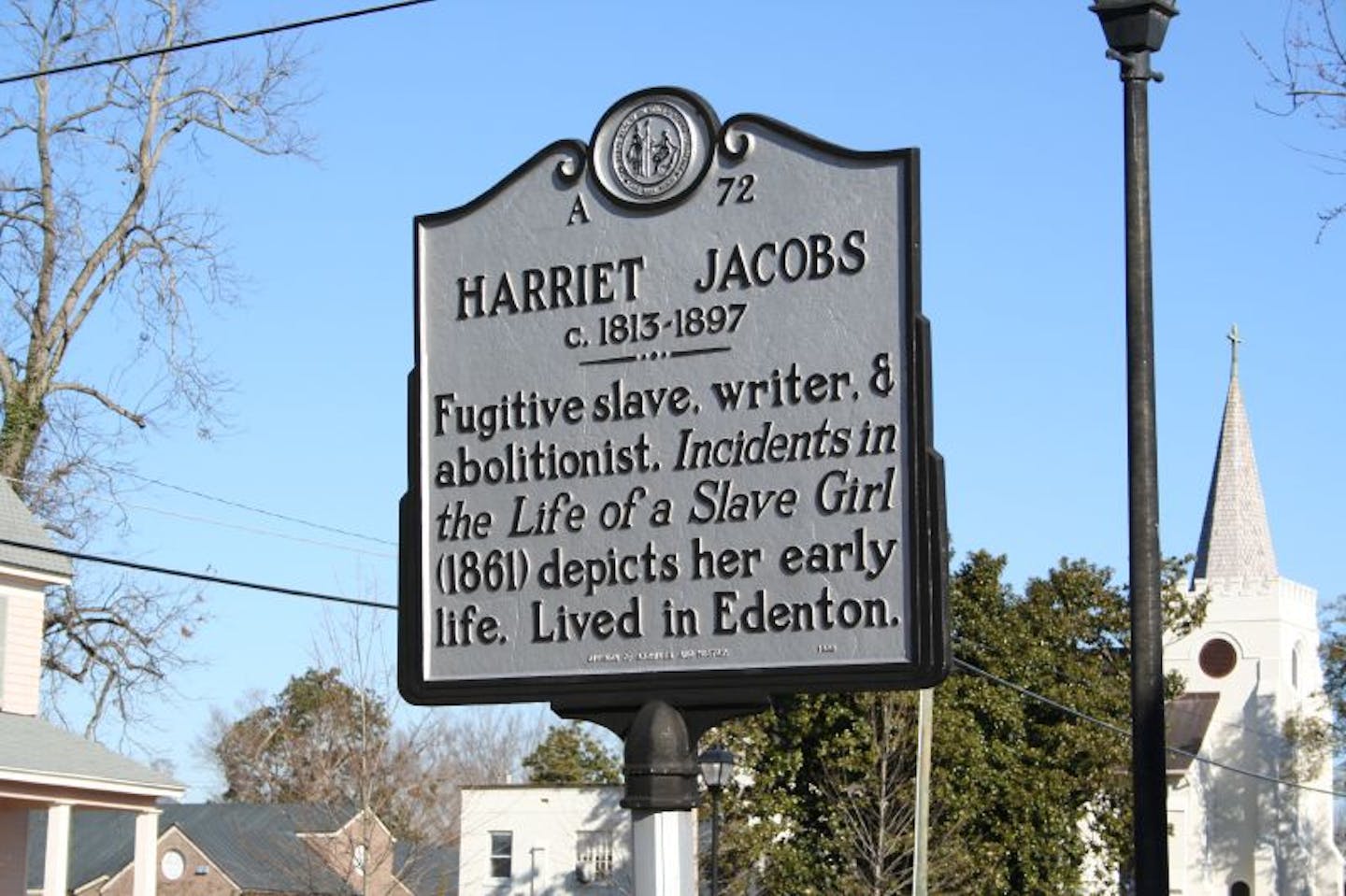

From the ages of 12 to about 22, Harriet Jacobs lived under the watch of her enslaver, a wealthy physician named James Norcom Sr. During that decade, as Jacobs grew from a child to a young woman, Norcom psychologically and physically terrorized her.

Once, when she was a teenager, he threw her down the stairs of his Edenton, North Carolina house. He swore it would never happen again. But as Jacobs later wrote, “I knew that he would forget his promise.”

Jacobs’ injuries took weeks to heal. Even after they did, she made sure nobody would forget what happened by including this harrowing moment in her 1861 autobiographical novel, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself,” one of the most important testimonies of captivity and survival ever written.

In July 2025, we stumbled across the staircase during a visit to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, an institution known for its preeminent collections of paintings, pottery, furniture and fine exhibits on Southern artisans and early American craft.

We’d gone there to see a table that belonged to a formerly enslaved writer named Samuel “Aleckson” Williams. But our attention was ultimately drawn several rooms away from the table, where we encountered woodwork – including the staircase Jacobs had written about – from the house where Norcom had enslaved her.

As scholars of 19th-century U.S. literature who regularly teach Jacobs’ “Incidents,” we were stunned to realize that the staircase had survived.

It caught us even more off guard because Jacobs’ life has been receiving a lot of attention from scholars. For decades, Jacobs’ book was read as a work of fiction, if it was even remembered at all. But in recent years, historians have recovered her papers and confirmed a number of biographical details. In 2024, a narrative written by her brother, John Jacobs, was republished.

For us, the experience highlighted the importance of these small, regional museums. The staircase hadn’t originally been salvaged due to its connection to Jacobs. But it had nonetheless been conserved and cared for, which allowed new meanings to slowly emerge.

A daring escape

In 1964, the Jacobs staircase – along with a door, a mantle and paneling – were taken from Norcom’s house in Edenton not because of their connection to Jacobs or her enslaver, but because of their significance to Revolutionary-era craftsmanship.

We weren’t the first to realize the staircase’s connection to Jacobs. Roughly 15 years ago, curator Robert Leath brought it to the attention of Anthony Parent, a history professor at Wake Forest University. Parent publicized the story of these material objects through local outreach and some scholarship.

But like many histories that emerge from unexpected places, the story of the staircase hasn’t gained much traction in broader conversations among Jacobs scholars, much less in popular memory and national history.

Across “Incidents,” Jacobs chronicles many moments of physical and psychological abuse. But the assault on the stairs stands out among the many acts of terror she endured.

“He had pitched me down stairs in a fit of passion,” she writes, “and the injury I received was so serious that I was unable to turn myself in bed for many days.”

Jacobs eventually fled her bondage and exchanged her life in captivity under Norcom for a life of quasi-freedom: She spent seven years hiding in a nearby attic. Eventually she made her way to the North, where she claimed her freedom and published her book.

Rediscovered in the 1970s, Jacobs’ story was so astonishing that some readers doubted its autobiographical accuracy. But historian Jean Yellin was able to verify many aspects of her narrative, including the fact that she had hidden in an attic for seven years.

Yellin’s revelations of Jacobs’ life and work – in addition to the harrowing experiences of other women held in captivity – helped change the way Americans have been able to learn about how women, both enslaved and free, survive coercion and sexual violence.

Hidden in plain sight

At the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, the staircase appears in between two separate galleries. On the wall along the steps to the first landing, a framed photograph of Harriet Jacobs and a framed copy of the first edition of “Incidents” hang. Though visitors are allowed to ascend the stairs, they don’t lead anywhere. In the next room are the mantel and wood paneling from the Norcom house.

The museum’s website doesn’t include a write-up of the Jacobs staircase, nor does it showcase an image of the impressive installation, although it’s cataloged with care – and, thanks in part to Parent’s advocacy, generations of students have visited the museum to see what survives of Jacobs’ house.

The museum staff recounted the story of the staircase to us in the course of a conversation about Williams. They, too, believe that the stories behind objects have a way of enduring, even as the importance and meaning of artifacts change over time.

Stories that unfold in surprising ways

The installation at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts demonstrates the power of regional museums to preserve artifacts whose stories unfold over generations – whose meaning may not rest on the reasons they are salvaged, purchased or preserved, and whose significance might seem to be an accident in hindsight. These stories matter, even – and especially – when they played a role in the most violent chapters in U.S. history.

Jacobs’ staircase was valuable when it was acquired; it was understood then as an example of fine 18th-century craftsmanship, and that’s a story worth preserving and learning. And yet its story now has more chapters that enrich the narrative.

As the Trump administration is reassessing “troubling” ideological content at the Smithsonian and elsewhere – slashing grants and budgets and even advocating for the removal or reconstruction of exhibits that tell difficult stories – we think it’s important to look anew at how museums preserve objects and the acts of survival they carry forward.

This isn’t a story of discovery and recovery. Instead, our experience simply demonstrates why museums, archives and libraries matter. These institutions require space to play the long game, in ways no one can anticipate, so they can continue doing what they do best: collect, preserve, document and curate.

In doing so, they allow stories like Jacobs’ to unfold in remarkable and utterly unforeseeable ways.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Susanna Ashton, Clemson University and Mollie Barnes

Read more:

- With its executive order targeting the Smithsonian, the Trump administration opens up a new front in the history wars

- In a Roman villa at the center of a nasty inheritance dispute, a Caravaggio masterpiece is hidden from the public

- Trump administration seeks to starve libraries and museums of funding by shuttering this little-known agency

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Tribune Chronicle Community

Tribune Chronicle Community FOX News Travel

FOX News Travel WBAY TV-2

WBAY TV-2 AlterNet

AlterNet Raw Story

Raw Story The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone 5 On Your Side Sports

5 On Your Side Sports New York Post

New York Post