In the Marshall Islands, where the land averages only 7 feet (2 meters) above sea level, people are acutely aware of climate change.

Their ancestors have lived on this string of Pacific islands for thousands of years. But as sea level rises, storms more easily flood communities and farmland with saltwater. Warming ocean water has triggered mass coral-bleaching events, harming habitats that are important for both tourism and fish that the islands’ economy relies on.

If the world fails to rein in the greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change, studies suggest low-lying islands like these could be uninhabitable within decades.

Climate change isn’t just a problem for islands. Countries worldwide are experiencing intensifying storms, dangerous heat waves and rising seas as global temperatures rise.

Yet, after 30 years of international climate talks, 10 years of a global treaty promising to keep temperatures in check, and trillions of dollars in damage, the world is still not on track to stop rising global temperatures. Greenhouse gas emissions were at record highs in 2024, and it was Earth’s hottest year on record.

I study the dynamics of global environmental politics, including the United Nations climate negotiations. And I and my lab have been tracking countries’ latest climate pledges – known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs – to see which countries have stepped up their efforts, which have slid back and who has ideas that can deliver a safer world for everyone.

While the Trump administration has been pressuring countries to back away from their climate commitments – and succeeded in delaying an International Maritime Organization vote on a global plan to tax greenhouse gas emissions from shipping after threatening other counties with sanctions, visa restrictions and port fees if they supported it – many countries are still pressing ahead.

Trump agitates, but many countries are steadfast

U.S. President Donald Trump, whose administration came into office vowing to eliminate climate regulations and boost the fossil fuel industry, derided concerns about climate change in his Sept. 23, 2025, speech to the U.N. General Assembly. He called climate change the “greatest con job ever perpetuated” and ridiculed green energy and climate science.

Trump’s language no longer surprises world leaders, though. More than 100 other countries announced new climate commitments during a high-level summit a few days later.

China, currently the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, was lauded for hitting its green energy targets five years early. Its rapid expansion of low-cost renewable energy and electric vehicle manufacturing has reduced pollution in Chinese cities while also boosting its economy and expanding the government’s influence around the world.

Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the country’s first absolute emissions reduction goal at the summit, committing to cut its net greenhouse gas emissions by 7% to 10% from peak levels by 2035. China also committed to nearly triple its solar and wind power capacity and expand reforestation efforts.

While advocates and other governments had hoped for a stronger announcement from China, the new goals mark an important shift from the country’s earlier carbon intensity targets, which aimed to decrease the amount of greenhouse gas emissions per unit of economic output but still allowed emissions to grow over time.

The European Union has yet to submit its new commitments, but the group of 27 European countries delivered a letter of intent, saying it would commit to a 66% to 72% collective decrease in net greenhouse gas emissions by 2035 compared with 1990 levels. Europe has seen a swift rise in renewable energy, up sharply since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine put the continent’s natural gas supplies in jeopardy.

The EU has also made waves by extending its carbon pricing rules beyond its borders.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, scheduled to begin in January 2026, will be the first system to charge for the climate impact of imported goods coming into Europe from countries that don’t have carbon prices similar to the EU’s. The measure, meant to even the playing field for EU industries, sets a global precedent for linking carbon emissions to trade.

However, the EU’s climate plans are also facing some headwinds. Its parliament is moving toward softening new corporate sustainability requirements after pressure from companies. And it may face calls from some member countries to delay a new carbon market meant to cut emissions from road transportation and buildings, Politico reported.

The EU has pledged to mobilize up to 300 billion Euros (about US$350 billion) to support the global clean energy transition in developing countries.

The United Kingdom, Japan and Australia submitted their most ambitious targets to date. All three put them on track to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, meaning any greenhouse gases they emit will be offset by projects that avoid carbon emissions or remove carbon from the atmosphere.

In Australia, Queensland’s recent announcement that it would extend existing coal power plant use to the 2030s and 2040s may slow national progress. But Queensland also supports scaling up renewable energy and is still aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050.

Norway committed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 70% by 2035 compared with 1990 levels, which would align with the Paris Agreement goal to keep global emissions below 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). However, it plans to remain a major oil and gas exporter.

Notably, many developing countries also stepped up their commitments.

Brazil pledged a net emissions reduction of 59% to 67% by 2035 and is maintaining its 2050 net-zero target. The government also drew criticism for approving plans for oil exploration near the mouth of the Amazon River.

Free riding and taking cover behind the US

However, while some new climate commitments signal important momentum in the fight against climate change, the tug-of-war between global ambition to slow climate change and strategic self-interests was palpable at the New York summit. The responses to Trump’s remarks revealed both veiled critiques and deceleration of climate action by some governments.

China criticized backsliding by some countries, without naming names.

Brazil used the summit to call out countries that were late in submitting their updated climate commitments. Only about a third had submitted their updated pledges at that point.

While it is difficult to parse out individual country motivations – economic stress, wars and political influence can all play a role – many scholars worry that U.S. backsliding will lead other countries to reduce their climate commitments, and some recent pledges appear to back this up.

Many petroleum-producing countries missed the U.N. pledge deadline. Qatar, which recently gifted the U.S. a jet plane for Trump’s use and has an economy largely bolstered by the oil and gas industry, has not updated its pledge since 2021. The six-member Gulf Cooperation Council’s average emissions reduction target is even lower than Qatar’s, at around 21.6% by 2030.

Similarly, Argentina, among the world’s top holders of shale oil and gas reserves, has not released its updated commitments. Progress on its previous commitment has been undermined by political shifts since President Javier Milei’s election in 2023.

Milei initially vowed to abandon the 2030 agenda entirely and withdraw from the Paris Agreement, though his administration later backtracked. His dismissal of climate change as a “socialist lie” has aligned Argentina closely with Trump, culminating in a recently planned US$20 billion aid package from the U.S. to Argentina and raising questions about whether Argentina’s climate stance reflects genuine policy or geopolitical strategy.

Also noticeably absent are commitments from India, Mexico, South Africa and Saudi Arabia. Angola weakened its climate pledge, citing lack of international funding.

A new way to make climate commitments?

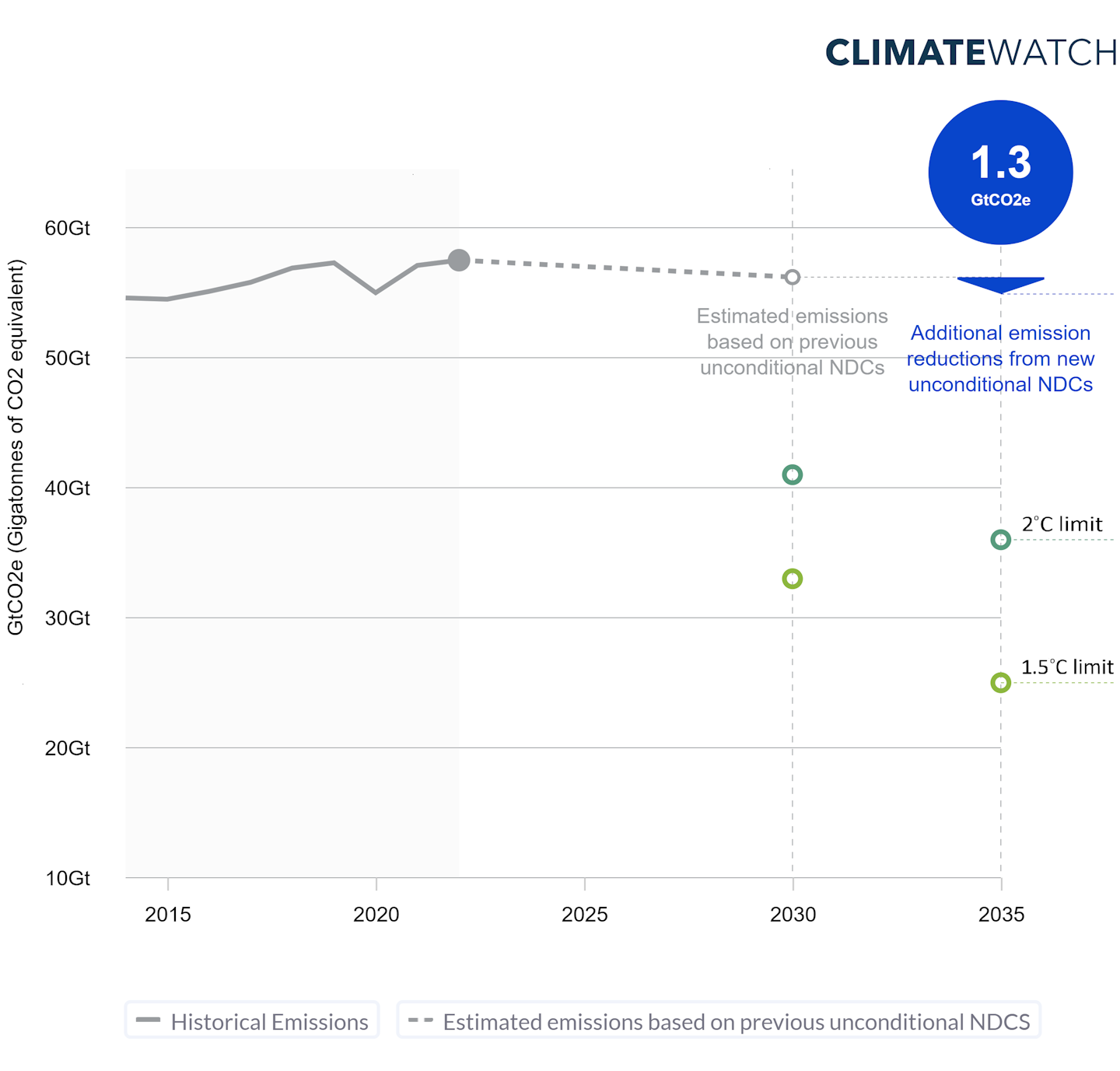

While many countries are promising progress to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the commitments formally submitted as of Oct. 20 were still far below the level needed to keep global temperatures from rising by 2 C (3.6 F), let alone 1.5 C.

To help boost national efforts and accountability, Brazil has proposed a new approach it calls a globally determined contribution. Unlike the 1997 Kyoto Protocol framework, which set fixed, country-specific emission reduction targets based on historical baselines, or the 2015 Paris Agreement’s pledge-as-you-can system, it would establish global targets aligned with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals.

So, a globally determined contribution might state, for example, that the world will triple its renewable energy production and reverse deforestation by 2030. A target like that gives countries a clearer path of action. The new format would also allow city and state actions to be counted separately, increasing incentives for them to act.

As the host of the COP30 climate talks Nov. 10-21, 2025, Brazil is uniquely positioned to champion this concept. In the absence of U.S. leadership, the proposal could offer a rare opportunity for countries to collectively strengthen commitments and reshape treaty language in a way never seen before – leaving open the possibility for progress.

Wila Mannella, a research assistant and graduate student in environmental studies at USC, contributed to this article.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Shannon Gibson, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Read more:

- Why countries struggle to quit fossil fuels, despite higher costs and 30 years of climate talks and treaties

- The World Court just ruled countries can be held liable for climate change damage – what does that mean for the US?

- Loss and damage: Who is responsible when climate change harms the world’s poorest countries?

Shannon Gibson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in Texas

Local News in Texas The Outer Banks Voice Community

The Outer Banks Voice Community The Colorado Sun

The Colorado Sun KSL NewsRadio

KSL NewsRadio Santa Maria Times Safety

Santa Maria Times Safety Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News 9&10 News

9&10 News KNAU

KNAU The Hill

The Hill