Would you willingly have your legs broken, the bone stretched apart millimetre by millimetre and then spend months in recovery – all to be a few centimetres taller?

This the promise of limb-lengthening surgery. A procedure once reserved for correcting severe orthopaedic problems, it has now become a cosmetic trend. While it might sound like a quick fix for those hoping to make themselves taller, the procedure is far from simple. Bones, muscles, nerves and joint all pay a heavy price – and the risks often outweigh the rewards.

Limb lengthening is not new. The procedure was pioneered in the 1950s by Soviet orthopaedic surgeon Gavriil Ilizarov, who developed a system to treat badly healed fractures and congenital limb deformities. His technique revolutionised reconstructive orthopaedics and remains the foundation of current practice today.

While the number of people undergoing cosmetic limb-lengthening surgery each year still remains relatively small, the procedure is growing in popularity. Specialist clinics in the US, Europe, India and South Korea report increasing demand – with procedures costing tens of thousands of pounds.

Reports suggest that in some private clinics, cosmetic cases of limb-lengthening surgery now outnumber medically necessary ones. This reflects a cultural shift, where people are willing to undergo a demanding, high-risk medical procedure to meet social ideals about height.

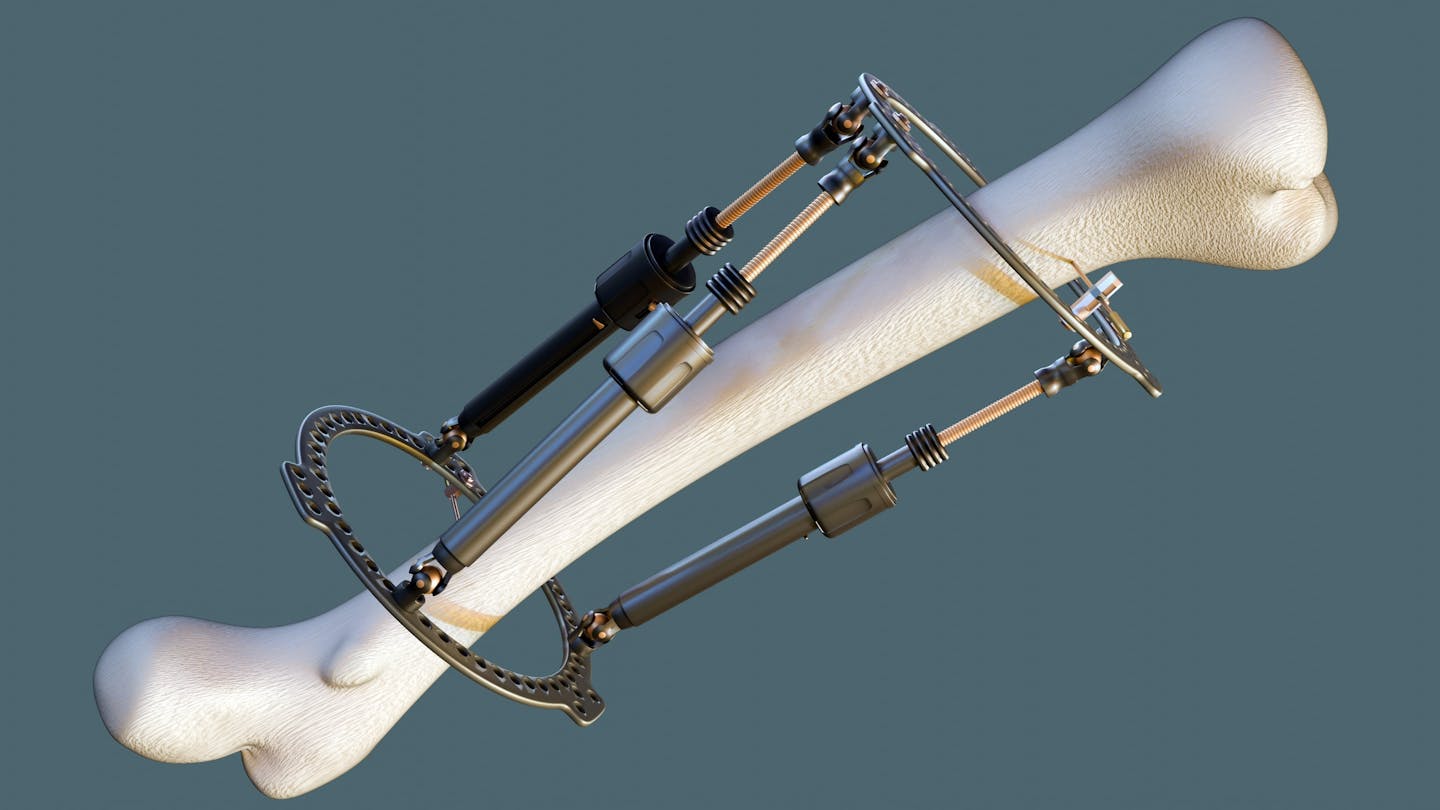

Surgeons begin by cutting through a bone – usually the femur (thigh bone) or tibia (shin bone). To ensure the existing bone stays healthy and that new bone can grow, surgeons are careful to leave intact its blood supply and periosteum (the soft issue that covers the bone).

Traditionally, the cut bone segments were then connected to a bulky external frame which was adjusted daily to pull the two ends apart. But more recently, some procedures have adopted telescopic rods placed inside of the bone itself.

These devices can be lengthened gradually using magnetic controls from outside the body – sparing patients the stigma of an external frame and reducing the risk of infection. However, they’re not suitable for all patients – especially children – and are considerably more expensive than external systems.

Regardless of whether the device sits outside or within the bone, the process is the same. After a short healing period, the device is adjusted to separate the cut ends very gradually, usually by about one millimetre per day. This slow separation encourages the body to fill the gap with new bone – a process called osteogenesis. Meanwhile, the muscles, tendons, blood vessels, skin and nerves stretch to accommodate the change.

Over weeks and months this can add up to a gain of five to eight centimetres in height from a single procedure – the limit most surgeons consider safe. Some patients undergo operations on both the femur and tibia, aiming to gain as much as 12–15 centimetres in total. However, complication rates rise sharply with each centimetre of additional growth. Complications include joint stiffness, nerve irritation, delayed bone healing, infection and chronic pain.

Intense pain

The underlying challenge of limb-lengthening surgery is the same: the body must constantly repair a bone that is being pulled apart.

When a bone breaks, a blood clot rapidly forms around the fracture. Bone cells (ostoblasts) create a callus (soft cartilage) that stabilises the break. Over weeks, osteoblasts replace this cartilage with new bone that gradually remodels to restore strength and shape.

In limb-lengthening surgeries, however, the fracture is continuously pulled apart. This means the body’s repair process is constantly interrupted and redirected, generating a column of delicate new bone where hardening is delayed.

The process is intensely painful. Patients often require strong painkillers. Physiotherapy is also essential to maintain movement. Yet, even when the surgery succeeds, people may still be left with weakness, altered gait or chronic discomfort.

There’s also the psychological burden that comes alongside the procedure. Recovery can take a year or more – much of it spent with restricted mobility. Some patients report depression or regret, particularly if the modest gain in height does not deliver the hoped-for improvement in confidence.

Muscles and tendons are also forced to lengthen beyond their natural capacity, which can lead to stiffness. Nerves are especially vulnerable. Unlike bone, they cannot regenerate across long distances. Healthy nerves can stretch by perhaps 6–8% of their resting length – but beyond this, the fibres begin to suffer injury and become impaired.

Patients often experience tingling, numbness or burning pain during lengthening. In severe cases, nerve damage may be permanent. Joints, immobilised for months, are at risk of stiffening or developing arthritis because of changes to how force and weight are distributed.

The rise of cosmetic limb-lengthening illustrates a broader trend in aesthetic surgery – where increasingly invasive procedures are offered to people without medical need. In theory, almost anyone could gain a few centimetres of height. But in practice, it means months of broken bones, fragile new tissue, exhausting physiotherapy and the constant risk of complications.

For those with medical need, the benefits can be life-changing. But for those seeking only to add a little height, the question remains whether enduring months of pain and uncertainty is really worth it.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Michelle Spear, University of Bristol

Read more:

- From blood clots to rare cancers, a plastic surgeon explains the risks to consider before going under the knife – or the needle

- ‘I couldn’t stand the pain’: the Turkish holiday resort that’s become an emergency dental centre for Britons who can’t get treated at home

- Beauty ideals were as tough in the middle ages as they are now

Michelle Spear does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Raw Story

Raw Story Newsday

Newsday The US Sun Health

The US Sun Health Healthcare Dive

Healthcare Dive Cover Media

Cover Media Click2Houston

Click2Houston People Top Story

People Top Story KY3

KY3 Lansing State Journal

Lansing State Journal The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast