When Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, it was the largest climate bill in U.S. history, with major incentives for electric vehicle production and adoption. In its wake, investment in the U.S. electric vehicle industry accelerated. But in 2025, President Donald Trump’s so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act eliminated most of the incentives, and U.S. investment collapsed.

Hitting the brakes on electric vehicles will clearly mean less progress in reducing transportation emissions and less strategic U.S. leadership in a key technology of the future. But in a new study, my colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University and I find that fewer electric vehicles will also mean less investment to clean up the electricity sector.

How we got here

U.S. electric vehicle adoption lags behind the rest of the world – especially China, which has invested heavily and strategically to dominate electric vehicle markets and supply chains and to leapfrog the historical dominance of American, European and Japanese manufacturers of vehicles powered by internal combustion engines.

Electric vehicles are much simpler to engineer, and this opened a window for China to bet big on EVs with investment, incentives and experimentation. As battery prices dropped dramatically, electric cars became real competition for gasoline cars – especially for the massive Chinese market, where buyers don’t have strong prior preferences for gasoline. China now dominates the supply chain for battery materials, such as lithium, nickel, cobalt and manganese, as well as the rare earth minerals used in electric motors.

In 2022, the U.S. took action to change this trend when Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act. The law encouraged EV adoption by lowering costs to manufacturers and consumers. But it also encouraged automakers to find ways to build EVs without Chinese materials by making the largest incentives conditional on avoiding China entirely.

After the law passed, investment soared across hundreds of new battery manufacturing and material processing facilities in the U.S.

But in 2025, Congress passed and Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which eliminated most of the incentives. U.S. investment in EV-related production has collapsed.

Electric vehicles are cleaner

As a scholar of electric vehicle technology, economics, environment and policy, I have conducted numerous peer-reviewed scientific studies characterizing benefits and costs of electric vehicles over their life cycle, from production through use and end of life. When charged with clean electricity, electric vehicles are one of the few technologies in existence that can provide transportation with near-zero emissions.

With today’s electricity grid, EV emissions can vary, depending on the mix of electricity generators used in the region where they are charged, driving conditions such as weather or traffic, the specific vehicles being compared, and even the timing of charging. But EVs are generally better for the climate over their life cycle today than most gasoline vehicles, even if the most efficient gas-electric hybrids are still cleaner in some locations. EVs become cleaner as the electricity grid becomes cleaner, and, importantly, it turns out that EVs can even help make the electricity grid cleaner.

This matters because transportation and electricity together make up the majority of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, and the passenger cars and light trucks that we all drive produce the majority of our transportation emissions.

In its efforts to prevent the government from regulating greenhouse gas emissions, the Trump administration is now claiming that emissions from cars and trucks are “not meaningful” contributors to climate change. But in reality, a technology that cleans up both transportation and electricity at the same time is a big deal.

An opportunity for cleaner electricity

Our research has found that turning away from electric vehicles does more than miss a chance to curb transportation emissions – it also misses an opportunity to make the nation’s electricity supply cleaner.

In our paper, my co-authors Lily Hanig, Corey Harper and Destenie Nock and I looked at potential scenarios for electric vehicle adoption across the U.S. from now until 2050. We considered situations ranging from cases with no government policies supporting electric vehicles to cases with enough electric vehicle adoption to be on track with road maps targeting overall net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

In each of these scenarios, we calculated how the nation’s power grid and electricity generators would respond to electric vehicle charging load.

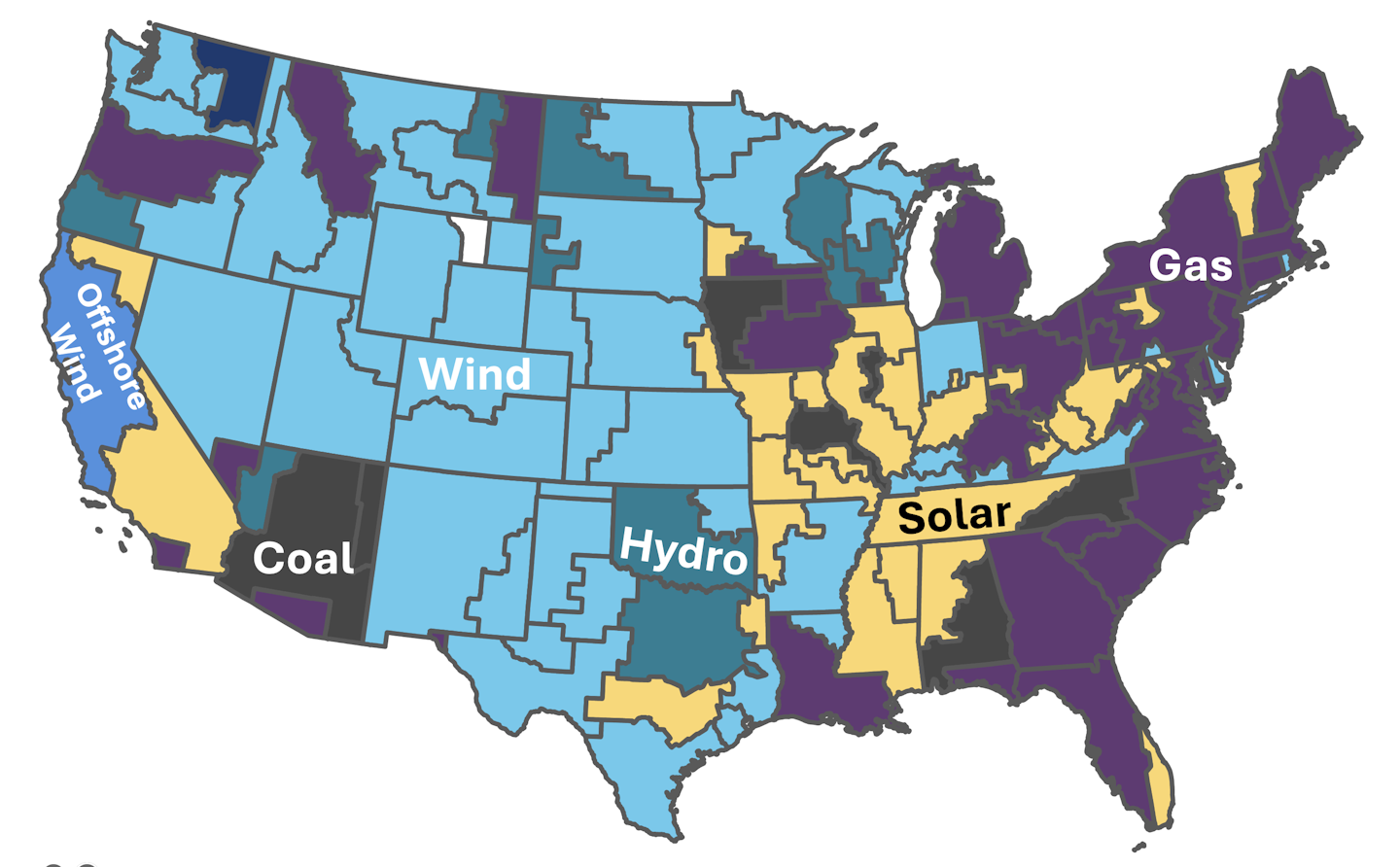

We found that when there are more electric vehicles charging, more power plants would need to be built – and because of cost competitiveness, most of those new power plants would be solar, wind, battery storage and natural gas plants, depending on the region.

Once wind and solar plants are built, they are cheaper to operate than fossil fuel plants, because utilities don’t need to buy more fuel to burn to make more electricity. That cost advantage means wind and solar energy gets used first, so it can displace fossil-fuel generation even when EVs aren’t charging.

A virtuous – or vicious – cycle

Our analysis reveals that what’s good for climate in the transportation sector – eliminating emissions from vehicle tailpipes – is also good for climate in the power sector, supporting more investment in clean power and displacing more fossil fuel-powered generation.

As a result, encouraging electric vehicle adoption is even better for the climate than many people expected because EV charging can actually cause lower-emitting power plants to be built.

Gasoline vehicles can’t last forever. The cheap oil will eventually run out. And EV batteries have gotten so cheap, with ranges now comparable to gas cars, that the global transition is already well underway. Even in the U.S., consumers are adopting more EVs as the technology improves and offers consumers more for less. The U.S. government can’t single-handedly stop this transition – it can only decide how much to lead, lag or resist. Rolling back electric vehicle incentives now means higher emissions, less clean energy investment and weaker U.S. competitiveness in a crucial industry of the future.

Our findings show that slowing electric vehicle adoption doesn’t just affect emissions from transportation. It also misses opportunities to help build a cleaner power sector, potentially locking the U.S. into higher emissions from its top two highest-emitting sectors – power generation and transportation – while the window to avoid the worst effects of climate change is closing.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jeremy J. Michalek, Carnegie Mellon University

Read more:

- China’s electric vehicle influence expands nearly everywhere – except the US and Canada

- EPA removal of vehicle emissions limits won’t stop the shift to electric vehicles, but will make it harder, slower and more expensive

- Why predicting battery performance is like forecasting traffic − and how researchers are making progress

Jeremy J. Michalek currently receives funding from Toyota Research Institute and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory to study electric vehicle battery recycling and reuse and from the Technology Competitiveness and Industrial Policy Center to study global supply of critical battery materials. He has received funding from a diverse group of sources in the past, such as the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, the Department of Transportation, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Bureau of Economic Research, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Electric Power Research Institute, Ford Motor Company, Toyota Motor Corporation, the Center for Applied Environmental Law and Policy, and other organizations. He has consulted for the US Environmental Protection Agency. The views expressed here are his own.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Reuters US Politics

Reuters US Politics Reuters US Domestic

Reuters US Domestic America News

America News AlterNet

AlterNet Raw Story

Raw Story Local News in New York

Local News in New York Associated Press US and World News Video

Associated Press US and World News Video