It’s hard to fathom that 25 years have passed since Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang was published to such acclaim. A glance at the novel’s entry in the AustLit database gives a sense of the phenomenon. It has gone through 15 editions, won 17 awards – including the Booker Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize – and been the subject of more than 200 reviews and articles. It has been translated into 28 languages and regularly finds itself on must-read lists of Australian novels.

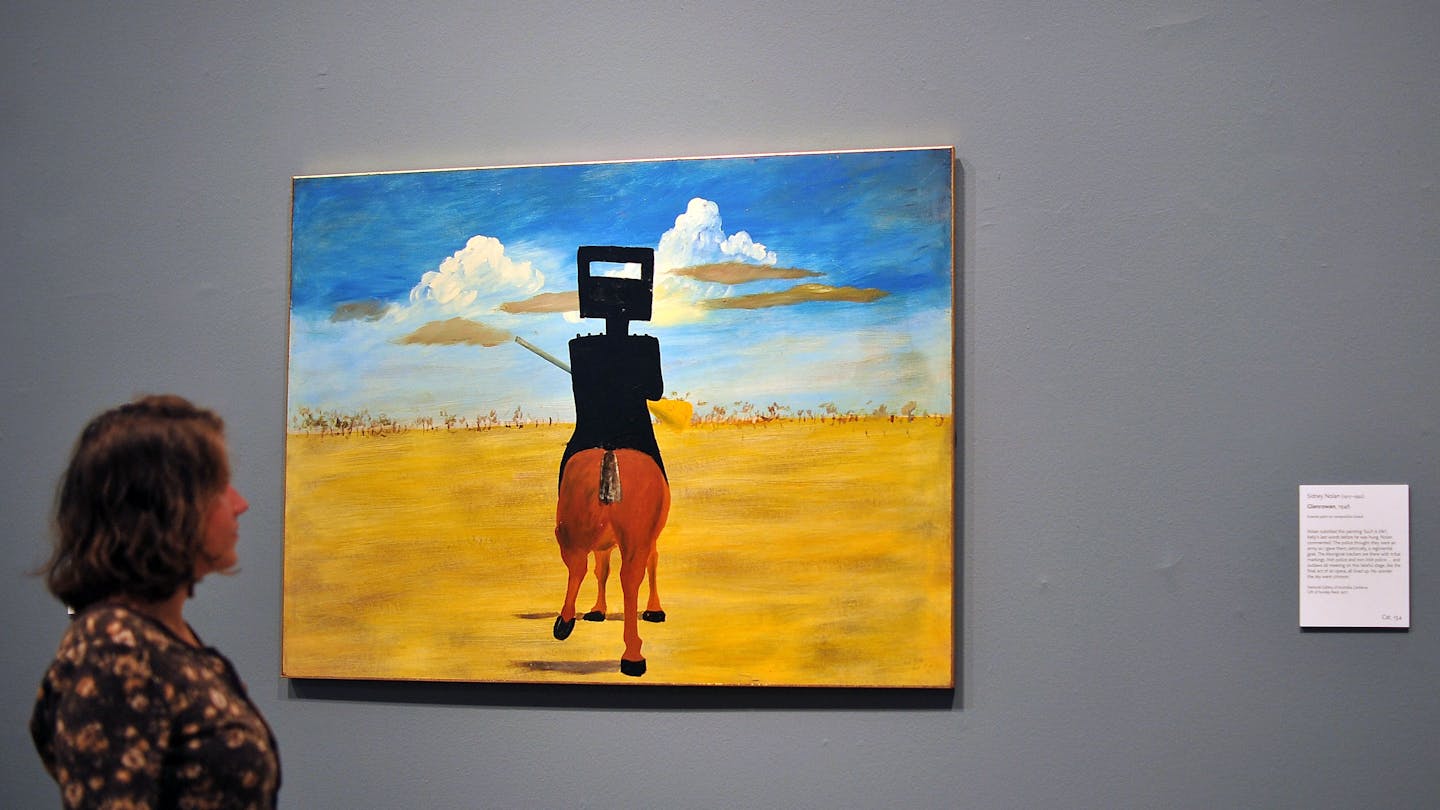

Even before Carey’s novel, Ned Kelly was a cultural icon – a beloved (by some) rogue and outlaw, with a status both historical and mythological. His story was well known; his life had been subject to numerous treatments, fictional and non-fictional, across a range of media, including Sidney Nolan’s powerful series of paintings.

Carey’s novel gives a sense of the extent of Kelly’s popularity – or at least notoriety – and the widespread sympathy he garnered. What makes his rendering special, though, is its sustained use of the vernacular. Inspired by the poetic power of Ned Kelly’s manifesto, the Jerilderie Letter, Carey produced a novel written in Kelly’s voice, with such eloquence that it becomes a masterclass in mimicry.

The novel’s central and clever conceit is that True History of the Kelly Gang is a manuscript of Kelly’s journals written to his daughter. The “stained and dog-eared papers” had been stolen, rediscovered, and brought to the “Melbourne Public Library”. The novel comprises a series of numbered parcels of text, framed by cataloguing descriptions of the kind that might be used by an archivist or librarian.

Much of the novel follows and draws on known people and events from historical records. Carey is careful to include a statement of sources. But he also incorporates sweeping themes of love and betrayal, honour and justice, oppression and resistance, and the old chestnut of mateship. The story explores moral ambiguity – what happens when otherwise decent people find themselves at the mercy of an unjust system over which they have little control; it is also, as John Kinsella has pointed out, thoroughly Oedipal.

True History of the Kelly Gang recounts what is known about Kelly. Like his historical counterpart, Carey’s fictional Ned Kelly is the third of eight children born to poor Irish parents: John “Red” Kelly, a transported convict, and Eileen Quinn. The novel describes his childhood in rural Victoria, his rescue of a drowning boy, the green sash he receives as a reward, and his association with the bushranger Harry Power.

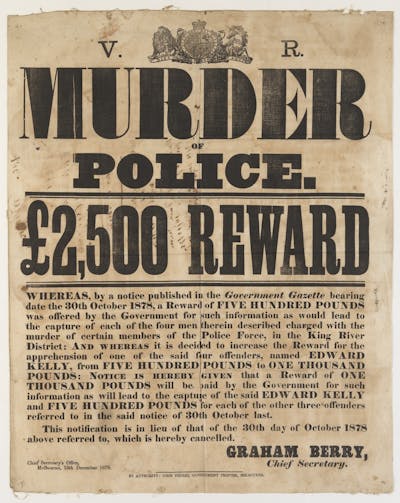

Early convictions lead to time in prison as a mere teenager in the 1870s. Then, in 1878, Kelly attacks Constable Fitzpatrick, who had arrested his brother, Dan. Warrants are issued for the arrest of both Kelly brothers and their mother Eileen. Eileen is imprisoned and Ned and Dan go into hiding. Later, they are joined by Joe Byrne and Steve Hart.

The novel charts the gang’s ambush and killing of three police officers at Stringybark Creek in 1878, followed by bank robberies at Euroa and Jerilderie. The last defiant stand takes place at the siege of Glenrowan in June 1880 in the gang’s now famous armour, before Kelly’s trial, conviction and execution.

The Jerilderie Letter

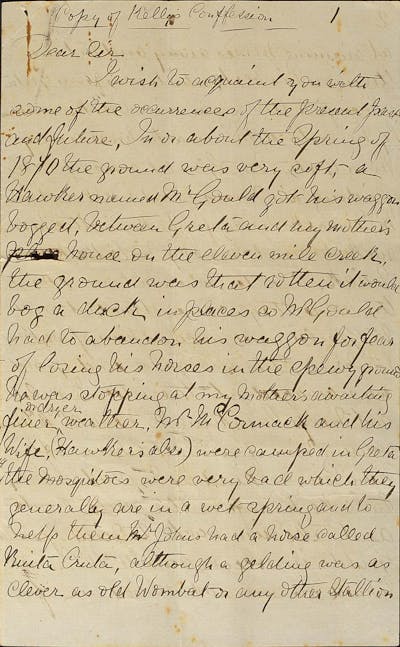

Then there is the historical artefact – the Jerilderie Letter – that so inspired Carey when he first read it.

While holding up the bank at Jerilderie in February 1879, Ned Kelly demanded to see the printer of the local newspaper. He wanted him to publish a 56-page manuscript, a manifesto of sorts, that raged about his family’s unjust treatment at the hands of the police. The manuscript called for justice for poor settlers and selectors in the face of police corruption, government neglect and squatters’ greed.

Most likely dictated to Joe Byrne, the Jerilderie Letter has, like the novel it inspired, little paragraphing or punctuation. Some parts of it find their way into True History of the Kelly Gang.

Although a bank clerk offered to pass on the manuscript, he instead turned it in to Victorian police. The Jerilderie Letter was considered so incendiary that its publication was suppressed until 1930. As scholar Paul Eggert argues, it was “meant to be an intervention in a print culture”. Kelly was attempting to control the narrative. He wanted the truth to be told, the historical record to be corrected.

Carey’s novel retains this motivation, becoming a sustained exercise in legacy-making. In his version, the school teacher, Thomas Curnow, who alerted police to the fact that the train rails had been lifted at Glenrowan, is entrusted with the manuscript. Kelly’s vulnerability to Curnow’s flattery enables the betrayal.

The intended recipient of Ned’s journal is the daughter he never knew, so this is a private and intimate rendering, even as the novel’s framing makes it an archival document of purported historical significance. True History of the Kelly Gang offers not just a sustained voice, but interiority. It conveys Kelly’s thoughts, fears, desires and motivations – or what Carey calls his “soul”.

And because this is a letter to Kelly’s daughter, the reader is invariably on his side. Carey’s Kelly is wise, thoughtful and compassionate, as any parent tries to convince their child they are. There is always a reasonable justification for even his most violent actions – so the reliability of this narrator is questionable.

Carey is not only preoccupied with storytelling at the level of the plot; he is interested in the question of who gets to tell their story and how. He is conscious of the many ambiguous purposes to which stories can be put. The first of many corrupt policemen to appear in the novel, Sergeant O’Neill – himself a malicious and gifted storyteller with an agenda – gives the young Ned a pencil, then attempts to seduce his mother while Ned practises his letters.

The novel’s “voice” evokes oral storytelling, but it is, of course, in print. At this juncture between oral and written storytelling, Carey interrogates the power and presence of orality, as well as the authority of the written word, and the print culture that reproduces and disseminates it.

Print culture has its own logic, and the purity of Kelly’s voice is increasingly diluted and interrupted by other voices and perspectives. The novel incorporates newspaper articles, Mary Hearn’s annotations of them, and Joe Byrne’s account of his boxing match with “Wild” Wright. Even the archivist’s descriptions and the voice of the manuscript’s unnamed collector reveal a story enmeshed with multiple perspectives and framing devices, all of which determine how Kelly’s voice is received and understood.

Fiction, truth and mythmaking

Carey’s “true history” is not a novelist’s attempt to faithfully recreate historical events; it is interested in the relationship between literary and historical reproduction. As Carey says: “My fictional project has always been the invention or discovery of my own country.”

The slippage between invention and discovery is telling. Are they the same process? Mutually exclusive? In tension? Entirely fictionalised elements are woven through Carey’s imaginings of what Ned Kelly thought and felt. Most notably, there is the invention of Kelly’s lover, the Irish-born Mary Hearn, and the birth of his daughter – to whom the novel is addressed.

Through this interplay of truth and fiction, Carey’s novel participates in a form of mythmaking. Indeed, it is a novel about mythmaking, as much as it is about the myth of the iconic bushranger himself.

And, over time, the writing of the novel has become mythologised. In a recent article journalist Melanie Kembrey asserts that the “origin story of True History of the Kelly Gang is almost mythic in itself”. Carey delights in retelling the story of how the novel came to be – how, under the wing of older Australian cultural journos, he was first introduced to and enchanted by Nolan’s paintings, how he was blown away by the poetry of the Jerilderie Letter and carried it around with him, waiting for the story to emerge. When Nolan’s work was exhibited in New York, Carey recalled,

One by one, I brought my new Manhattan friends uptown and walked them around the 27 paintings as if they were the stations of the Cross. I explained why, while we had no Thomas Jefferson, our imaginary founding father was a convicted murderer named Ned.

But what does it mean to have a historical figure as an “imaginary” founding father? And in what sense does Ned fulfil this role?

It is well known that the Kelly family was Irish, but one of the things I was most struck by in rereading the novel is the centrality of Irishness. Both foundational and oppositional, Irishness pervades the novel: a means of forging a “distinctive Australian identity”, an identity “born in Irishness protesting against the extremes of Englishness”, as historian Patrick O’Farrell once argued.

In the novel, the young Ned is raised on a diet of Irish myths — “the stories of Conchobar and Dedriu and Mebd the tale of Cuchulainn” — and Irish curses and superstitions, including the Banshee, who “were thriving like blackberry in the new climate”. These stories are a source of fear and respect.

Mary Hearn, the mastermind behind the well-oiled bank robberies, is a plucky Irish woman who sets the “colonials” straight. When Dan Kelly and Steve Hart appear dressed in women’s clothing (the much-discussed cross-dressing scenes), she faints. Steve thinks he is emulating the fictional Sons of Sieve, whom he reveres as an Irish resistance movement. Mary’s visceral reaction reveals otherwise — the Sons of Sieve had engaged in violent campaigns of terror against the poor, becoming the oppressors they sought to overthrow.

The novel, then, is clearly aware of the power of stories and the ways they can become distorted and misused. Yet it does not seem to heed what it knows: that myths can be seductive and dangerous, and the grounds for ongoing tyranny.

If this is a novel of national mythmaking, it is also one of erasure. Kelly lived at a time when the Irish were brutally oppressed, in both Ireland and Australia. Carey’s novel was written and published at a time of Australian national reckoning, after the High Court’s Mabo judgement and a painful debate about a national apology in the wake of the Bringing Them Home report into the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families. What some might call the failed official Reconciliation process, instigated in response to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, came to an end in 2001.

Published at the dawn of the new millennium, True History of the Kelly Gang could be read as reinstating a victimised and innocent white settler subjectivity that was well past its use-by date. It is a thoroughly white story. The almost complete absence of Indigenous characters – except as feared, shadowy figures on the periphery – and the boldness with which Carey’s Kelly claims stolen land as his own through recourse to Irish history and myth obfuscates the fact that the country Carey claims for Kelly was already deeply storied.

The novel thus subscribes to what Wiradyuri poet and critic Jeanine Leane calls the settler mythscape. And for all their historical accuracy, the racialised epithets are, to this reader, jarring – though not as jarring as critic Peter Craven’s recent homage, which hails the novel as “a sustained act of literary genius in the face of history, forged in the fire of truth-telling”.

Literary genius it may be, but “truth-telling”? To see a term that has come to hold such charged and ambivalent meanings used in a context where, a quarter of a century later, the nation still seems unable to face the truth of the past and the injustices that flow from it seems, to me, plainly wrongheaded.

We live at a time when inequality is growing and speaking out against all manner of injustice has become increasingly criminalised. There is, at the same time, a perturbing pattern of growing white nationalism, fuelled by grievance with a violent conspiratorial edge.

As I write, a police hunt is underway following the killing of two policemen; the fugitive, an anti-government conspiracy theorist, remains on the run in the Victorian high country. Some are referring to the alleged murderer as a modern-day Ned Kelly, and he clearly has sympathisers.

The implications of the Kelly myth that so enamoured Carey – what it nurtured, what it refused to see, and the legacy it built – seem to have come full circle in the most tragic of ways.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Maggie Nolan, The University of Queensland

Read more:

- Papua New Guinea has played an important role in Australian history – it’s time we acknowledged that

- The decision to close Meanjin misunderstands its wider importance. Australian culture deserves better

- Why the Eureka flag and other ‘alternative national flags’ were claimed by anti-immigration protesters

Maggie Nolan receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CBC News World

CBC News World AlterNet

AlterNet RadarOnline

RadarOnline NFL Buffalo Bills

NFL Buffalo Bills New York Post Video

New York Post Video Raw Story

Raw Story