As we approach the headstone of Peter Jackson’s grave, we glimpse a flash of red at its base. Getting closer, we see that it’s a pair of boxing gloves. They are brand-new Fila gloves that retail for around A$80, so someone has spent a bit of money.

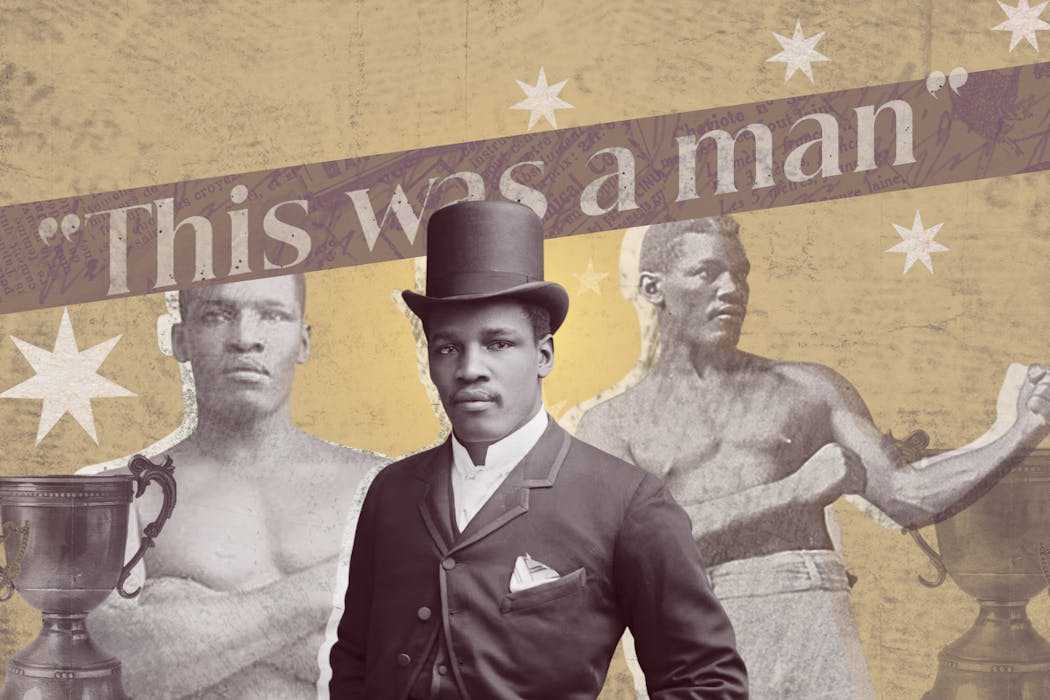

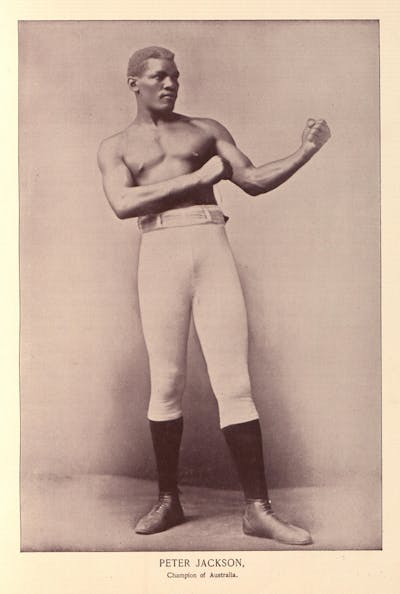

The gloves pay tribute to the late 19th-century Australian boxing champion and have been placed just below an inscription taken from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra: “This was a man.” Above the inscription is a white marble bust of Jackson. One might expect a depiction of him with arms aloft, victorious in the ring. Instead, he is in a three-piece suit. The image was likely modelled on a calling card he had made in London in 1895.

The ten-tonne monument’s grandiosity, the Shakespeare quote, the marble, all project universality. Peter Jackson, the Black Australian boxer born on the tiny Caribbean island of St Croix (now part of the US Virgin Islands) is rendered as a metonym for humanity.

The three-piece suit also reminds us of that other grand universal: the Victorian gentleman.

The most famous living Australian

I’ve come to Toowong cemetery in Brisbane with the Jamaican writer Sienna Brown. We’re in the midst of recording a podcast series about Caribbean Australians, focusing on arrivals in the second half of the 19th century.

We have previously explored in depth the history of Caribbean convicts, many of whom went directly from bondage to carceral banishment. From the 1850s, as the Caribbean sugar industry declined and the gold rushes drew fortune-seekers from around the world, a cohort of free Black West Indians started to make their way to the Australian colonies.

None looms larger than Jackson. He arrived in Australia at the age of 18 in 1879. At his peak in the early 1890s, he was easily the most famous living Australian in the world. When a collection was made to fund his headstone, its benefactors believed they were erecting a tourist attraction. One of Jackson’s successors as Australian heavyweight champion remarked in 1922 that “the grave of Peter Jackson is and ever will be one of the sights of Queensland”.

But how many have heard of him now? Clearly some – look at those bright red gloves – but he sits in a different category to Donald Bradman, Andrew Charlton, Dawn Fraser, Betty Cuthbert, and other early sporting champions who have been woven and rewoven into the stories we tell ourselves about sport, history, and Australian identity. Take, for instance, the attention Gideon Haigh lavishes on a single photo of one of Jackson’s near contemporaries, the cricketer Victor Trumper.

As we’ll come to, Jackson was a more significant figure, both in his sport and for the history of visual culture.

Circling the headstone in the dappled light of a late summer’s afternoon, a comment made by another Caribbean man 50 years after Jackson’s death occurs to us. In the opening pages of Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon, who was from Martinique to the south of Jackson’s St Croix, writes “the black man is not a man”.

In a world shaped by European colonialism, “man”, Fanon’s irony alerts us, is really a metonym of “white man”. It’s an insight that would give birth to the critical study of whiteness and, more broadly, critical race theory.

Is Jackson’s absence from Australia’s collective consciousness a sign of white universalism’s persistence? Is it a sign that, despite the efforts of theorists and activists and after decades of liberal discourse about Australia as a “successful multicultural society”, we are still not comfortable with a figure like Jackson exemplifying Australian success? That any insistence that he does would be regarded as a “woke” rewriting of history and identity?

What this line of questioning obscures is that Jackson was already an Australian icon in his time. Unlike many other successful Australians of colour, he doesn’t need to be recovered from the margins and gaps of the colonial archive. Admiring stories of him and his feats can be found in their thousands in Australian newspapers.

Bob Petersen has written a tremendously rigorous and detailed, if somewhat tedious, biography of Jackson focused on his sporting career. The classicism, the iconography, the immensity of Jackson’s memorial all face towards a future in which Jackson is already in the pantheon of Australian greats.

Perhaps it’s not so much Jackson who needs to be recovered but the Australian public sphere in which he was adored. We need to understand how a man born in the wake of the abolition of slavery in the Danish Caribbean could, by his death in the same year the White Australia policy was adopted, be regarded as the prototypical man.

A heavyweight career

Outwardly, the story of Peter Jackson, boxing champion, is relatively straightforward. On his own account, Jackson “drifted” into boxing in Sydney in the early 1880s. A famous origin story is that he was discovered brawling at Wynard Square with underlings of the gangster “Dixon the Doghanger”. Watching on as Jackson dispatched “Long Alf” and six others was Larry Foley, a middleweight who had recently set up a boxing academy.

Foley would become legendary for his role in developing Jackson. This reputation was enhanced as he went onto train a number of other greats, including the Canadian world champion Tommy Burns.

In fact, Jackson already had an active interest in boxing and had been mentored by the veteran African American boxer Harry Sellars, who moved to Sydney around the same time as him. Jackson is often figured as a lone Black man forging his own path in white colonial Australia, but, as Petersen’s biography and further research by Karina Smith, Gary Osmond and Jan Richardson make clear, Jackson joined a loose community of African diasporic Australians, including several Caribbean migrants.

Most notably Jackson was befriended and mentored by Barbadian-born Jack Dowridge, a one-time boxer and successful businessman in Brisbane. Dowridge stayed in touch with Jackson through his years abroad. He helped him materially in his dying days and saw that he was buried in his own family’s plot in Toowong cemetery.

Jackson would later mentor and help to train another boxer from St Croix, Peter Felix, who arrived 15 years after him. Also active in these circles was Edward “Professor Starlight” Rollins from British Guiana. A generation later, Les Moody, a descendent of a convict from Barbados and the great uncle of the Aboriginal writer Tony Birch, won the Australian bantamweight title. A few years after him, Fred James, who descended from a Bermudan immigrant, won the featherweight title.

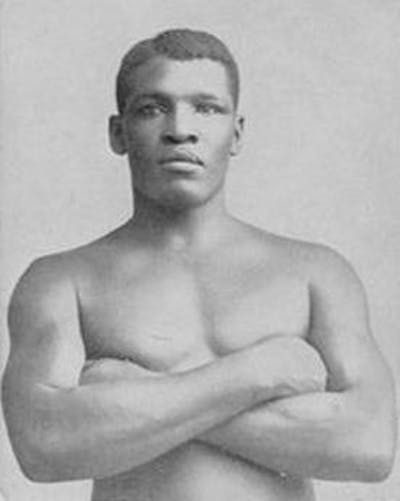

The sport of boxing was in transition in the 1880s. Already wildly popular, it was now professionalising. Trained fighters who analysed strategy and tactics were regarded as “scientific”, as against the brute brawlers who relied on strength. Jackson was resolutely the former. He read the latest manuals and always fought with gloves under the Queensbury Rules.

Jackson’s early career is only fitfully recorded, as he competed against a range of more and less competent fighters to become New South Wales champion. In 1886, he easily beat the Victorian champion Tom Lees to attain the Australian heavyweight belt.

The reporter for the Sydney Bulletin noted that, although the audience was predominantly white, the large numbers of Black people – referred to in derogatory terms – gave the hall a “piebald appearance”. Again, indications of a broader Black diasporic context for Jackson’s feats in Australia.

The Australian title gave Jackson the profile and springboard for an international career and he departed for San Francisco in 1888. The city’s openness to the sport made it a magnet to boxing’s elite, giving it the moniker the “cradle of the fistic stars”. Over the next four years, Jackson went undefeated as he took on the best fighters on both sides of the Atlantic.

Well, those who would fight him. Notoriously, the white US heavyweight “champion” John L. Sullivan refused to fight Jackson on purely racist grounds – what was referred to euphemistically as “drawing the colour bar”. And Sullivan readily admitted it.

In 1891, Jackson was able to secure a fight with another aspirant to the world title, James J. Corbett. Fighting through an injured ankle, Jackson drew Corbett over four hours and 61 rounds in one of the great bouts of world boxing. Corbett used the profile the fight afforded him to challenge Sullivan, whom he beat to become US heavyweight championship.

Corbett then dodged Jackson’s subsequent attempts to get a fight, denying him the chance to be US champion and, thus, official world champion.

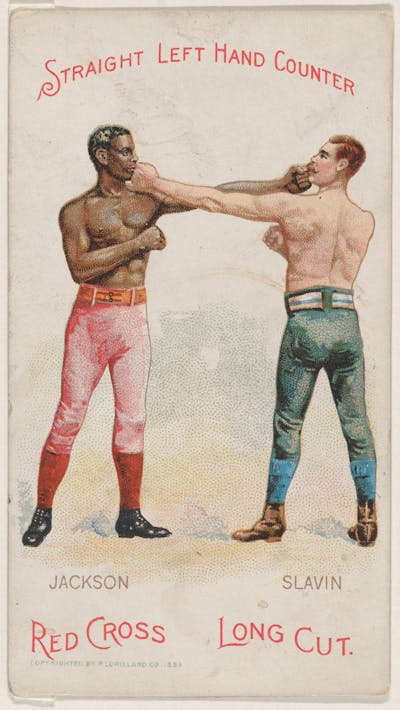

Jackson did secure a fight with another flagrant racist, the Australian Frank “Paddy” Slavin, who claimed to be Australian champion despite not having fought Jackson since he had won the belt in 1886. They had crossed paths and sparred when they were both coming up and were well known to each other when they contested the Commonwealth Heavyweight title at National Sporting Club in London in May 1892.

In lieu of a fight against the US champion, this was the biggest title for which Jackson was able to compete. It was an occasion dripping with narrative possibility, especially for an Australian public learning of its globe-striding stars from afar.

“The rhetorical structure of boxing requires that the men competing inside the ring be ideologically positioned as opposites,” writes cultural historian Jordana Moore Saggese. In an environment of white supremacism, we might expect the fight to be framed according to the usual oppositions of colonial ideology: white versus black, good versus evil, civilization versus savagery.

Jackson’s deportment over his public career and careful cultivation of a gentlemanly reputation short-circuited such facile oppositions. Even so, Slavin was positioned by the Australian public uncomplicatedly as one of “us” (“our picked pet pugilist” in the words of a popular song about the bout), while Jackson’s status was more ambiguous. Sydney’s The Spectator commented wryly that “men, who while Peter had no compeer within sight, were slavish in their adulation; as soon as Slavin seemed to stand nearly on a level […] deserted the tried and true Peter, because of his color forsooth.”

Slavin made it known that he too held racist views about Jackson, despite an ostensible friendship with him.

The bout itself was not a classic. Ever the scientific fighter, Jackson saw off Slavin’s early onslaught with counterpunches, then increasingly heavy direct blows. In the tenth round, he nursed a well-beaten Slavin to the ground, appealing to the referee to end the fight.

By mid-1892, many regarded Jackson as world heavyweight champion. He was thought better than Corbett, whom he had fought to a draw when injured, and had seen off all other challengers. For colonial Australia, this was, to date, far and away the greatest ever global success of any of its sportspeople.

According to the protocols of Australian history, which routinely serves up Donald Bradman and Phar Lap as case studies for high-school students, Jackson ought to be a household name. He was a homegrown talent, he fought in Australian (and St Croix) colours throughout his career, and it was to Australia that he returned when terminally ill in the latter years of his life.

Worimi historian John Maynard commented to us in an interview for our podcast that there was a “whitewashing” of Jackson in the Australian public sphere in his time. Jackson was often said to have the “heart of a white man”. This was a common refrain for successful Black men of African descent. Karina Smith comments that figures like Jackson, Peter Felix and Jack Dowridge were regarded as “honorary whites” within the racial logic of the time.

Indeed, Slavin tried to rescue his reputation in just these terms. Standing before a portrait of Jackson in the National Sporting Club, Slavin is reported to have said: “I lift my hat to the whitest man to have fought in the ring.”

The operative word for Jackson’s supposed whiteness was gentleman. Jackson’s adherence to the codes of dress, deportment and character – ostentatious humility, especially – associated with the gentleman gave the white public permission to identify with him. The choice of white marble to depict the suited Jackson for his memorial seems no coincidence. Black skin, white marble.

Black dandyism

The irony for Jackson is that being cast this way has not been enough for him to hold his place in the Australian public’s imagination. No doubt there are multiple causes for this, not least the diminishment of broad enthusiasm for boxing. Another may be that he ultimately spent just over a quarter of his life in Australia (though the same is true of Clive James). The aura and prestige that accrued to the “gentleman” has also faded. Perhaps it would be better now if Jackson had been known for skulling beers.

I’m not suggesting that successfully appealing to white Australia’s collective imagination and sense of self ought to be a barometer for Jackson’s importance. It is just that national narratives are so often the frameworks for keeping alive the stories of figures like Jackson.

If Jackson is to be recovered (again), should we accept the nationalist logic that dictates whose stories get told? If not, for whom is he recovered?

And for what purposes? A more plural, perhaps even decolonised national Australian identity? Or is this a story of and for the African diaspora, the Afro-Caribbean one especially? Or do Jackson’s peripatetic feats mean he is really one for the annals of global sporting history, and we ought to define sporting success in its own, transnational category?

Like any major historical figure, aspects of Jackson’s story can be cited to support any number of historical narratives. In Jackson’s case, though, there is a particular, perhaps even singular permeability that allows the facts of his life to be shaped in conformity with multiple, often competing narratives.

For one, Jackson was adept at adjusting his accent and linguistic style to his context. His biographer Bob Petersen records that he had an American accent upon arrival in Sydney, a mark of having worked on an US ship. He had a “colonial” accent – which is to say, Australian – on arrival in San Francisco after his decade in Australia, and a “purely English” accent after three years in Britain, and so on. There are also reports of him reverting to a Cruzan vernacular (i.e. from St Croix) when speaking to fellow Black people.

To recreate Jackson’s voice for our podcast, Sienna Brown worked with Sierra Leonean, British actor Alpha Kargbo to blend a Victorian gentleman’s cadence with a Cruzan lilt and Australian twang:

Author provided (no reuse)751 KB (download)Playing on the metaphor of the scientific boxer, Sienna sees this quality as Jackson’s capacity to adopt masks as he “ducked and weaved” through the distinct yet always fraught racial politics found in different corners of the imperial world.

Careful attention to the way Jackson is represented reveals that he was not a passive object of the white gaze.

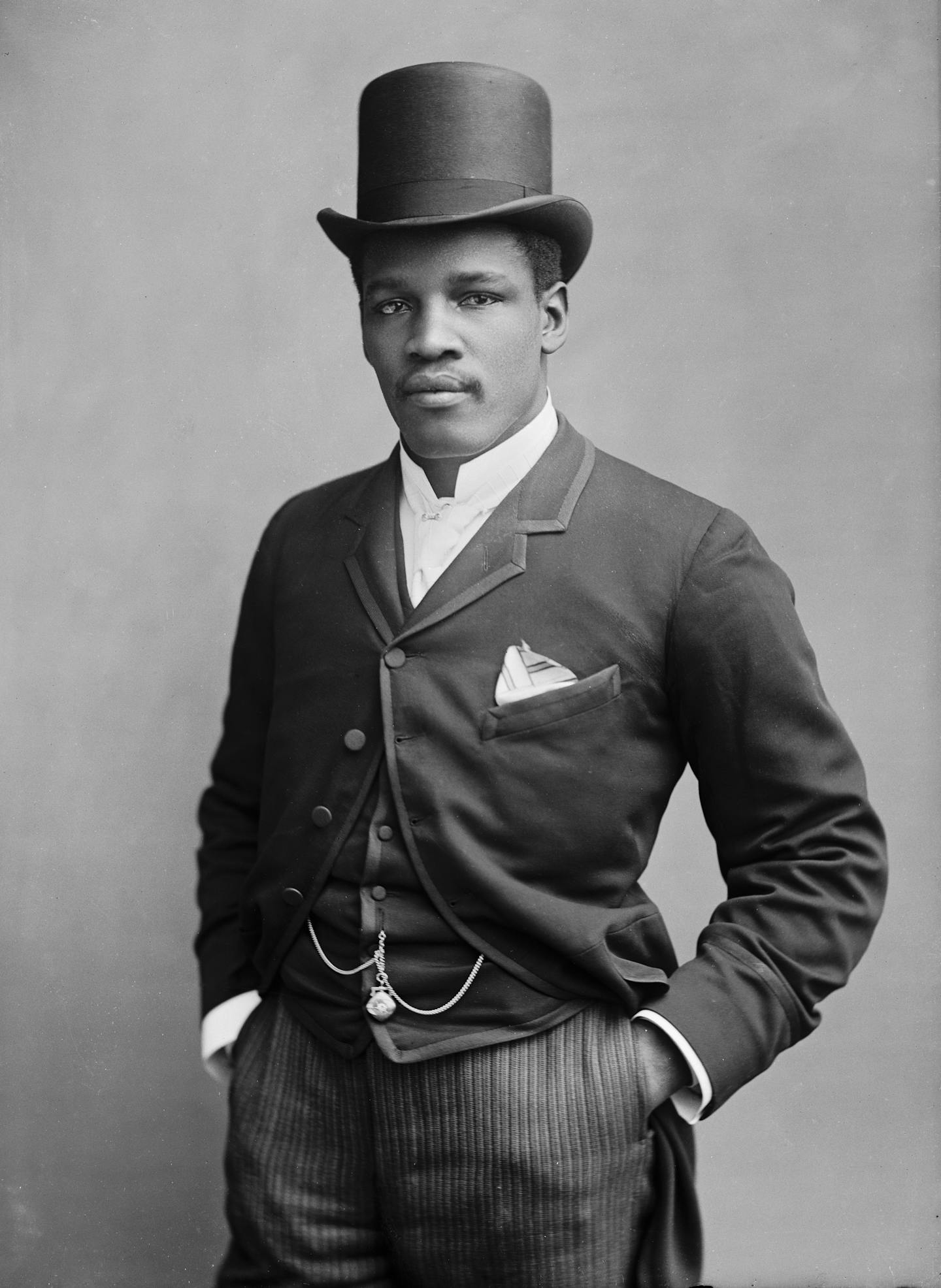

In her brilliant study Heavyweight: Black Boxers and the Fight for Representation, Saggese highlights how Jackson actively shaped his public image. She pays particular attention to a series of photographs that Jackson had made at a studio on Oxford Street in London in 1889. He was 29 and in the middle a string of storied international bouts.

The top hat, the suit jacket spread to reveal vest and delicate pocket watch, the calm confident gaze into the lens, and, importantly for a boxer, the casually pocketed hands all alert Saggese to a man who is projecting himself as “a classic London gentleman, a dandy even”, as he “fashions an image of himself outside his identity as a boxer”.

If this portrait speaks to the dress and iconography of the Victorian gentleman, it also sits within the tradition of Black dandyism, first brought prominently to attention by cultural historian Monica Miller. The Black dandy, for Miller, is “a creature of invention who continually and characteristically break[s] down limiting identity markers and propose[s] new, more fluid categories within which to constitute themselves.”

A significant precursor for Jackson is American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whose impeccable dress in “white men’s clothing” and use of lithography and photography were key to his success as an abolitionist and civil reformer.

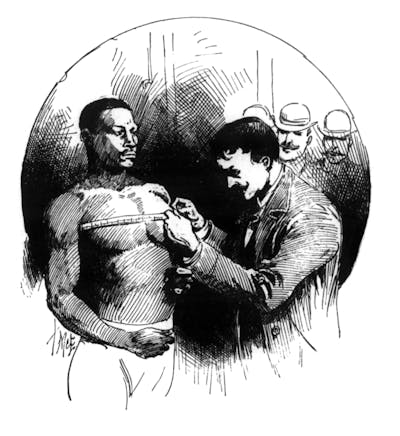

Jackson’s success in self-branding led him to feature in public debates about contemporary embodiments of the classical archetype of the “perfect man”. Saggese documents how Jackson submitted himself to be measured for “the Benefit of Science” as part of these exchanges. Jackson turned the use of measurement to objectify and classify colonial subjects on itself. He was “not marked as Other”, writes Saggese, but forwarded as a model of “the most perfect representation of health, strength and development”.

When it was put to him by a white journalist that he was the equal of classical antecedents, Jackson replied:

This inclination nowadays is to compare alleged perfect men with the old Grecian athletes and Roman gladiators […] I consider the Highland Scotchmen to come as near to my idea of perfection as any. I have also seen splendidly put-up Sikhs and Hindoos for an athletic turn, while if photographs and pictures are to count for anything the Zulus have some splendid specimens of manhood among them.“

The comment puts paid to any notion that Jackson aspired to be an honorary white man. He pointedly nominates counterexamples among colonised peoples, subtly subverting the assumptions underpinning the public debate.

This was a self-fashioning man

Saggese’s analysis and visual contextualisation of Jackson reveal a man especially gifted in self-fashioning. And self-fashioning, as literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt argued of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, is not about conformity to existing culture. It is about how cultivating subjectivity shifts culture.

And it is in this respect that Peter Jackson’s achievements transcend his boxing triumphs. The Shakespeare epigraph on his grave – "this was a man” – speaks to how he expanded the ground of the human in the British imperial world, not to how he conformed to existing norms.

Not all of Jackson’s efforts at self-fashioning were unbridled successes. After he beat Paddy Slavin, and as he tried to secure the fight that would give him unambiguous status as world champion, Jackson did what many boxers of his day did: he leveraged his fame to make money in the theatre.

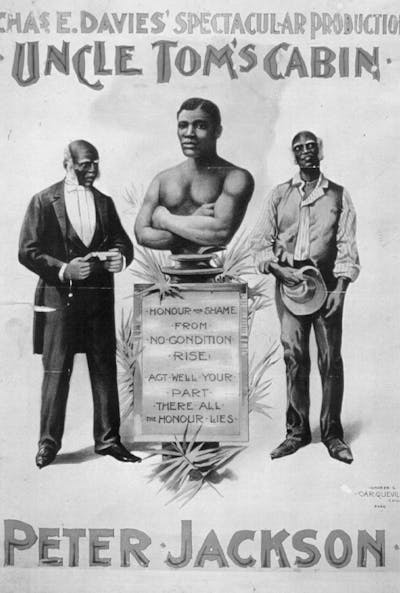

White boxers often had productions written specifically for them in alignment with their public profile. Jackson was fond of quoting Shakespeare in his public appearances – another string to his gentlemanly bow – and wanted to play Othello. But he was offered the role of Uncle Tom in a touring production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1894.

In an interview for our podcast, Saggese commented that playing a role that had come to typify white liberal fantasies about enslaved people as noble yet submissive shows Jackson’s “complete misunderstanding of racial politics in the United States”. As if to emphasise the discrepancy with his established public image, the play’s poster juxtaposes the image of Jackson playing Uncle Tom in all his naïve piety with a pseudo-classical bust of Jackson the boxer.

The episode indicates the limits of Jackson’s self-branding and use of the mass media. He wasn’t always able to duck and weave his way through the perils of being a racialised subject, particularly in the context of postbellum United States.

Ducking and weaving

As Sienna and I explored Jackson’s life, his successes, his failures, and his premature demise from tuberculosis at the age of 40, we realised that we didn’t have a story that fit into received narratives, and certainly not one that readily answers to the political imperatives of our time. What perhaps has gone missing in the many revivals of Jackson is an understanding of him as a Caribbean man, who is part of a longer history of the Caribbean presence in Australia.

As recent historical explorations have revealed, not least Sienna’s previous efforts to recover the lives of Black West Indian convicts, Jackson was part of a small but constant Caribbean diaspora, whose presence in this country is as long as that of the white British diaspora.

Though never sizeable enough to attain the institutional prominence of larger immigrant groups, there are discernible patterns that give the West Indian diaspora cultural continuity in Australia. One is a shared set of cultural habits, but also hostilities and rivalries, forged within the British empire and its long cultural legacies.

This is not, as is often touted, a matter of cricket only. To cite just one point of connection: John Maynard discussed with us how Aboriginal dock workers came into contact with anticolonial ideas partly through contact with West Indians, especially those connected to the Garveyist movement, founded by the Jamaican-born activist Marcus Garvey.

Jackson may have been born in a Danish-Caribbean colony, but its dominant language was English and he attended an Anglican school. His capacity to project himself as a “gentleman” and his ease with the markers of transnational anglo identity were culturally shared traits, not something Jackson deployed just for PR.

A second less tangible quality Sienna identified in our explorations of Jackson, is that very ability to “duck and weave” when navigating the social complexities of new situations. She attributes this quality to Jackson being born into a Creole society, in which the distribution of power through gradations of colour and class engendered cultural practices of “code-switching” and “code-mixing”.

This is not Jackson as chameleon, and certainly not as assimilating “honorary white” but as a Creole man, whose cultural capabilities allowed him to navigate through complex social fields in pursuit of his ambitions.

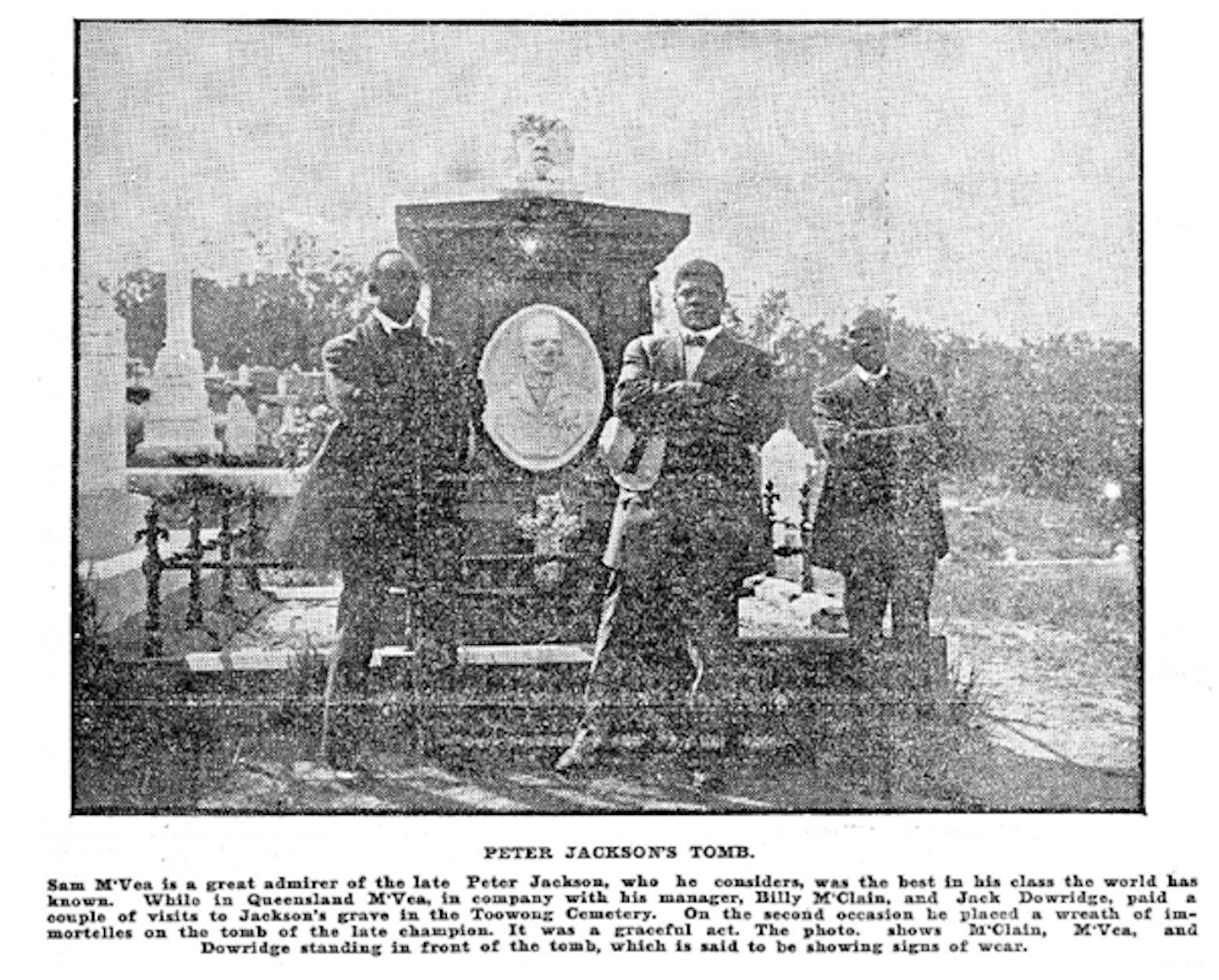

When the African-American heavyweight boxer Sam McVea visited Australia in 1911, he was taken twice to Jackson’s grave in Toowong cemetery by Jackson’s friend, the Barbadian-born businessman Jack Dowridge. Dowridge had also taken Jack Johnson, the first official Black heavyweight world champion, to the grave three years earlier.

On the second trip, McVea laid a wreath of immortelles in the same place below Jackson’s bust that Sienna and I found the pair of boxing gloves. In a photo snapped for the Evening Standard, Dowridge, McVea and McVea’s manager stand with arms crossed either side of the bust.

Like Jackson, each wears a suit, even though it was a hot summer’s day the week before Christmas.

There’s a seriousness in their demeanour, perhaps even a sense of defiant pride, of guarding a tradition, just as the lion perched on the grave guards over Peter. The burnt grass, the gum trees lining the horizon: this is Australia.

This essay is based on podcasts produced for History Lab by UTS Impact Studios.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ben Etherington, Western Sydney University

Read more:

- Today’s AI hype has echoes of a devastating technology boom and bust 100 years ago

- Caught in Nepal’s protests, I witnessed how sport can bring people hope during times of crisis

- Commuters have bemoaned Philly’s public transit for decades − in 1967, a librarian got the city to listen

Ben Etherington receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Federick News-Post

The Federick News-Post WCPO 9

WCPO 9 The Motley Fool

The Motley Fool MLB

MLB Bitcoinist

Bitcoinist Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News The Fashion Spot

The Fashion Spot