Three converging events in the 1970s – the Watergate scandal, the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from the Vietnam War and revelations that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had abused his power to persecute people and organizations he viewed as political enemies – destroyed what formerly had been near-automatic trust in the presidency and the FBI.

In response, Congress enacted reforms designed to ensure that legal actions by the Department of Justice and the FBI, the department’s main investigative arm, would be insulated from politics. These included stronger congressional oversight, a 10-year term limit for FBI directors and investigative guidelines issued by the attorney general.

Some of these measures, however, were tenuous. For example, Justice Department leaders could alter FBI investigative guidelines at any time.

Donald Trump’s first presidential term seriously tested DOJ and FBI independence – notably, when Trump fired FBI Director James Comey in May 2017. Trump claimed Comey mishandled a 2016 probe into Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton’s private email server, but Comey also refused to pledge loyalty to the president.

Now, in Trump’s second term, prior guardrails have vanished. The president has installed loyalists at the DOJ and FBI who are dedicated to implementing his political interests.

As a historian of the FBI, I recognize the FBI has had only one other overtly political director in the past 50 years: L. Patrick Gray, who served for a year under President Richard Nixon. Gray was held accountable after he tried to help Nixon end the FBI’s Watergate investigation. Whether Trump’s current director, Kash Patel, has more staying power is unclear.

After Hoover

Ever since Hoover’s death in 1972, presidents have typically nominated independent candidates with bipartisan support and law enforcement roots to run the FBI. Most nominees have been judges, senior prosecutors or former FBI or Justice Department officials.

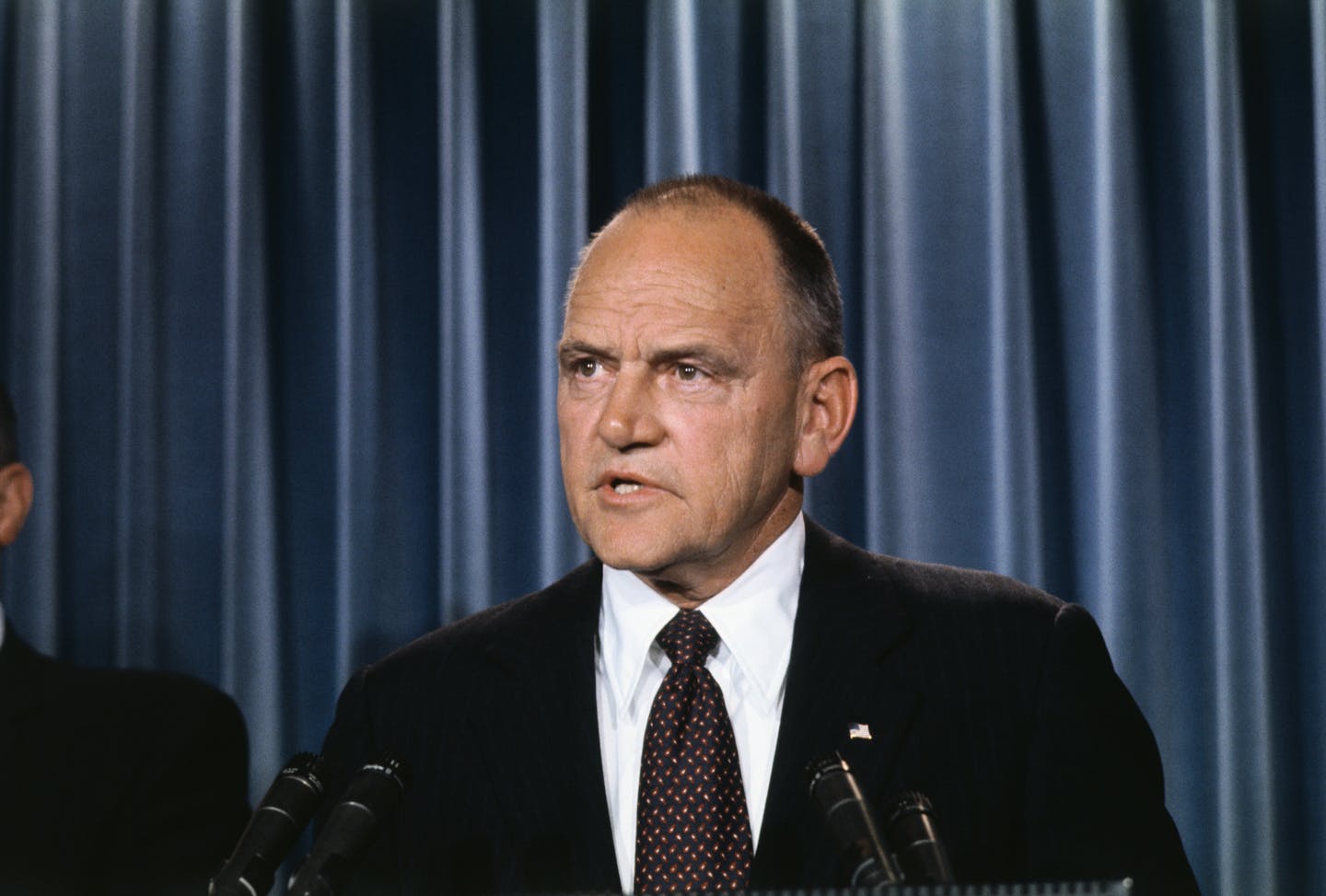

While Hoover publicly proclaimed his FBI independent of politics, he sometimes did the bidding of presidents, including Nixon. Still, Nixon felt that Hoover had not been compliant enough, so in 1972 he selected Gray, a longtime friend and assistant attorney general, to be Hoover’s successor.

Gray took steps to move the bureau out of Hoover’s shadow. He relaxed strict dress codes for agents, recruited female agents and pointedly hired people from outside the agency – who were not indoctrinated in the Hoover culture – for administrative posts.

Gray asserted his authority with blunt force. FBI agents at field offices and at headquarters who resisted Gray’s power were censured, fired or transferred. Other senior officials opted to leave, including the bureau’s top fraud expert, cryptanalyst and skyjacking expert, and the head of its Crime Information Center.

Agents regarded these moves as a purge, and press reports claimed that bureau morale was at an all-time low, charges that Gray denied. According to FBI Associate Director Mark Felt, who became Gray’s second in command, 10 of 16 top FBI officials chose to retire, most of them notable Hoover men.

Gray surrounded himself with what journalist Jack Anderson called “sharp, but inexperienced, modish, young aides.” FBI insiders called these new hires the “Mod Squad,” a reference to the counterculture TV police series.

Gray helps Nixon

In contrast to Hoover, who had rarely left FBI headquarters and publicly avoided politics, Gray openly stumped for Nixon in the 1972 campaign. He was so rarely spotted at FBI headquarters that bureau insiders dubbed him “Two-Day Gray.” At the request of Nixon aide John Ehrlichman, Gray told field offices to help Nixon campaign surrogates by providing local crime information.

Gray cooperated with Nixon to stymie the FBI’s investigation of the 1972 Watergate break-in and the ensuing cover-up. He provided raw FBI investigative documents to the White House and burned documents from Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt’s White House safe.

When Nixon had CIA Deputy Director Vernon Walters ask Gray, in the name of national security, to halt the FBI’s investigation, Felt and other agency insiders demanded that Gray get this order in writing. The White House backed down, but Nixon’s directive had been recorded. That tape became the so-called “smoking gun” evidence of a Watergate cover-up.

Felt, in classic Hoover fashion, then leaked information to discredit Gray, hoping to replace him. Gray resigned in disgrace.

While Felt never got the top job, he is now remembered as the prized anonymous source “Deep Throat,” who helped Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in their Pulitzer Prize-winning Watergate investigation. But it was internal FBI resistance, from Felt and agents at lower levels, that led to Gray’s departure.

Political from the start

Campaigning in 2024, Donald Trump vowed to “root out” his political opponents from government. Realizing he was a target because of his investigation of the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, FBI director Christopher Wray, whom Trump had nominated in 2017, resigned in December 2024 before Trump could fire him.

In Wray’s place Trump nominated loyalist Kash Patel, a lawyer who worked as a low-level federal prosecutor from 2013 to 2016 and then as a deputy national security appointee during Trump’s first term.

Patel publicly supported Trump’s vow to purge enemies and claimed the FBI was part of a “deep state” that was resistant to Trump. Patel promised to help dismantle this disloyal core and to “rebuild public trust” in the FBI.

Even before Patel was confirmed on Feb. 20, 2025, in an historically close 51-49 vote, the Justice Department began transferring thousands of agents away from national security matters to immigration duty, which was not a traditional FBI focus.

Hours after taking office, Patel shifted 1,500 agents and staff from FBI headquarters to field offices, claiming that he was streamlining operations.

Patel installed outsider Dan Bongino as deputy director. Bongino, another Trump loyalist, was a former New York City policeman and Secret Service agent who had become a full-time political commentator. He embraced a conspiracy theory positing the FBI was “irredeemably corrupt” and advocated “an absolute housecleaning.”

In February, New York City Special Agent in Charge James Dennehy told FBI staff “to dig in” and oppose expected and unprecedented political intrusions. He was forced out by March.

Patel then used lie-detector tests and carried out a string of high-profile firings of agents who had investigated either Trump or the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. Some agents who were fired had been photographed kneeling during a 2020 racial justice protest in Washington, D.C. – an action they said they took to defuse tensions with protesters.

In response, three fired agents are suing Patel for what they call a political retribution campaign. Ex-NFL football player Charles Tillman, who became an FBI agent in 2017, resigned in September 2025 in protest of Trump policies. Once again, there are assertions of a purge.

Will Patel be held accountable?

Patel’s actions as director so far illustrate that he is willing to use his position to implement the president’s political designs. When Gray tried to do this in the 1970s, accountability still held force, and Gray left office in disgrace. Gray participated in a cover-up of illegal behavior that became the subject of an impeachment proceeding. What Patel has done to date, at least what we know about, is not the equivalent – so far.

Today, Patel’s tenure rests solely upon pleasing the president. If formal accountability – a key element of a democracy – is to survive, it will have to come from Congress, whose Republican majority has so far not exercised its power to hold Trump or his administration accountable. Short of that, perhaps internal resistance within the administration or pressure from the public and the media might serve the oversight function that Congress, over the past eight months, has abrogated.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Douglas M. Charles, Penn State

Read more:

- Trump’s targeting of ‘enemies’ like James Comey echoes FBI’s dark history of mass surveillance, dirty tricks and perversion of justice under J. Edgar Hoover

- Politicians may rail against the ‘deep state,’ but research shows federal workers are effective and committed, not subversive

- Comey isn’t the first FBI director to keep memos on a president

Douglas M. Charles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

TechCrunch

TechCrunch AlterNet

AlterNet Raw Story

Raw Story NFL Indianapolis Colts

NFL Indianapolis Colts CNN

CNN DoYouRemember?

DoYouRemember? America News

America News