The Nature of Gothic, at the Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery, explores the history of decorative borders over hundreds of years. It covers the period from the late medieval age to the Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

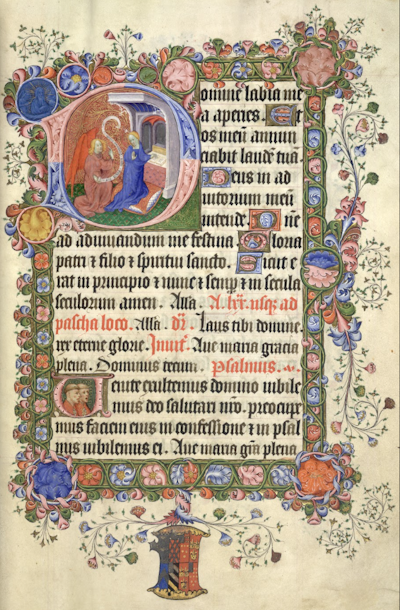

In the late medieval period, manuscripts that were produced in northern Europe often featured decorative borders that framed the text of both religious and secular works. These borders featured motifs from the classical world such as swirling acanthus leaves, Greek meanders and intricate patterns which interlace flowers, leaves and vines.

From the early decades of the 13th century these largely naturalistic forms, used to enhance the visual appeal of the page, began to be used more widely. They were added to the front of books and important sections within them, such as the beginnings of individual psalms or chapters of the Bible.

These naturalistic frames provided platforms tangible enough for figures, animals and grotesques to be placed upon. These characters often present an alternative reality to the verses of the psalms or Aristotle’s Libri Naturales that they decorate.

The meaning and intent of these spaces is yet to be fully understood. The battle of a miniature knight versus a fully armed snail, for example, might be interpreted as the moral fight against evil in the margins of the psalm. But the meaning of a tiny man pushing another in a wheel barrow adjacent to the beginning of Aristotle’s Libri Naturales is less clear.

Read more: Why medieval manuscripts are full of doodles of snail fights

The great enthusiasm for the illustrated grotesques (hybrid creatures which combine human and fantastical animal forms) in these peripheral spaces began in northern France. Texts produced by the monastic schools which emerged with the rise of scholasticism in the late 12th century often carried this type of decoration.

I have been collaborating with the Blackburn museum for over a decade, and have curated this exhibition alongside Anthea Purkis, its curator of art. This exhibition features some early examples of this technique from manuscripts held by the museum as well as examples on loan from the British Library.

In the exhibition

Although the names of very few medieval artists whose work appeared in manuscripts are known, Blackburn Museum and the British Library both hold examples of the intricate and sophisticated work of two known illuminators.

They are Mâitre Françoise, who ran his business in Paris in the third quarter of the 15th century, and Herman Scheere – perhaps the most renowned illuminator in London in the 15th century.

From his workshop on London Bridge, Scheere produced flowing extravagant frames for the pages of his books. His book the Bedford Psalter and Hours, (loaned by the British Library and on display in the exhibition) was commissioned by the younger brother of King Henry V. This aristocratic commission demonstrates the success of Scheere’s business and the appetite for the decorated border.

Some 15th century examples from northern Europe also show the influence of Islamic art on northern European aesthetics. A 15th-century Qur'an manuscript from the John Rylands Library and Research Centre in Manchester is on display in the exhibition. muh .aqqāq script is used for Arabic primary text while the interlinear script in Persian and Eastern Turkish is in minuscule naskh script. This reflects the various communities for whom the book was intended.

The beginnings of the chapters of the Qur'an manuscript, the ṣuwwar, are surrounded by borders filled with flowing abstract forms. They’re reminiscent of, but not imitative of, the natural world. This decorative tradition would have cross pollinated with western European cultures through trade and conflict.

Examples of Persian calligraphy also demonstrate the persistence of the trend for decorative borders at this time. The Rylands’ Persian MS 10, an album completed before 1785–1786AD, features an entwined Arabic calligraphy composition formed from two slogans Tawakkaltu bi-maghfirat al-Muhaymin (I entrust myself to the forgiveness of the Guardian) in black, and Huwa al-Ghafūr Dhū-al-Raḥmah (He is the All-Forgiving Lord of Mercy) in red thuluth script. Two dark indigo blue borders bear delicate silver and gold foliage surrounding a wide margin embellished with vibrant floral flourishes.

Migration to the printed page

In 15th century Germany, Johannes Gutenberg invented the moveable-type printing press. His new technology produced a codex (an ancient manuscript text in book form) that looked like a traditional manuscript with regard to text and margins.

Rubrication – the decoration of letters in coloured inks – was added by hand to the first printed books. As the ability of printers to produce more nuanced illustrations accelerated, the decorated border survived and thrived. Indeed, its importance as part of the aesthetic in terms of how a book should look to an early modern reader drove forward innovations in technology.

The Blackburn Museum’s collection of early printed books is full of examples of the new technology of print accommodating the decorative frame.

Falling in and out of favour

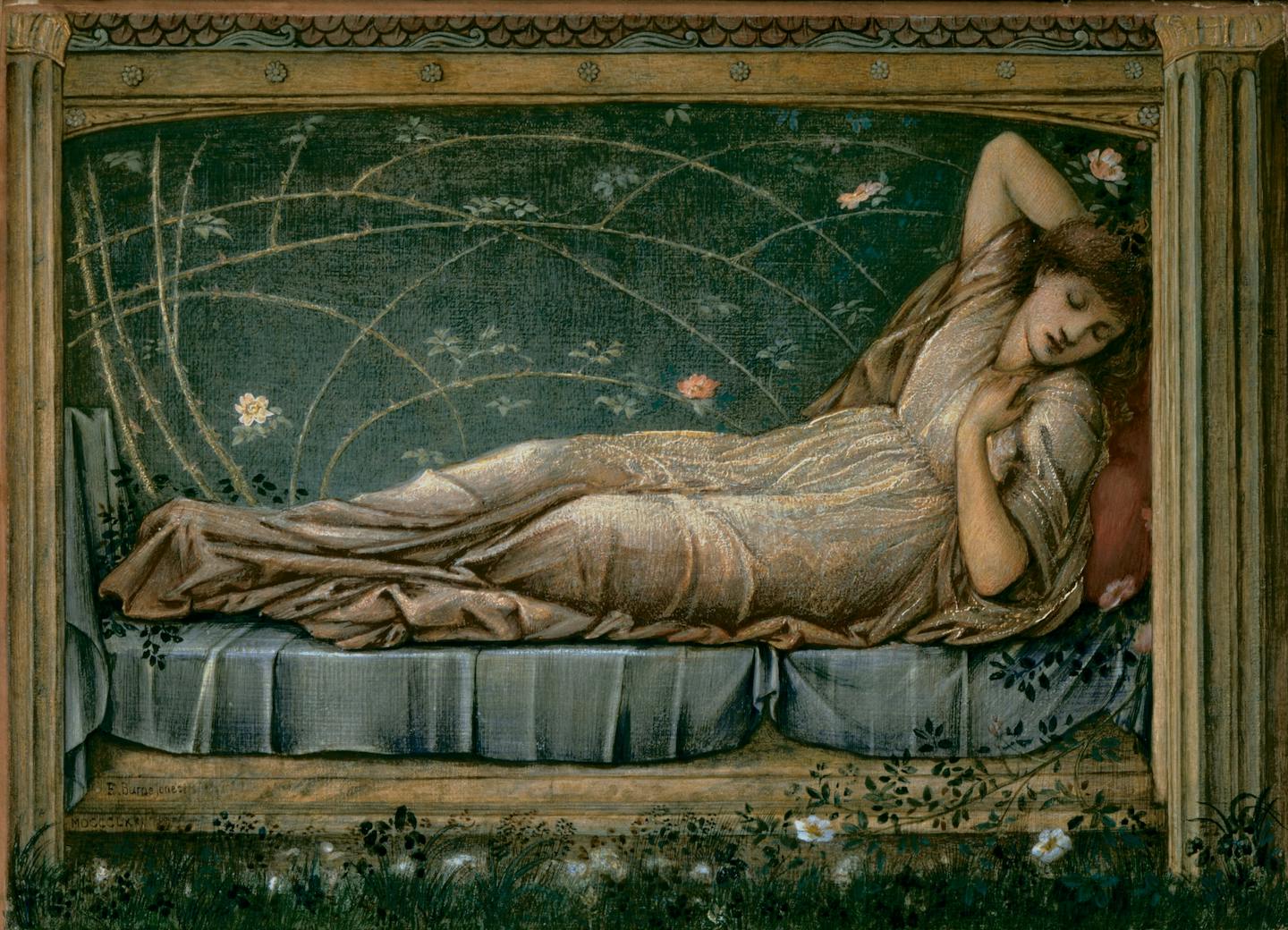

The decorated frame fell out of favour in the 16th and 17th centuries. For western European readers it began to appear old fashioned. But it returned during the Industrial Revolution, thanks to the work of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Pre-Raphaelite artists reached back to the medieval period for their inspiration as well as artistic practice. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris, Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Arthur Hughes and their associates set out to reject the values and industrial production of the 19th century. Medieval narratives found new audiences in Pre-Rapahelite art such as Arthur Hughes’ Sir Galahad, the Quest for the Holy Grail. In the subsequent Arts and Crafts Movement, books, ceramics, textiles and furniture were produced with minimal mechanical intervention. The medieval decorative frame thrived across various media.

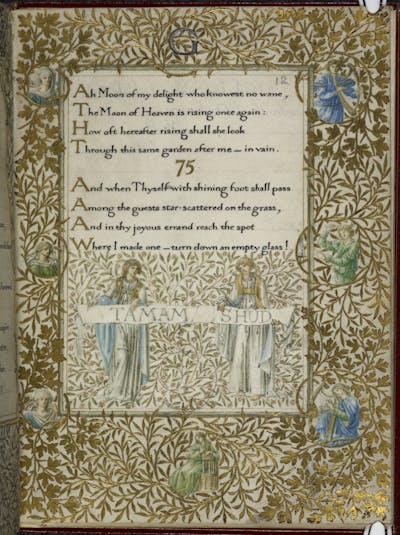

William Morris’ hand-written copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam provides a compelling example of the after-life of the medieval margin. On each page, the text is surrounded by a lush decorated border which is punctuated by cameos that were designed by Burne-Jones and painted by Charles Fairfax Murray.

The Nature of Gothic gives visitors the opportunity to compare the work of medieval masters of decorative art with the work produced by the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Contemporary artist Jamie Holman and ceramicist Nehal Aamir also contribute modern interpretations of the decorated frame.

The result is a celebration of the verdant decorative frames which twist and turn through time, illuminating art of both the past and present.

The Nature of Gothic is at the Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery from September 13 to December 13.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

With thanks to Jake Benson for the translation of Persian 10.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Cynthia Johnston, School of Advanced Study, University of London

Read more:

- Edinburgh Festival: ten of the best art shows to see this summer

- Flowers at London’s Saatchi Gallery: this exploration of flora in history and contemporary culture smells as good as it looks

- Want to understand the history of European culture? Start with the Minoans, not the Ancient Greeks

Cynthia Johnston is employed by The Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. She receives funding from Arts Council England. This exhibit has been supported by major loans from the British Library, the John Rylands Library and Research Centre, Manchester Art Gallery and the Liverpool Museums Trust among others.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Colorado Springs Gazette

Colorado Springs Gazette The Daily Sentinel

The Daily Sentinel Gothamist

Gothamist New York Post Video

New York Post Video AlterNet

AlterNet Columbia Daily Tribune Sports

Columbia Daily Tribune Sports Daily Kos

Daily Kos The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast The Tonight Show

The Tonight Show Political Wire

Political Wire