Protests erupted in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, in October 2020 following disputed parliamentary elections. Only four political parties out of 16 had passed the threshold for entry into parliament. Three of these had close ties to the country’s then-president, Sooronbay Jeenbekov.

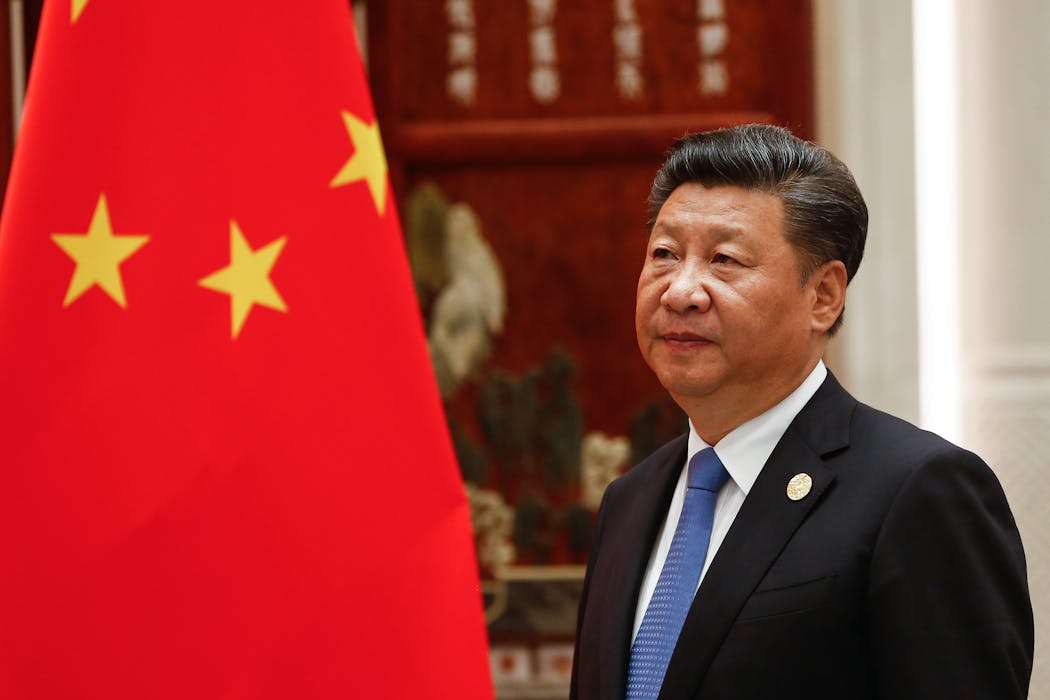

Kyrgyzstan’s powerful neighbour, China, responded to the unrest with restraint – but in a way that implied democracy can cause political upheaval. Hua Chunying, spokeswoman for the Chinese foreign ministry, said: “China sincerely hopes that all parties in Kyrgyzstan can resolve the issue according to law through dialogue and consultation, and push for stability as soon as possible”.

China adopted a different tone when Kazakhstan’s government responded violently to civil unrest in early 2022. It endorsed the Kazakh president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, repeating his claims that “terrorists trained abroad” were responsible for the unrest. Beijing praised Tokayev’s firm response, which left hundreds of people dead.

Why did China, confronted with two uprisings in neighbouring countries, react cautiously in one case and assertively in the other? As my recently published research shows, the answer points to a broader pattern in the promotion of authoritarian governance in the world today.

Researchers tend to assume that authoritarian regimes seek to export a coherent ideological model, like how the Soviet Union once promoted communism. The Soviet Union declared the aim of advancing communism abroad during the cold war, presenting one-party rule and central planning as a model for sympathetic regimes to adopt.

But few autocracies nowadays have a common ideological model to advance. Repressive regimes like the one in Beijing instead look to normalise autocratic practices elsewhere by presenting them as reasonable solutions to pressing governance challenges.

I call this “autocracy commercialisation”. Just as products are marketed differently depending on the consumer, China encourages autocratic practices in different ways that are tailored to local conditions.

Different approaches

The Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan examples illustrate this dynamic. Since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan was for many years considered the most democratic country in central Asia. It had an active political opposition, as well as a vibrant civil society and independent media outlets.

Here, Beijing has relied on what I describe in my research as a “defensive logic”. This has seen it present autocratic practices to Kyrgyzstan’s political leaders as a possible bulwark against democratic volatility. These practices have ultimately been accepted, and Kyrgyzstan has further descended towards authoritarianism.

During the unrest in 2020, Chinese officials and state media repeatedly warned that continued political turmoil could undermine Kyrgyzstan’s development. They urged all parties to resolve issues swiftly “through dialogue and consultation”. Through these claims, Beijing presented stability as the highest political good and implied that elections – and, by extension, participatory democracy – can lead to chaos.

Following the protests, the electoral authorities in Kyrgyzstan annulled the results of the elections. Jeenbekov accused “political forces” of trying to seize power illegally and subsequently resigned. He told the BBC he was ready to hand over “responsibility to strong leaders”.

A nationalist politician called Sadyr Zhaparov rapidly consolidated power in Kyrgyzstan after Jeenbekov’s resignation. He first declared himself acting president before being officially elected several months later in a vote criticised for lacking genuine competition.

China swiftly recognised his government, treating it as a return to order after a period of instability. In 2024, Kyrgyzstan then put forward new laws to give more power to governing authorities and curb dissent. Media freedoms have also narrowed under Zhaparov’s rule and civil society space has shrunk.

Kazakhstan shows a different picture – demonstrating what I call an “affirmative logic”. When protests over fuel prices escalated into nationwide unrest in January 2022, Chinese officials aligned themselves with the government’s account of events. They emphasised terrorism and foreign interference as the root causes.

China not only fully supported Tokayev and praised his leadership. It also highlighted the stabilising roles of regional security organisations such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which sent troops to Kazakhstan to help tackle the protests, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Autocracy was framed affirmatively by Beijing as the guarantor of order.

Kazakhstan has subsequently continued along its authoritarian path. In April 2024, for instance, a new media law came into effect that gave the ministry of information powers to block accreditation of foreign media and their representatives if they deem them as posing a threat to national security.

These two cases show how China adapts its narratives to different contexts. This adaptability is powerful. By promoting autocracy as a flexible and context-sensitive practice, regimes such as the one in Beijing render it legitimate and, at times, preferable to any other.

Recognising this strategy is essential for those concerned with the global clash between democracy and authoritarianism. It helps explain why autocracy persists across diverse settings and why its appeal may be broader than many people suggest.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Giulia Sciorati, London School of Economics and Political Science

Read more:

- The world’s democratic recession is giving China more power to extend authoritarianism

- Kazakhstan’s internet shutdown is the latest episode in an ominous trend: digital authoritarianism

- In Kyrgyzstan, creeping authoritarianism rubs up against proud tradition of people power

Giulia Sciorati does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top Raw Story

Raw Story Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News AlterNet

AlterNet Associated Press US and World News Video

Associated Press US and World News Video Reuters US Economy

Reuters US Economy CNN Politics

CNN Politics CNN

CNN The List

The List