Every few decades, Americans rediscover that their republic was built on a rejection – the rejection of being ruled by a monarch. Now, in one of the largest protest movements in many years, the phrase “No kings” is everywhere: on placards, online memes, and in chants aimed at a president who seems to want to rule rather than serve.

Yet the words are hardly new. They are the first note in the American political scale, the country’s founding slogan before it even had a flag.

Long before it echoed through the colonies, the slogan “No king but Jesus” rang out in the English civil war, where it was used to declare that divine authority, not royal prerogative, should rule the conscience.

Read more: In 1776, Thomas Paine made the best case for fighting kings − and for being skeptical

When it crossed the Atlantic, colonial Americans inherited a phrase, a stance and an image that could turn theology into politics and rebellion into virtue.

As Thomas Paine put it in his 1776 pamphlet, Common Sense: “Of more worth is one honest man than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.” Republican speech was invented by rejecting monarchy.

When independence was achieved, America’s experiment rested on a paradox: it needed strong leadership but feared the aura of command. “No kings” was a self-diagnosis of a nervous republic. A way of keeping the charisma of a leader on a leash.

That allergy to grandeur shaped the early republic. In the 1790s when John Adams proposed that the president be addressed as “His Highness”, he was swiftly mocked as “His Rotundity”. The laughter mattered. It expressed the conviction that democracy could not survive reverence.

By the 1830s, this suspicion of pomp had become visual. Critics of the seventh president, Andrew Jackson, issued a famous broadside “King Andrew the First” showing him crowned and trampling the constitution. It wasn’t just partisan art – it was an act of democratic hygiene.

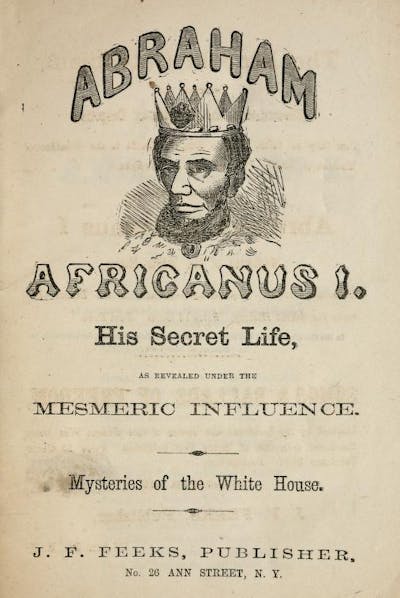

A generation later, Abraham Lincoln faced the same charge. During the American civil war, a notorious 1864 pamphlet Abraham Africanus I accused him of seeking to become a “hereditary ruler of the United States”. His sweeping wartime powers fed old fears that emergency rule would harden into monarchy.

Sometimes, the charge is justified. When Puck magazine in 1904 depicted Theodore Roosevelt crowning himself Louis XIV (or perhaps Napoleon), it captured the public’s mixture of thrill and alarm at his trust-busting, canal-building, imperial swagger. Citizens wanted vitality in office, but not vanity.

Other times, the imagery seemed to speak more to American paternal longings. Take images of Dwight Eisenhower as “King Ike” in the 1950s, a genial ruler among smiling courtiers, soothing cold war nerves.

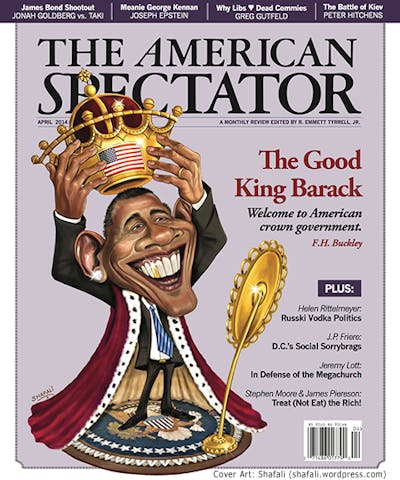

In our own century, the crown returns in sharper form. The American Spectator’s 2014 cover, “The Good King Barack” showed Obama beaming beneath a red velvet crown.

When Donald Trump triumphed in 2016, crown memes returned as America’s simplest moral shorthand for power that has gone too far.

It fell to his successor Joe Biden to officially declare, in response to the July 2024 Supreme Court ruling that Trump was not immune from prosecution: “This nation was founded on the principle that there are no kings in America.”

Why the crown keeps returning

The crown is both insult and safety valve at once. It’s an instantly legible piece of political folk art reminding citizens that authority is temporary, fallible and – like its wearer – mortal.

When protesters revive “No kings”, they aren’t just quoting the revolution. They’re translating an older language of civic republican virtue into an accent everyone can understand. No person above the law, no office above criticism, no citizen beneath respect.

The slogan reawakens the moral reflex that freedom depends on vigilance, and that dignity belongs to the governed as much as the governors.

And here’s the irony: both parties were founded on that same cry. Democrats and Republicans trace their roots to the anti-monarchical Democratic-Republicans of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who defined their movement against the spectre of kingly power. That party later fractured, giving rise to both modern traditions.

In that sense, “No kings” was the nation’s first party platform, the point of agreement from which every later disagreement grew.

Can it still work?

In today’s fractured America, “No kings” offers something rare: a language of protest that feels constitutional rather than ideological. It has the potential to speak to conservatives alarmed by executive overreach, to progressives wary of authoritarian drift, and to independents nostalgic for civic balance.

That gives it unusual rhetorical strength. Unlike most modern slogans – “Drill baby, drill”, “Make America great again” (Maga), or “Defund the police” – it doesn’t divide, it recalls a principle. “No kings” reminds Americans that what unites them is the rejection of tyranny.

The phrase also appeals to exhaustion as much as outrage. After years of political spectacle, “No kings” gestures toward humility, order and self-restraint: the virtues both parties claim to miss.

The movement may go nowhere. But if this moment does turn out to be an inflection point, it is a fitting way to frame it.

To chant “No kings” now is not nostalgia but muscle memory. That is how a republic tests its pulse: by mocking grandeur, refusing awe and rediscovering equality in the act of saying no.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Tom F. Wright, University of Sussex

Read more:

- King, pope, Jedi, Superman: Trump’s social media images exclusively target his base and try to blur political reality

- Trump is ruling like a ‘king’, following the Putin model. How can he be stopped?

- Tyrannical leader? Why comparisons between Trump and King George III miss the mark on 18th-century British monarchy

Tom F. Wright does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CNN

CNN Raw Story

Raw Story NBC News

NBC News America News

America News AlterNet

AlterNet Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top