One of the earliest figures known to have faked an illness for personal advantage was Odysseus.

Odysseus was the hero of Homer’s Odyssey, which was probably written around the 8th century BC, but based on much older legends.

According to one version of the story, Odysseus pretended to be mentally ill to avoid taking part in the war of the Greeks against Troy.

To show he was not sane enough to go to war, Odysseus ploughed sand instead of soil, and did other wild deeds. However, his lie was exposed.

Palamedes, one of the leading figures on the Greek side of the war, threw Odysseus’ baby son, Telemachus, in front of Odysseus’ plough. Odysseus stopped to protect his son, showing he was not mentally ill.

Pretending to be ill to gain some personal benefit – such as trying to avoid work or war – is something ancient and modern people have in common.

As we’ll see, “taking a sickie” has a long history.

The Roman slave with a ‘sore knee’

The Greek physician Galen of Pergamum (129–216 AD) was familiar with the phenomenon of people pretending to be sick.

In one of his many books, he provides the most detailed ancient account we have of a doctor with a patient who fakes an illness.

Galen describes how a Roman slave boy tries to get out of doing his work by claiming he has severe pain in his knee.

As part of his deception, the slave smears poisonous ointment over his knee to make it look like it is swollen and bruised:

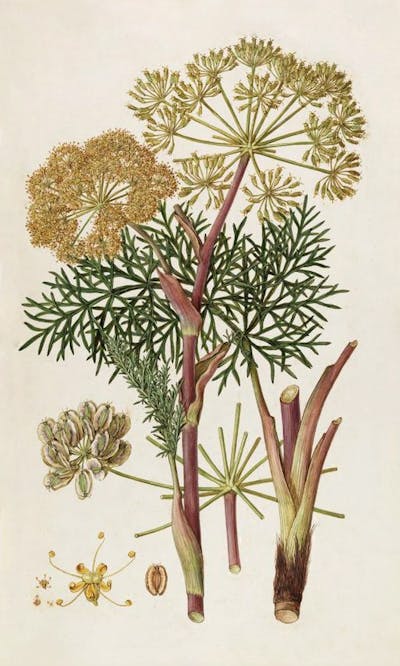

The slave boy had a large swelling at the knee which would frighten people who know nothing about medicine, but someone with medical expertise knows clearly that it was produced by the drug called ‘thapsia’.

This was Thapsia garganica, a poisonous plant that causes inflammation and swelling.

Galen could also tell this was a fake injury from the slave’s contradictory accounts of his pain. The slave said, at one point:

‘I feel tension in my whole joint’ and at another: ‘I feel a throbbing inside it’, and yet another: ‘it feels like there is an arrow stuck in it’ or: ‘it feels like it was pricked with needles’ or: ‘it feels heavy like a stone’, then ‘I feel pain in my whole leg in this way’ and then ‘the bone feels weak’.

Galen also gives the slave a fake cure to see how he responds:

I said to him: ‘I am going to rub a drug on your knee, and the pain you have will stop immediately’. I then rubbed a drug on it that does not at all relieve pain but usually only cools the heat generated by the thapsia. That slave confirmed after just a short while that his pain had gone completely. Had this pain really been caused by a hot swelling brought about by an internal cause, this cooling medicine would have intensified the pain and certainly not relieved it.

After the slave boy’s lie was exposed, he had to go back to work.

How to spot a faker

Galen also advised doctors on how to find out whether a patient was faking their illness. This included instructing doctors to tell their patients what they would have to give up to get better:

Some people are fond of drinking wine, some are fond of food, […] some are fond of bathing at the baths and some are fond of sex.

Clearly, Galen thought people wouldn’t want to pretend to be sick if they had to give up doing their favourite things or eating their favourite foods and drinks while receiving treatment.

Is faking an illness ever justified?

People in ancient times are shown faking all kinds of illnesses for personal advantage, mainly to get out of work, military service, or to conceal an affair.

However, in extreme cases lying may have been justified.

In Xenophon of Ephesus’ novel The Ephesian Tale (2nd–3rd century AD), the heroine Anthia avoids being sold into prostitution by faking an epileptic fit.

She then lies by saying she has always suffered from epilepsy, and is set free.

Modern sickies

In modern times, “taking a sickie” has become a well known phenomenon.

We’ve all seen the stories about people calling in sick and then their bosses seeing them on TV or social media boozing at the cricket or footy.

If the phenomenon of “taking a sickie” tells us anything, it’s that illness generates sympathy, and sympathy causes us to allow sick people time away from their duties – but this sympathy can be exploited for personal gain.

Galen knew that well, some 2,000 years ago.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Konstantine Panegyres, The University of Western Australia

Read more:

- From potion to prescription: how witches’ herbs became medical marvels

- Is it dangerous to catch a cold… or was Jane Austen just being dramatic?

- GPs will soon get extra incentives to bulk bill. So will your doctor be free?

Konstantine Panegyres does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News Real Simple Home

Real Simple Home Fast Company Lifestyle

Fast Company Lifestyle News on 6

News on 6 cleveland.com

cleveland.com Raw Story

Raw Story New York Post Video

New York Post Video AlterNet

AlterNet OK Magazine

OK Magazine The radio station 99.5 The Apple

The radio station 99.5 The Apple