Recognition of a Palestinian state is likely to dominate proceedings at the U.N. beginning Sept 23. 2005, when world leaders will gather for the annual general assembly.

Of the 193 existing U.N member states, some 147 already recognize a Palestinian state. But that number is expected to swell in the coming days, with several more countries expected to officially announce such recognition. They include Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Portugal and the U.K. – although Britain says it won’t support statehood if Israel takes steps to alleviate the plight of Palestinians in Gaza.

That a host of Western nations are adding their names to the near-universal list of Global South countries that already recognize a Palestinian state is a major diplomatic win for the cause of an independent, sovereign and self-governed nation for Palestinians. Conversely, it is a massive diplomatic loss for Israel – especially coming just two years after the West stood shoulder to shoulder with Israel following the Oct. 7 attack by Palestinian militant group Hamas.

As a scholar of modern Palestinian history, I know that this diplomatic moment is decades in the making. But I am also aware that symbolic diplomatic breakthroughs on the issue of Palestinian statehood have occurred before, only to prove meaningless in the face of events that make statehood less likely.

The non-state reality

The fight for Palestinian statehood can be traced back to at least 1967. Over the course of a six-day war against a coalition of Arab states, Israel conquered and expanded its military control over the remainder of what was historic Palestine – a stretch of land that extends from the Jordan River in the east to the Mediterranean Sea in the west.

At the war’s conclusion, Israel had taken control of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip.

Unlike after the 1948 war that led to its independence, Israel opted not to extend Israeli citizenship to Palestinians living in the newly conquered areas. Instead, the Israeli government began to rule over Palestinians in these occupied territories through a series of military orders.

These orders controlled nearly every aspect of Palestinian life – and many remain in effect today. For example, if a Palestinian farmer wants to harvest his olive trees near a Jewish settlement in the West Bank, they need a permit. Or if a Gazan worker wants to work inside Israel, they need Israeli permission. Even praying in a mosque or church in East Jerusalem is dependent on obtaining a permit.

This permit system served as a constant reminder to Palestinians living in the occupied territories that they lacked control over their own daily lives. Meanwhile, Israeli authorities tried to squash the idea of Palestinian nationhood through policies such as outlawing public displays of the Palestinian flag. That, and other expressions of Palestinian national identity in the occupied territories, could result in up to 10 years in prison.

Such policies fit a belief, expressed in 1969 by then Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, that there was “no such thing in this area as Palestinians.”

The rise of Palestinian nationalism

Around the same time that Meir made that comment, Palestinians started organizing around the idea of statehood.

Although the idea had been floated before, statehood was codified into official doctrine in a resolution in February 1969 in Egypt. It occurred during a session of the Palestine National Council, the legislative body of the Palestine Liberation Organization, which formed in 1964 as the official representative of Palestinians in the occupied territories.

That resolution called for a free, secular democratic state in Palestine – including all of the State of Israel – in which Muslims, Christians and Jews would all have equal rights.

From that moment on, the Palestinian struggle against Israeli occupation took twin paths: diplomatic pressure and armed resistance.

But events on the ground undermined the idea of a single state for all along the lines envisioned by the Cairo resolution.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War’s inconclusive ending opened the door to greater diplomacy between Israel and the Arab states. Egypt and Israel decided that diplomacy would help them achieve their aims, culminating in the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty of 1979. But the treaty also left the Palestinians without unified Arab support.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1970s, the Israeli occupation deepened and entrenched with the building of Israeli settlements, especially in the West Bank.

The PLO responded in 1974 by issuing what became known as the 10-Point Plan, where they pivoted to seeking the establishment of a national authority in any part of historic Palestine that could be liberated.

It was, in effect, a way of threading the needle: It signaled to moderates that the PLO was adopting a more gradualist position, while also telling the group’s rejectionist front – which opposed peace negotiations with Israel – that they were not giving up completely on the idea of liberating all of Palestine.

Then in 1988 – a year into the first Palestinian intifada, or uprising – the PLO unilaterally declared Palestinian independence on the territories occupied in 1967.

The move was largely symbolic – the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem were still under occupation, and the PLO was then in exile in Tunisia.

But it was nonetheless significant. It represented the bringing together of Palestinians in exile – most of whom were from towns and villages that were now part of the State of Israel – with Palestinians in the occupied territories.

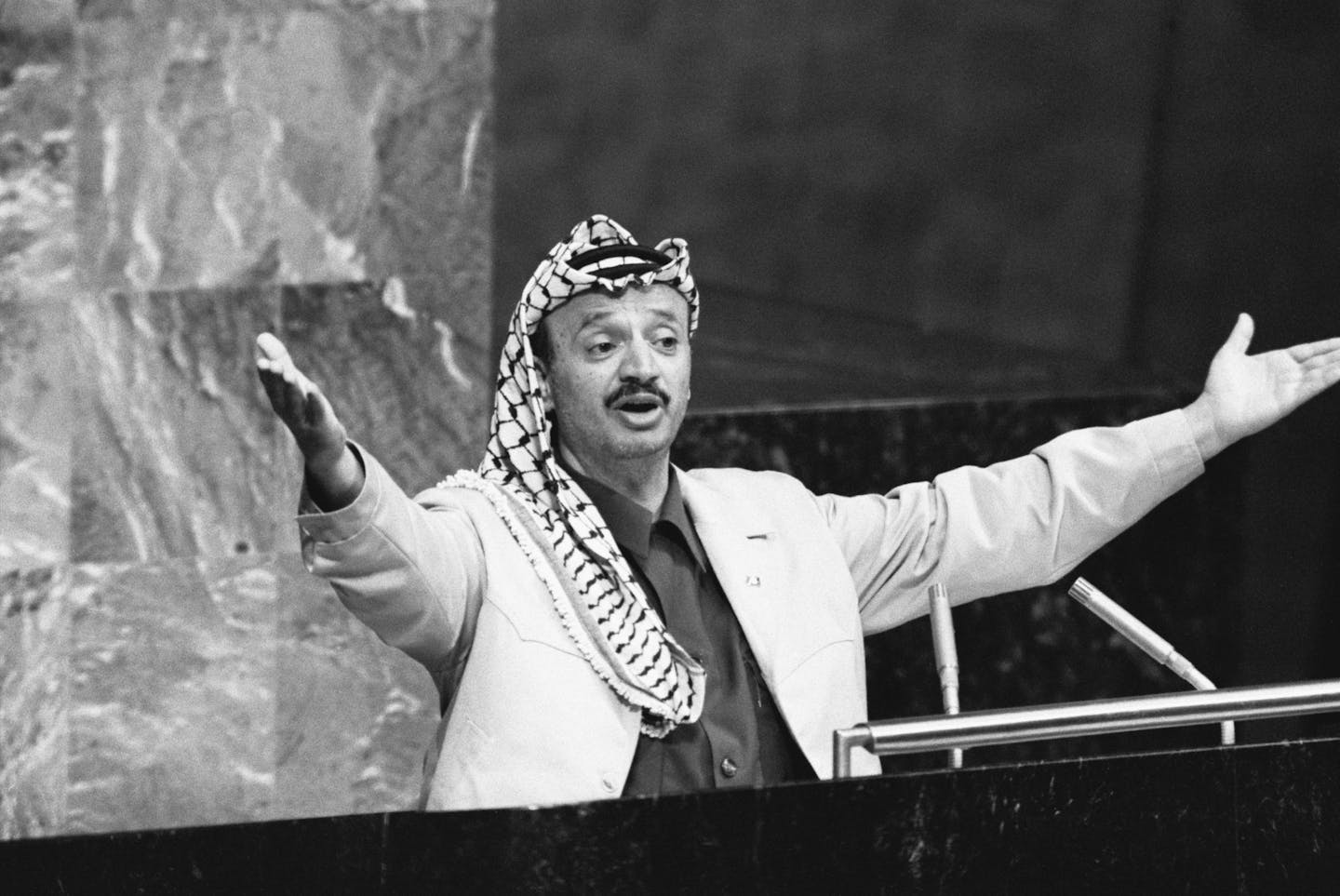

The declaration itself was written by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who grew up inside Israel, and declared by Yasser Arafat, the PLO leader in exile.

It was also a moment of tremendous hope and possibility for Palestinians. What most Palestinians wanted was for the international community to recognize them as a national body, deserving of a seat at the table with other nation-states.

Compromise and rejection

Yet at the same time, many Palestinians saw the declaration as a huge compromise. The West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem comprise about 22% of historic Palestine. So the declaration effectively meant that Palestinians were giving up on the other 78% of what they saw as their land.

Reaction from the international community to the PLO’s declaration was split. Many formerly colonized countries of the Global South recognized Palestinian independence right away. By the end of the year, some 78 countries had issued statements recognizing Palestine as a state.

Israel rejected it outright, as did United States and most Western nations.

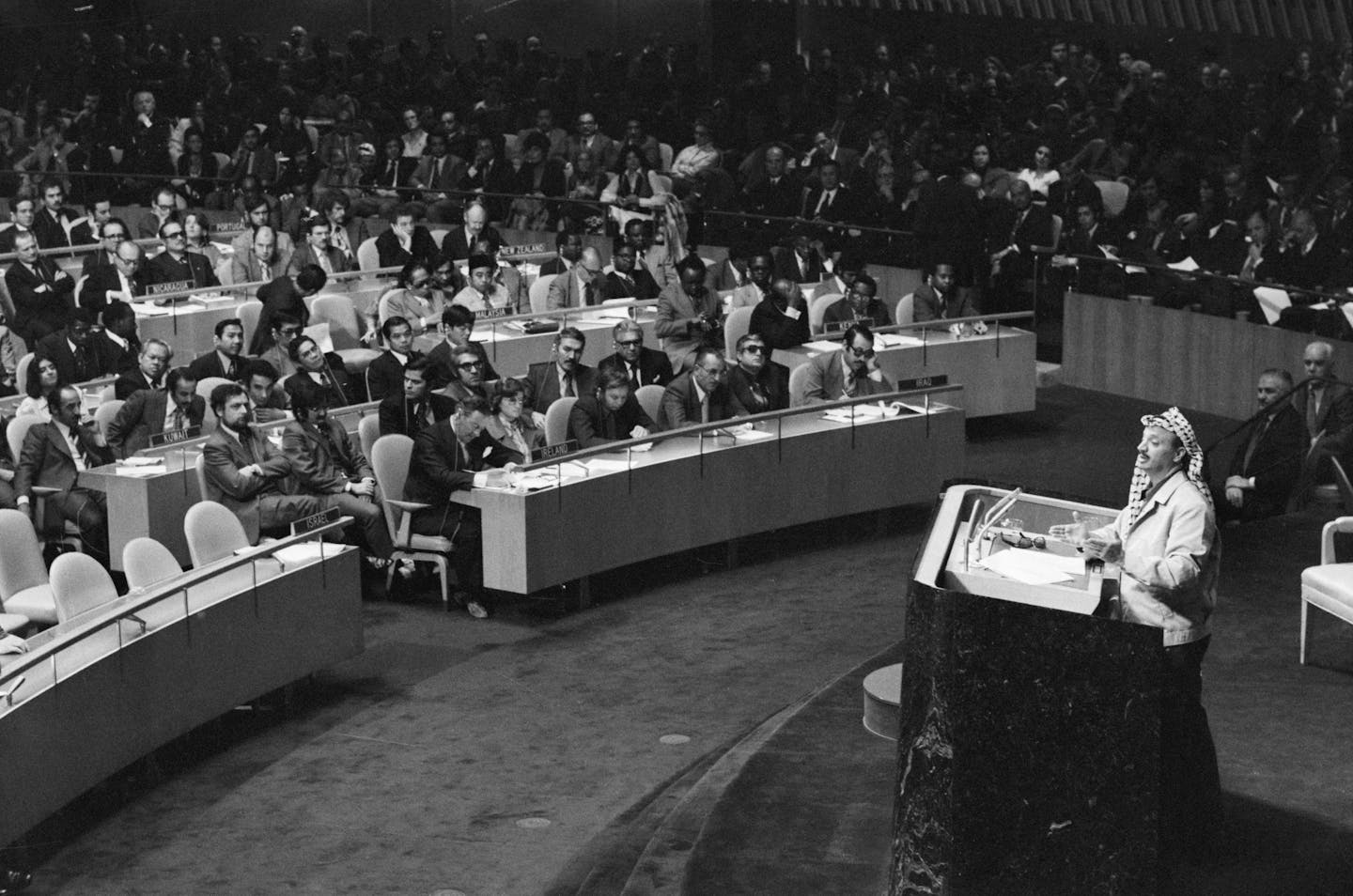

Such was Washington’s opposition that the U.S. denied Arafat a visa ahead of his planned address to the United Nations at its New York City headquarters. As a result, the December 1988 meeting had to be moved to Geneva.

While refusing to accept Palestinian statehood, the U.S. and Israel did begin to recognize the PLO as a representative body of the Palestinian people. This was part of the Oslo Accords – a diplomatic process that many believed would outline a road map for an eventual two-state solution.

While some Palestinians saw the Oslo Accords as a diplomatic breakthrough, others were more skeptical. Prominent Palestinians, including Darwish and Palestinian-American professor Edward Said, believed that Oslo was a poison pill: While framed as a step toward a two-state solution, the agreement said nothing about a Palestinian state in the interim. It only said that Israel would recognize the PLO as a representative of the Palestinian people.

In reality, the Oslo Accords have not lead to statehood. Rather, they created a system of fragmented autonomy under the newly created Palestinian Authority that, though meant to be interim, has in effect become permanent.

The Palestinian Authority was allowed only limited powers and deprived of real independence. While it had some say over schooling, health care and municipal services, Israel maintained control of Palestinian land, resources, borders and the economy. That remains true today.

Renewed push for statehood recognition

Disillusionment over the Oslo Accords contributed to the second, far more violent, intifada from 2000 to 2005.

Mahmoud Abbas, the leader of the Palestinian Authority after Arafat, responded by pushing again for international recognition for statehood.

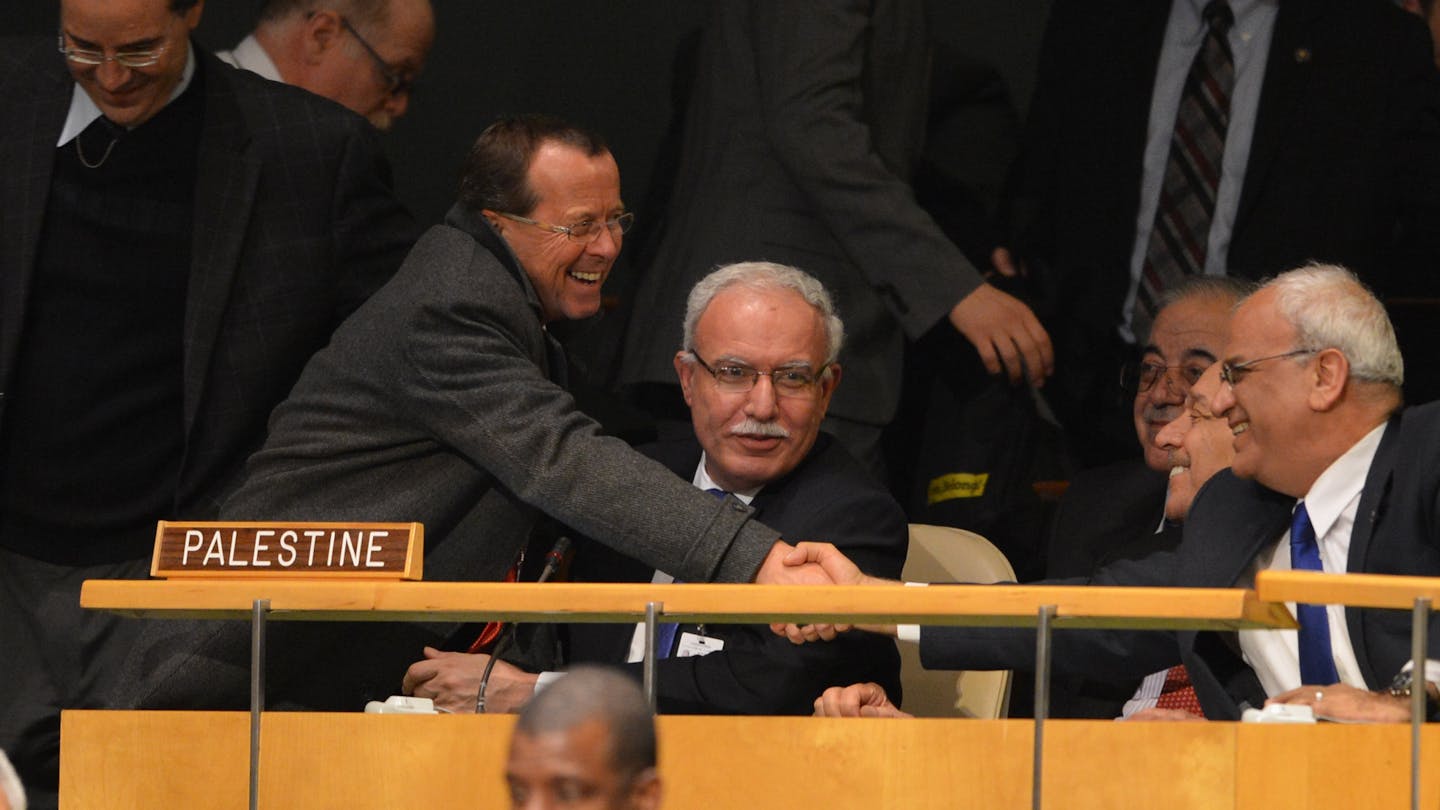

And in 2012, the U.N. General Assembly voted to upgrade Palestine’s status, elevating it from a “nonmember observer” to a “nonmember observer state.”

In theory, this meant Palestinians now had access to international bodies, like the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice.

But any meaningful change in the status of Palestinian sovereignty would need to come through the U.N. Security Council, not the U.N. General Assembly.

The U.S. remains opposed to Palestinians gaining statehood independent of the Oslo process. So long as the U.S. has a veto on the Security Council, achieving a truly sovereign Palestinian state will likewise be off the table. And that remains the case, regardless of what individual members – even fellow Security Council members like France and the U.K – do.

In fact, many Palestinians and other critics of the status quo say Western nations are using the issue of Palestinian statehood to absolve them from the far more challenging diplomatic task of holding Israel accountable for what a U.N. body just described as a genocide in Gaza.

This article is based on a conversation between Maha Nassar and Gemma Ware for The Conversation Weekly podcast.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Maha Nassar, University of Arizona

Read more:

- From resistance to intifada to recognition: the origins of an independent Palestinian state – podcast

- Israel’s killing of journalists follows a pattern of silencing Palestinian media that stretches back to 1967

- Israel is committing genocide in Gaza, says UN commission. But will it make any difference?

Maha Nassar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

New York Post

New York Post Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News AlterNet

AlterNet Raw Story

Raw Story Reuters US Politics

Reuters US Politics Vogue Shopping

Vogue Shopping Nicki Swift

Nicki Swift