In the course of construction work in 2013, the remains of 36 individuals of African descent were uncovered in the heart of downtown Charleston, South Carolina. They had lain hidden for some 200 years in an unmarked 18th-century burial ground.

For more than two centuries, such burial grounds, especially those in the former American slave states, have often been erased or obscured – paved over by parking lots, built upon by highways or private development, or simply left unknown and untended. In recent years, descendant communities in places such as Bethesda, Maryland, Richmond, Virginia, St. Petersburg, Florida, and Sugarland, Texas, have called for greater recognition and respect for these long-neglected sites.

As a public archaeologist and educator who has spent over a decade working in Charleston, South Carolina, I co-direct the Anson Street African Burial Ground project – the community-led effort to honor and respectfully lay to rest the 36 African ancestors whose remains were uncovered in 2013.

This Charleston project reflects a growing recognition of African American burial grounds as important historical memory sites and unique sources of genealogical information. Yet there is still limited public understanding about how engaging with these places of sacred rest can promote collective healing, reconciliation and cross-cultural understanding.

Cemeteries obscured by history

Since the British colonial period, racist laws and customs across America prevented enslaved and free people of African descent from using white burial grounds to bury their dead. On plantations, enslavers controlled where and how the enslaved were buried and whether burials could be marked or visited. In cities from Charleston to New York, segregated burial grounds, many now forgotten, were established by local authorities for indigent Black and white people.

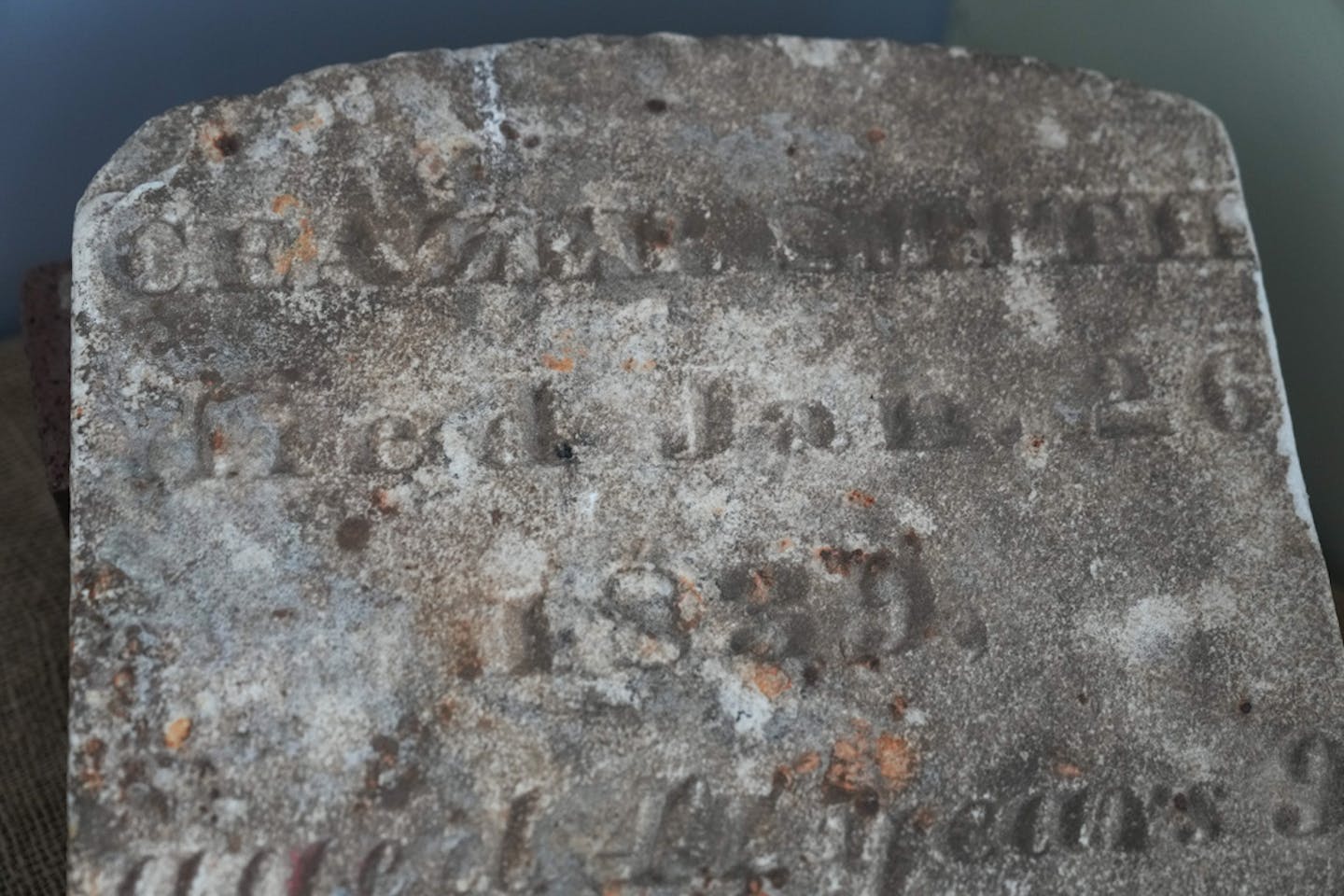

Pushed to the margins, people of African descent maintained burial traditions and used impermanent or specific grave markers such as shells, bottles, clocks or ceramics – items that were culturally meaningful but often invisible or unimportant to white observers. As a result, many of these sites were neither recorded in historical documents nor officially recognized as burial grounds.

From the 1770s, African American churches, benevolent societies and funeral homes sought to establish cemeteries where Black communities could honor the dead with dignity. What began regionally – especially in Charleston and Philadelphia – quickly spread nationally during the 19th century across the American South and North.

In the decades after Reconstruction, and especially during the Jim Crow era, nearly 6 million African Americans moved north and west to escape racial violence and seek better opportunities – an event known as the Great Migration. This movement often severed ties between families and ancestral burial grounds in the South. As churches and burial societies lost members, many cemeteries fell into disrepair and were officially labeled “abandoned” by local authorities or developers.

In both rural and urban areas, Black burial grounds were often located on less valuable lands, sites that today are increasingly threatened by gentrification, development and the effects of climate change.

The Gullah Geechee, who descend from enslaved Africans from West Africa and still preserve unique cultural traditions in the southeastern U.S., argue these burial sites were never abandoned and that ancestors are still present. This perspective views the dead as actively connected to the living. For them, lacking formally designated cemetery space doesn’t make the sites any less sacred.

A tradition of sacred spaces

For many African Americans, especially in the South, death during slavery was seen as not merely an ending but a spiritual return — a “homegoing.”

Rooted in West African spiritual worldviews and carried through other traditions in America, the act of burial was often viewed as a release from bondage, a return to the ancestors and a step toward wholeness.

The Gullah Geechee traditions of coastal South Carolina emphasize ancestral presence, spiritual continuity and the sanctity of the land. In that worldview, with a porous boundary between the living and the dead, proper burial and remembrance are not only cultural imperatives but necessary for community well-being.

It was not until the early 1990s that recognition of rights over ancestral remains and sacred burial grounds began to find a wider audience.

Inspired by the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act that recognized Indigenous rights over ancestral remains, African American communities increasingly asserted their own rights to ethical research, respectful handling and meaningful memorialization, especially during the 1991 New York African Burial Ground project, which reshaped public memory and archaeological ethics.

Discovered during construction in lower Manhattan, the 18th-century burial ground contained the remains of more than 400 enslaved and free Africans. Community advocacy led to the site’s protection, descendant-led research, ceremonial reburial and the establishment of a national memorial in 2006.

Since this time, across the U.S. and the Atlantic world, descendant-led ceremonies from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Key West, Florida, have restored dignity to ancestral remains.

Meanwhile, efforts to preserve African American burial grounds, including by national scholar organizations and federal lawmakers, continue amid political debates over how history should be remembered and taught.

What made the Anson Street project unique

In Charleston, the Anson Street African Burial Ground project stands out for the way Gullah Geechee traditions and descendant collaboration shaped every stage of the process — from scientific study to reinterment.

Launched as a community-led initiative in 2017, the team began by listening. Through regular gatherings, they invited questions about the ancestors’ lives and identities, and about their hopes for the reburial, centering Black community voices at every stage. The team combined scientific investigations of ancestry and health while also creating space for spiritual guidance, ceremony and descendant leadership. In doing so, the project became more than a study of the past; it became a communal act of repair and remembrance, reconnecting Charleston’s present communities with the ancestors whose stories had long been buried.

Over the next two years, the team wove this commitment into every aspect of its work: youth art programs, a college course on memorial design, public exhibitions, and school partnerships. One of the most moving moments came from conversations with schoolchildren, who decided that the ancestors should be given names before they were reburied.

That naming ceremony took place in April 2019. The names were conferred by Natalie Washington-Weik, a Yorùbá-Orisa Ọ̀ṣun priestess, a spiritual leader in a West African tradition and an African historian. She described the ritual as an “important step forward in reclaiming the humanity of the deceased people who were most likely forced to travel across the Atlantic Ocean under the terror of other humans – who saw them merely as animals.”

The ancestors were finally reinterred in a powerful public ceremony that reflected their ancestries and West-Central African spiritual traditions.

When pain is acknowledged, healing can occur

The 2019 naming and reinterment ceremonies were not simply commemorations; they were rituals of remembrance and healing.

Construction for a permanent memorial at the Anson Street site, designed by artist Stephen L. Hayes Jr., has now begun. At its center is a basin fabricated with sacred soil collected from 36 African-descended burial grounds across the Charleston region. From the basin, 36 bronze hands will rise – cast from living community members whose profiles reflect those of the ancestors. Raised in gestures of prayer, resistance and reverence, these hands link past to present.

Throughout the memorialization process, community members reflected on what it meant to participate in such a project. Many spoke of feeling pride, reverence, joy, sadness and peace. “This conversation makes me feel complete,” one participant said.

As Charleston demonstrates, these projects are not only about preserving the past – they are acts of recognition, respect and reconciliation, helping communities nationwide confront and honor the histories long denied to African-descended peoples.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Joanna Gilmore, College of Charleston

Read more:

- Black deaths matter: The centuries-old struggle to memorialize slaves and victims of racism

- More than 100 years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, lessons from my grandfather

- Black communities are using mapping to document and restore a sense of place

Joanna Gilmore has received funding from the City of Charleston, the National Geographic Society, and the College of Charleston. She previously worked for the Gullah Society, Inc. a not-for-profit organization.

The Conversation

The Conversation

WTOP

WTOP The Daily Sentinel

The Daily Sentinel Salisbury Post

Salisbury Post The Atlanta Journal Constitution

The Atlanta Journal Constitution Brooklyn Paper

Brooklyn Paper St. Louis Post-Dispatch

St. Louis Post-Dispatch KLCC

KLCC KSNB Local4 Central Nebraska

KSNB Local4 Central Nebraska The Post and Courier

The Post and Courier Bored Panda

Bored Panda Crooks and Liars

Crooks and Liars