from exposure to individual susceptibility.

Evidence in the courts

The scientific complexity on titanium dioxide created fertile ground for legal challenges. Industry groups contested both “carcinogenic” rulings, arguing regulators had misinterpreted the science.

The courts ultimately agreed. On August 1 2025, Europe’s highest court sided with the titanium dioxide industry. It found European regulators had failed to consider all relevant factors when assessing scientific evidence.

This ruling hinged on something highly technical. The courts found regulators had used an incorrect particle density value when calculating lung overload in rat studies. This undermined their assessment of whether the animal data reliably predicted human cancer risk. The court nullified the classification entirely.

Similarly, on August 12 2025, a US federal court struck down warning requirements for titanium dioxide in cosmetics.

While acknowledging the warnings were technically accurate sentence-by-sentence, the court found the underlying science didn’t meet the established legal standard of being “purely factual and uncontroversial”.

In part, the warnings were deemed “controversial” because significant scientific debate persists.

The legal landscape is changing

These court rulings represent a critical evolution in regulatory science.

In their initial classification decisions, the US and European agencies prioritised precaution. They recognised that animal studies typically come before human evidence, and that research on nano titanium dioxide was still emerging.

They followed the proper established processes and made reasonable decisions under uncertainty.

In both cases, the courts used legal knowledge standards to reject these scientific applications. This blurs the boundary between science and how courts oversee regulatory processes.

Critics argue courts “are not scientists” and lack the expertise to make these types of decisions. Judges are trained for legal complexity and shouldn’t replace the decisions of trained scientific committees in areas of scientific uncertainty.

When courts and science intertwine

Rulings such as the ones on titanium dioxide raise several important questions for our legal system.

How much do judges really understand science? Should judges be able to override trained scientists to resolve technical disputes? Or does judicial oversight effectively balance against regulatory overreach in complex scientific contexts?

When should regulators act on complex science? Since the 1950s, many toxic substances present this dilemma: controlled human studies are unethical, and widespread exposure eliminates the unexposed control groups needed for comparison. Should agencies wait for definitive proof – which may not be possible to obtain – or act on evidence of potential harm to protect public health?

Can scientists effectively communicate uncertainty? Emerging science is in a constant state of uncertainty. By contrast, legal systems require definitive decisions within specific timeframes. When scientific consensus is lacking, how can scientists help regulators and courts proceed?

These questions aren’t just about interpreting science. As complex technologies continue to be integrated into our daily lives, scientific uncertainty could increasingly become a legal concern. How do we make sure our legal institutions are up to the task?

This is a big challenge, but one thing is clear: scientific and legal experts must work together to find the solution.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Sarah Wilson, University of Technology Sydney and Rachael Wakefield-Rann, University of Technology Sydney

Read more:

- Your immune system attacks drugs like it does viruses – paradoxically offering a way to improve cancer treatment

- From ‘reef-friendly’ sunscreens to ‘sustainable’ super, greenwashing allegations are rife. Here’s how the claims stack up

- Iron nanoparticles can help treat contaminated water – our team of scientists created them out of expired supplements

Rachael Wakefield-Rann receives research funding from various government and non-government organisations. She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would financially benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

Sarah Wilson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

New York Post Opinion

New York Post Opinion Raw Story

Raw Story RadarOnline

RadarOnline Daily Kos

Daily Kos CBS News

CBS News