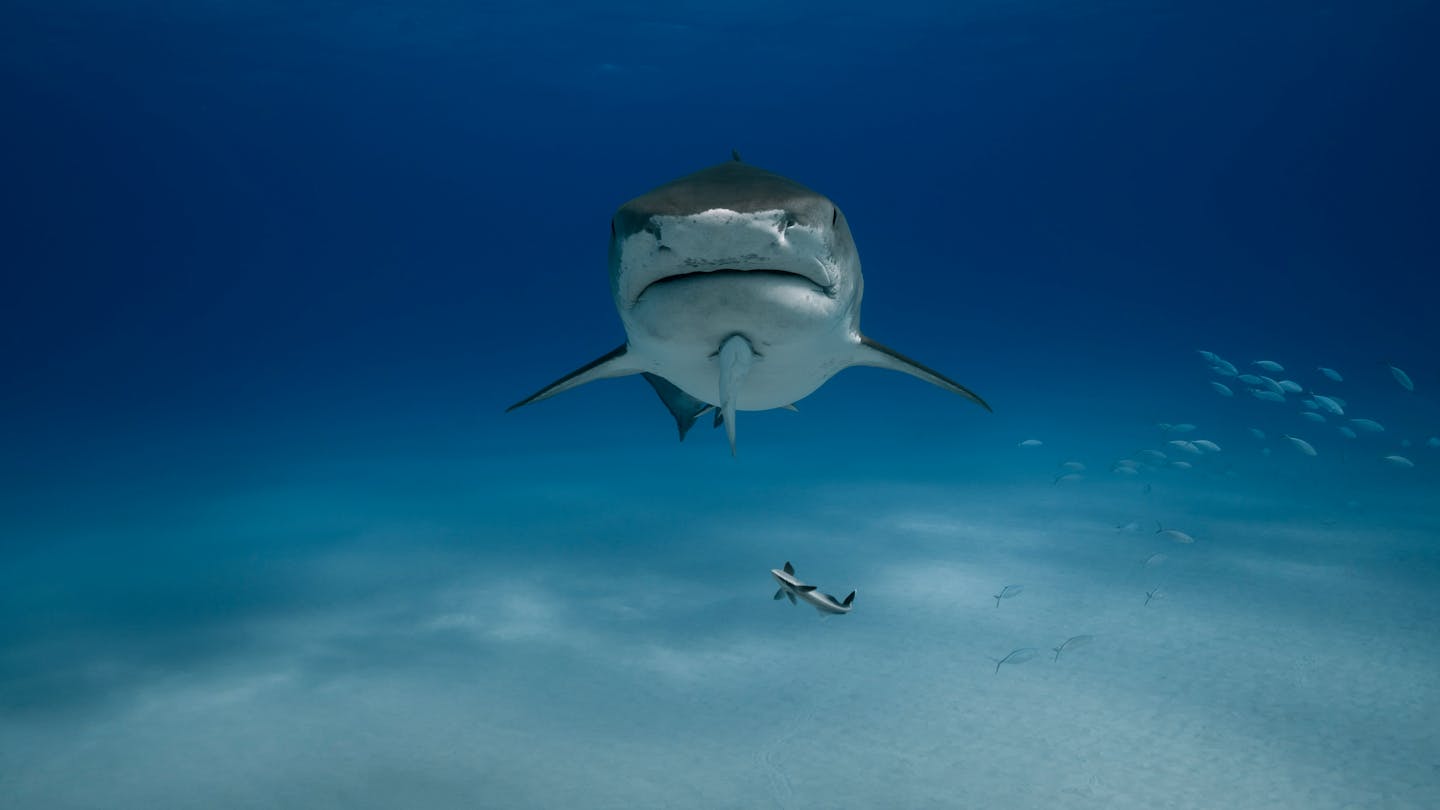

When you picture a shark, you probably think of a large, powerful predator cruising the open ocean.

Species such as the great white shark, tiger shark and bull shark dominate popular media, with stories of rare and isolated cases of attacks on humans (such as the tragic death of surfer Mercury Psillakis last Saturday on Sydney’s northern beaches) instilling a widespread fear of sharks in the public, and influencing government policy. For example, the expanding use of shark nets and other “control equipment” across Australia.

While these three species are certainly charismatic predators, they represent less than 0.6% of living sharks. The more than 500 species of living sharks exhibit an astounding diversity of shapes and sizes, from giant 20-metre-long whale sharks to phone-sized bioluminescent lanternsharks, flattened angel sharks, hammerheads, sawsharks, goblin sharks and wobbegongs.

But how did sharks become so diverse? A new study I led investigated the evolution of body shape in sharks from their ancient ancestors more than 400 million years ago, all the way to the present day.

A time before the dinosaurs

The huge variation in body shapes we see today did not appear overnight – the shark lineage traces back to a time before the dinosaurs.

Scientists often use fossils to recreate shifts in body shape and size across the evolutionary tree of different animal groups. Unfortunately, we can’t do the same thing with sharks.

That’s because shark skeletons are made of cartilage instead of bone. So unlike mammals, birds or reptiles, we don’t have many complete fossils of ancient sharks. Instead, we have loads and loads of isolated fossil teeth.

This means that, until now, scientists have known very little about how, when and why the huge diversity of shark body types we see today evolved.

Instead of using fossils, we collected information about body shape from scientific illustrations of more than 400 living shark species, and used a statistical method called ancestral state reconstruction to estimate the body shape of ancient sharks.

We also collected information about the habitats that different shark species prefer – and how environmental conditions have shifted since the emergence of the very first sharks.

Ancient sharks were bottom-dwellers

Our analyses suggest ancient sharks were probably benthic – meaning they lived on or close to the sea floor. Pelagic sharks that roamed the open ocean and resembled today’s large iconic predators such as great white, tiger or bull sharks, did not arise until the Jurassic period 145–201 million years ago, at the very earliest.

This means that, for the first half of their existence, sharks were restricted to habitats close to the sea floor.

Why? Interestingly, we found that three of the four times sharks have colonised the open ocean, there was a shift in body shape (including the evolution of a deeper body and more symmetrical tail) that occurred just before the shift in habitat.

The timing of these shifts also indicates historical climate change (including rising sea levels and tectonic shifts) may have played a crucial role in creating more pelagic habitats these sharks could have colonised.

This means that as the climate changed, so too did the habitats that ancient sharks inhabited, enabling the evolution of new body shapes. And it so happened that these deeper bodies with more symmetrical tails were better suited for open-water living.

Better understanding ancient ecosystems

By looking back in time at what ancient sharks looked like and how they might have lived, we can better understand how ancient ecosystems functioned, and predict how they may respond to future human-made climate change.

More broadly, these results showcase that not all sharks are the same. Most sharks – both ancient and living – are small and benthic, not large, dangerous apex predators.

So the next time you picture a shark, think not only of great whites and tigers, but also of the ancient bottom-dwellers that shaped the seas long before the first dinosaurs.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Joel Gayford, James Cook University

Read more:

- New research indicates caribou populations could decline 80 per cent by 2100

- One queen ant, two species: the discovery that reshapes what ‘family’ means in nature

- 5 forecasts early climate models got right – the evidence is all around you

Joel Gayford receives funding from the Northcote Trust.

The Conversation

The Conversation

FOX News

FOX News Vogue Living

Vogue Living New York Post

New York Post The Travel

The Travel ABC 7 Chicago Politics

ABC 7 Chicago Politics Raw Story

Raw Story America News

America News New York Post Video

New York Post Video Atlanta Black Star Entertainment

Atlanta Black Star Entertainment