When state institutions crumble under the weight of chaos, desperate governments sometimes turn to controversial solutions. In Haiti, where gang violence has transformed the capital, Port-au-Prince, into a war zone and left over 5,600 people dead in 2024 alone, the government has made a striking decision to hire a private army to restore order.

Haiti’s interim government signed a deal in March with Vectus Global, a firm founded by American private security contractor Erik Prince, that has seen mercenaries help battle the gangs. Vectus operatives have reportedly served as instructors to Haitian security forces, while also coordinating drone strikes against gang-controlled areas and criminal leaders.

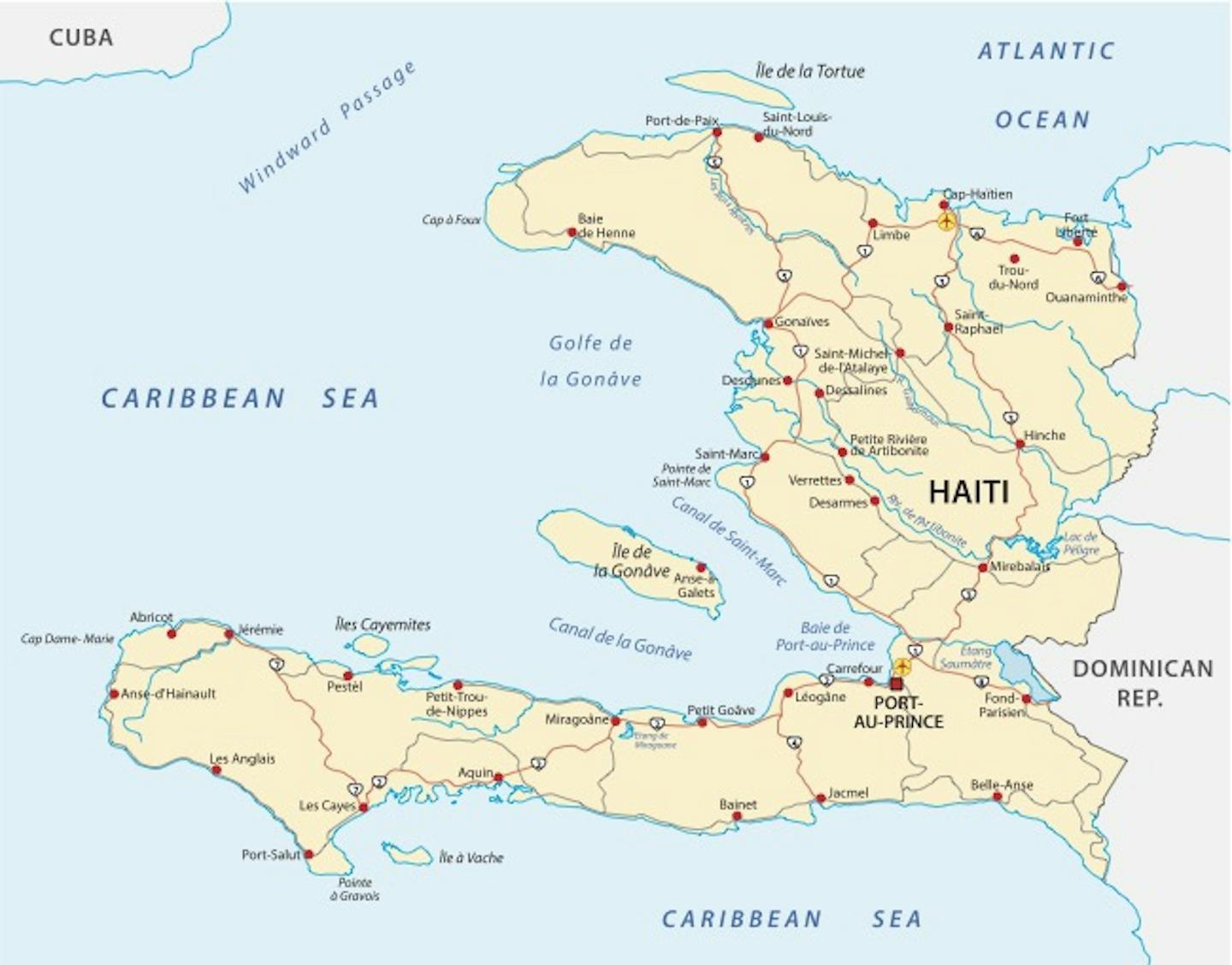

The firm is thought to have deployed nearly 200 personnel in Haiti, from the US, Europe and El Salvador. It plans to have stabilised major roads and pushed gangs out of their territory within about a year. In an interview with the Reuters news agency in August, Prince said the measure of success for him “will be when you can drive from Port-au-Prince to [the northern city of] Cap-Haïtien” without being stopped by gangs.

The arrangement, while having done little to curb the power of the gangs so far, represents a dramatic escalation in the privatisation of state security. It raises profound questions about sovereignty, accountability and the risks of ceding control of security to private military personnel.

Vectus Global is reportedly operating in Haiti under two parallel arrangements. The first involves a one-year contract in which Vectus staff will help Haiti restore order. Haiti’s government has not commented on the involvement of Vectus Global specifically, though it confirmed in June that it was using foreign contractors.

The second arrangement, which remains unconfirmed by the Haitian government, will supposedly see Prince’s firm play a role in restructuring Haiti’s customs and immigration services over a ten-year period. Haiti has long struggled to prevent gangs from exploiting its porous border with neighbouring Dominican Republic.

This move would represent an extraordinary transfer of sovereign functions. Reports indicate that Vectus Global will receive a performance-based commission of 20% of customs revenue increases in the first three years and 15% thereafter. It will also receive a fixed fee of 3% on import volumes regardless of performance.

Haiti’s security collapse provides context for such extreme solutions. Criminal groups now control 90% of Port-au-Prince and possess more firepower and manpower than national security forces. A Kenyan-led multinational security support mission was deployed to Haiti in 2024, but it remains understaffed and underfunded with only 1,000 of the 2,500 personnel envisioned initially.

And despite the assistance now being provided by private security personnel, the gangs have continued to expand their reach in the provinces. At least 1,520 people were killed and 600 were injured between April and the end of June across the country. The UN says more than 60% of these killings and injuries occurred during operations by security forces against the gangs.

Criminal groups united under the “Viv Ansanm” coalition continue to dictate events, maintain control over major areas of the capital and launch attacks in a bid to control more territory. There has been no significant territorial loss by gangs in recent months and essential supply chains, trade routes and public safety remain heavily disrupted.

A complex set of factors make combating gang violence in Haiti extremely difficult. Gangs have deep-rooted relationships with certain factions in local police and government, making it hard for external security personnel to dismantle their operations. At the same time, gang control of critical transport infrastructure has crippled tax collection, trade, access to medical supplies and food distribution.

Raising the alarm

Prominent NGOs and rights groups have strongly opposed Vectus Global’s involvement in Haiti. The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre flagged that Prince’s reported ten-year contract would put crucial state powers – including tax collection and deportation – under a private company’s control.

It warned of “serious concerns for human rights and government accountability”. This is because international legal guidelines for private military companies are largely non-binding, and tend to rely on voluntary codes of conduct.

Speaking to the media in August on the condition of anonymity, a senior White House official clarified that there is “no American involvement in hiring Vectus Global and no oversight” of its mission in Haiti. This has only raised further doubts as to who, if anyone, will hold private military personnel there accountable.

The dangers of privatised warfare are well documented. Prince’s own former company, Blackwater, faced numerous scandals over its conduct during the Iraq war. Blackwater provided security for US officials and military installations there.

In 2007, four Blackwater employees killed 17 Iraqi civilians and wounded 20 others in the Nisour Square massacre in Baghdad. While FBI investigations determined that at least 14 deaths were unjustified, all four convicted Blackwater contractors were pardoned by Donald Trump in 2020.

Vectus Global has communicated its plans in Haiti and operational adjustments. But fundamental criticisms relating to accountability, sustainability and lack of local institution-building remain largely unaddressed in public statements.

The deepening crisis in Haiti was on the agenda at the UN General Assembly in New York, where world leaders gathered in September for the 80th anniversary of the UN. The US pushed for a rebranding of the current multinational security support mission into a more aggressive “gang suppression force”, which has now been approved by the UN security council.

This force will have a new mandate, greater numbers and expanded autonomy from the Haitian police. Yet uncertainties remain over where the 5,500 people for the new force will come from, and who is going to pay.

As Haiti continues to struggle with rampant violence, Prince’s private army reflects governmental desperation rather than strategic wisdom. It is a model that prioritises private profit over public accountability and sustainable peace. The consequences are likely to shape how the world responds to state failure as traditional peacekeeping comes under pressure.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Nicolas Forsans, University of Essex

Read more:

- How Haiti became a failed state

- UN extends Kenyan policing mission in Haiti in futile attempt to tackle gangs

- Haiti’s gangs turn to starving children to bolster their ranks

Nicolas Forsans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in Arkansas

Local News in Arkansas CBS News

CBS News America News

America News Law & Crime

Law & Crime MENZMAG

MENZMAG WFIN News

WFIN News The Times of Northwest Indiana Crime

The Times of Northwest Indiana Crime AlterNet

AlterNet Orlando Sentinel Politics

Orlando Sentinel Politics