This is the final part of our series drawing on a year of research conducted on board the Ocean Viking, the civilian search-and-rescue ship operated in the central Mediterranean by the NGO SOS Méditerranée. It explores the perspectives of exiled people based on testimonies from 110 survivors who were picked up while attempting the crossing from North Africa, as well as crew members’ experiences and the researcher’s creative collaborations on board the ship.

Catch up on parts one, two and three, and explore an immersive French-language version of the series here.

Solidarity at sea and autonomy

While my study onboard the Ocean Viking search-and-rescue ship highlighted civil rescue operations by one of the many NGOs now present in the central Mediterranean, it is important to emphasise the significance of autonomous crossings – and the many rescues and acts of solidarity at sea carried out by exiled people themselves.

For example, Ellie, a member of the SOS Méditerranée search-and-rescue (SAR) team, recounted a rescue during which two vessels in distress assisted each other:

There are people I remember very well. They had left through the Tunisian corridor in a fibreglass boat and came across another boat, wooden, which was adrift. When we arrived, we had this fibreglass boat in distress towing a wooden boat in distress, with 30 or 40 people on board. It was like a rescue of a rescue – quite incredible, this solidarity among the people at sea.

NGO crews thus seek a balance between maintaining the autonomy of exiled people, and the management of large numbers of people onboard boats in sometimes extreme conditions (often referred to as “crowd control”).

Our study on the OV precisely explored the expectations of rescued people in the immediate aftermath of rescue, known as the post-rescue phase. Their opinions made it possible to formulate several operational recommendations for the days of navigation until the rescue ship reaches a safe port in Europe.

One of the most striking findings was the need for direct communication with loved ones – particularly to inform them that the crossing had not ended fatally.

Support and information from family and friends are among the main resources available to people on the move at different stages of migration (mentioned by nearly 60% of respondents). But it is not uncommon for rescued people to lose their phone during the crossing, and even when that’s not the case, connectivity is limited in the middle of the sea.

Psychological and physical impacts

The study also revealed both the physical and psychological impacts of violence in Libya, which affect the mere ability to meet basic needs. Participants mentioned their difficulties eating, as well as finding rest and respite:

In prison we only ate once a day, we could wash only once a month.

My back is very painful, I cannot sleep.

My mind is too stressed and I can’t control it.

These traces are also visible in the countless graffiti drawings left on the Ocean Viking’s walls over the years.

In this chain of violent borders, the stay on the rescue ship represented a breathing space, judging by the open-ended comments offered at the end of our questionnaire:

We are treated like your brothers here; it’s so different from Libya!

I don’t have much to say, but I will never forget what happened here.

In the middle of the sea, when the number of people on board allowed it, we would sometimes witness moments of regained intimacy – or, conversely, collective jubilation, most notably when a port assigned by Italy as a landing point for the survivors was announced.

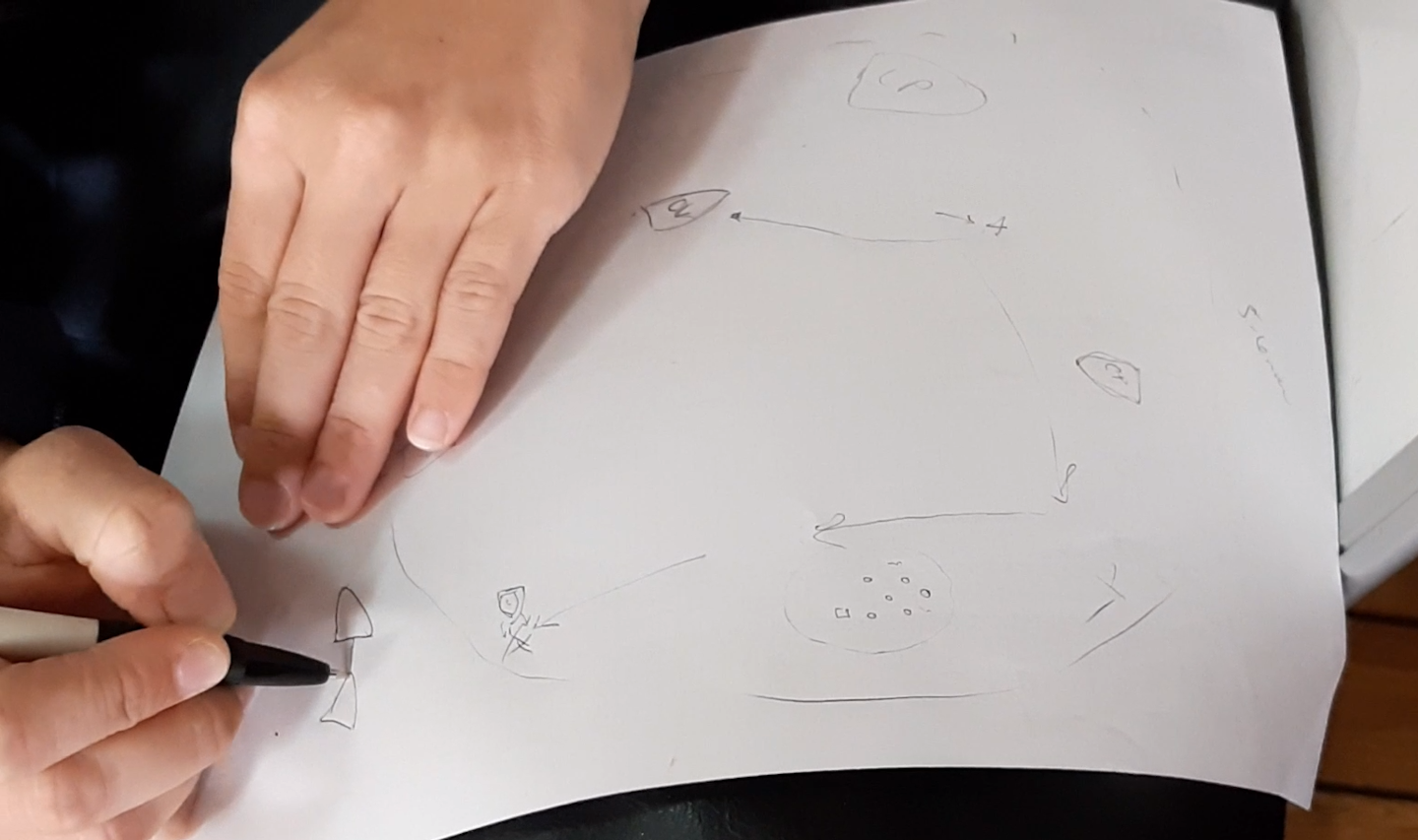

As for the mapping workshops and the questionnaire study I conducted, participant feedback suggests that they were able to engage in a form of empowerment – or at least, in the power to reflect and to narrate their experiences.

It’s the first time in a very long time that someone asked me what I think and what my opinions are about things.“

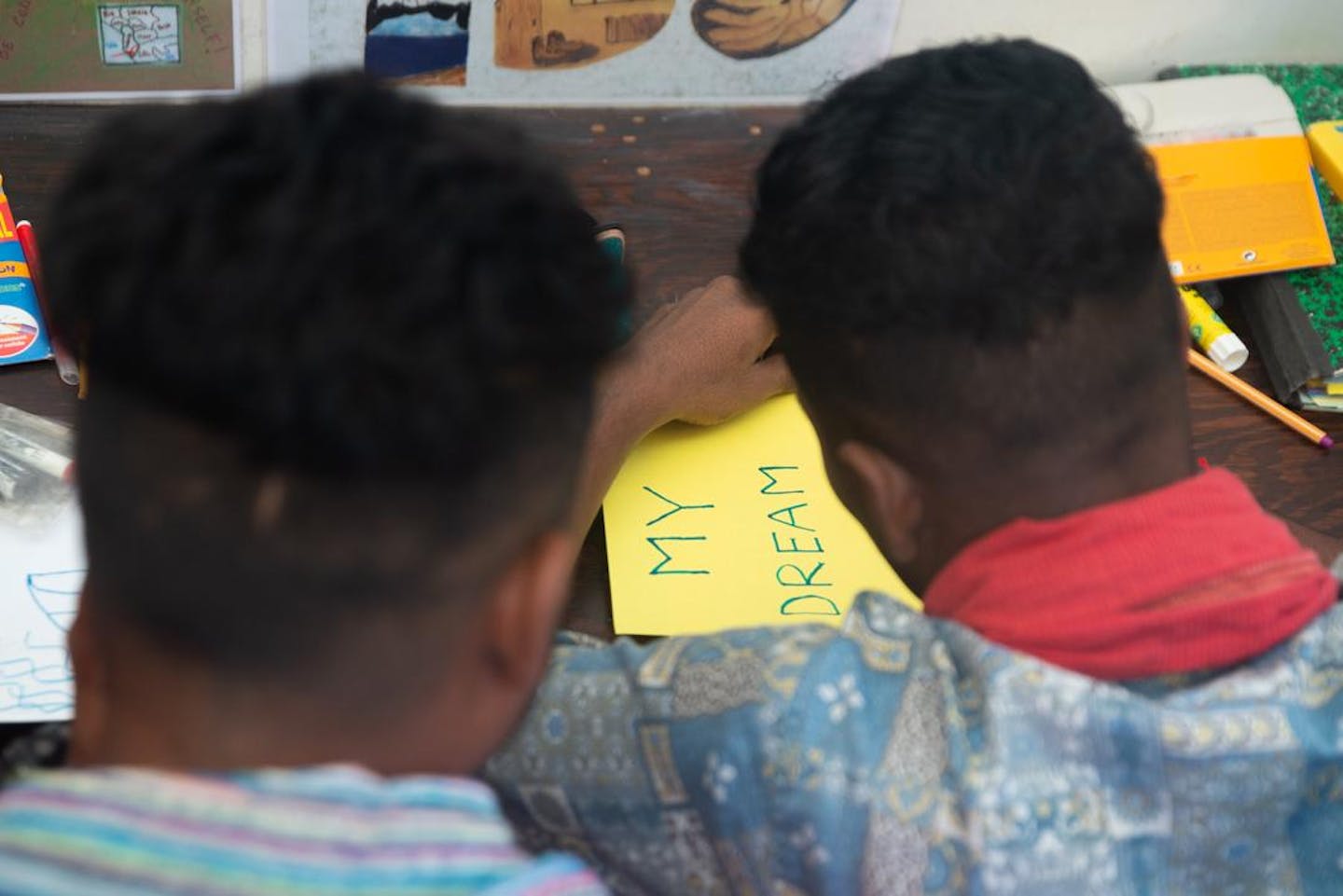

A sense of regained control over their actions emerged as the prospect of disembarkation and a new life in Europe drew near. As we sailed towards the Italian coast, the drawings and comments gathered from survivors on our collective exercises illustrated their increasingly concrete dreams and imaginings:

I hope to quickly get a residence permit in Germany.

I’m thinking to give back the money I borrowed to its owners, learn the language fast, and see my family safe and healthy.

A new form of violence

One can imagine the emotion of setting foot for the first time in a European port for those who finally make it. But what is less often imagined is that this step can represent a new form of violence. In Ancona, for example, Koné recalled the impression left by the heavy deployment of forces when they arrived:

When I got off the boat, I saw so many sirens that I thought: ‘Are there only ambulances in Italy?’

The welcome committee for people disembarking in Italy after being rescued at sea is composed of national security authorities (police and the carabinieri), Italian health services, the Italian Red Cross and Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency – whose intervention is systematically oriented around a single question: "Who was driving the boat from Libya?” In other words: “Who could be prosecuted for facilitating unauthorised entry into the territory of the European Union?”

At the level of international search-and-rescue (SAR) conventions, the rescue officially ends once people are disembarked in a “place of safety”. For the SOS Méditerranée crews, it is customary to consider that the work stops there – even if human relationships sometimes continue afterwards.

For civilian search-and-rescue NGOs, disembarkation is quickly followed by many administrative procedures and interrogations that they must undergo to avoid the risk of vessel detention, which would prevent a ship going back out into the operational area to continue its rescue missions.

After several days aboard the Ocean Viking together, the goodbyes are tinged with both joy and anxiety, as we know that for each of these individuals, a new journey of struggle is beginning.

In this fleeting moment of grace, when dreams touch the ground, I am struck by the profound power of silence.

The silence of the sea that swallowed so many bodies.

The focused silence of rescue teams when RHIBs race toward distressed boats.

The stunned silence aboard the same RHIBs bringing people back to the mothership, still dazed from escaping shipwreck.

The exhausted silence of survivors regaining their strength; the palpable silence as I listen to their stories on the deck of the Ocean Viking.

The tentative silence as the Italian coast appears for the first time.

The silence of European institutions, which conceal and obstruct the efforts to save lives at sea – and on land, by supporting interceptions and forced returns to Libya.

And finally, my own silence, faced with the awareness of my powerlessness toward the exiled people I met at sea:

I know you’re writing – it’s good, people will see it. But the story will go on.

Acknowledgements

Heartfelt thanks go to everyone who participated in this onboard study and shared their stories, especially Koné and Shakir, as well as to all the teams at sea and on land who supported my long-term research, in particular Carla Melki and Amine Boudani. I also warmly thank Rafik Arfaoui and Elizabeth Hessek for their assistance with translations from Arabic and into English.

Note: some real first names were used in these articles and others were changed , according to the preferences of the people concerned.

You can also read this entire series in French

Interactive version: En pleine mer: Un an sur l'Ocean Viking

À bord de l’« Ocean Viking » (1) : paroles de personnes exilées secourues en mer

À bord de l’« Ocean Viking » (2) : avant la mer, les périls des parcours

À bord de l’« Ocean Viking » (3) : échapper à la Libye, survivre à la mer

À bord de l’« Ocean Viking » (4) : quand les rêves touchent terre

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Morgane Dujmovic, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS)

Read more:

- ‘We were treated like animals’: the full story of Britain’s deadliest small boat disaster

- Slave auctions in Libya are the latest evidence of a reality for migrants the EU prefers to ignore

- Migrants calling us in distress from the Mediterranean returned to Libya by deadly ‘refoulement’ industry

Morgane Dujmovic does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Reuters US Domestic

Reuters US Domestic KRWG Public Media

KRWG Public Media Reuters US Politics

Reuters US Politics El Paso Times

El Paso Times NBC News

NBC News The Bay City Times

The Bay City Times The List

The List Raw Story

Raw Story