Even before Donald Trump admitted on “60 Minutes” to having “no idea” who his latest pardon recipient, disgraced cryptocurrency founder Changpeng Zhao, is, the president has been upending pardon norms since his first term and even more so in his second administration, a former pardon attorney and legal experts told Raw Story.

From pardoning former Rep. George Santos early into his seven-year prison sentence for aggravated identity theft and wire fraud, to granting blanket pardons for more than 1,500 defendants involved in the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection, Trump has issued pardons since resuming office in January with unprecedented “brazenness,” experts say.

“This is a truly dramatic change from the first administration,” said Nora Demleitner, a legal scholar and former president of St. Johns College in Annapolis, Md.

Sam Morison, who served for 13 years as a staff attorney for the Office of the Pardon Attorney in the Department of Justice (DOJ), said, “President Trump has a different understanding of what makes somebody a good candidate for a pardon.”

“The traditional way it works is you have to go through DOJ, and you sort of have to kiss the ring.”

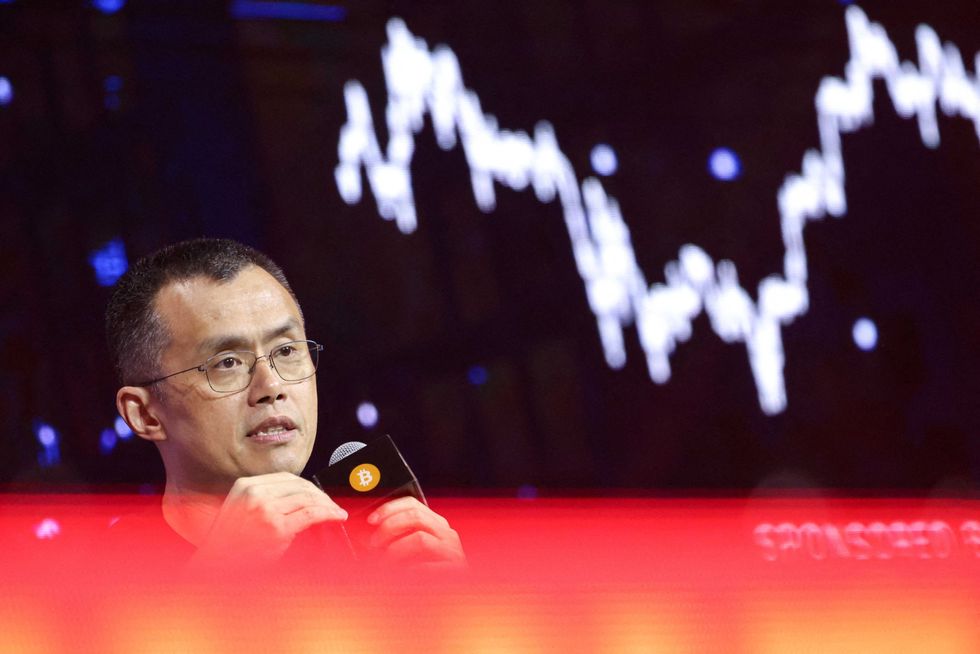

FILE PHOTO: Binance founder Changpeng Zhao, also known as CZ, speaks at the Bitcoin Asia conference, in Hong Kong, China, on Aug. 29. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu/File Photo

FILE PHOTO: Binance founder Changpeng Zhao, also known as CZ, speaks at the Bitcoin Asia conference, in Hong Kong, China, on Aug. 29. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu/File Photo

Trump made a practice of bypassing the pardon office in his first term and has continued to do so in his second term, granting pardons in cases that normally wouldn’t qualify by office standards, such as pardoning violent offenders like some Jan. 6 defendants.

Yet, the checks on the presidential pardon power are “almost none,” said Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis, allowing Trump to issue pardons despite perceptions of impropriety or political favors.

“It does seem like he tends to grant cases where at least he thinks he's getting something out of it, whether it's financial or political or whatever. He views this in a sort of transactional way. That seems to be true,” Morison said.

“I have yet to see him do one that was altruistic.”

‘Dead on arrival’

Trump’s pardoning practices are atypical in a variety of ways.

For one, Morison said the pardon office has an “informal rule” where “if somebody had a large outstanding restitution order or a large outstanding fine, that was a reason sufficient to recommend denial of the petition, and they were almost always denied.”

Trump has pardoned individuals with mutlimillion dollar restitution orders. For example, in March, Trump pardoned Trevor Milton, founder of electric vehicle company, Nikola Corporation, who was convicted of securities and wire fraud and ordered to pay $680 million in restitution to shareholders.

In another case, Trump pardoned reality TV stars Julie and Todd Chrisley for their bank fraud convictions in May, releasing them from prison and erasing any remaining obligations on the original $4.7 million and $17.2 million restitution owed, respectively, according to the Department of Justice.

“Trump has gotten comfortable with not just releasing somebody from prison, but remitting the punishment altogether, including fines and restitution, and that happened occasionally, but that was not the norm previously,” Morison said.

Traditionally, pardon applications where petitioners frame themselves as treated unfairly or as victims of a political prosecution would never be granted because “you're implicitly criticizing the Justice Department who brought the underlying case,” Morison said.

“In what I would call a normal administration, those kind of cases are almost always dead on arrival,” Morison told Raw Story .

Trump has called prosecutors in criminal cases he’s faced “scum,” “evil” and “corrupt.”

During his “60 Minutes” interview, Trump said he pardoned Zhao, who pleaded guilty to violating anti-money laundering laws at cryptocurrency exchange Binance, because his “sons are into” cryptocurrency, and he was told Zhao was “set up” by President Joe Biden’s administration.

“I heard it was a Biden witch hunt,” Trump said.

“I have no idea who he is. I was told that he was a victim, just like I was and just like many other people, of a vicious, horrible group of people in the Biden administration.”

Demleitner said Trump’s frequent allegations of political targeting by prosecutors “undermines the criminal justice system.”

Nora Demleitner (provided photo)

Nora Demleitner (provided photo)

“It's a very interesting victim mentality that's going on here,” Demleitner said.

“There's absolutely no indication that any of these were politically motivated prosecutions, just to be clear … there's no indication of that at all, and they were prosecuting Democrats and Republicans, and they were going after people who violated laws.”

Osler agreed: “It's going to put into the minds of the public that prosecutors within the Department of Justice have improper motives, and I think for the most part, the vast majority don't."

‘Dangerous’

Zhao’s pardon brought scrutiny for its appearance of “pay for play” as Binance helped facilitate a $2 billion purchase involving a Trump family-backed cryptocurrency, which Trump denied knowing anything about during his “60 Minutes” interview.

Binance’s current CEO denied boosting the Trump cryptocurrency prior to Zhao’s pardon.

But Marina Pino, who serves as counsel in the elections and government program at nonpartisan law and policy institute the Brennan Center for Justice, said “the scale and brazenness is different” with Zhao’s pardon.

“We see here that the president is looking to give out pardons to those that can enrich himself, or those who have shown very clearly through donations, either through his campaign or his inaugural fund, that they can receive special treatment, and that itself is dangerous,” Pino said.

“We should all be very concerned."

Pardons can be “bought or flattered” under today's Trump administration, Demleitner said.

For instance, Milton and his wife donated more than $1.8 million to a Trump re-election fund less than a month before the 2024 election.

“I think some of it is fulfilling campaign promises, and I assume it has to do with [Trump] feeling abused and prosecuted, and so he'll align with everybody who he either believes was abused, prosecuted in an inappropriate manner, or who tells them that they were prosecuted inappropriately,” Demleitner said.

FILE PHOTO: George Santos, who was expelled from the U.S. House of Representatives, departs after the sentencing in his criminal corruption charges at Central Islip Federal Courthouse in Central Islip, New York on April 25, 2025. REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton/File Photo

FILE PHOTO: George Santos, who was expelled from the U.S. House of Representatives, departs after the sentencing in his criminal corruption charges at Central Islip Federal Courthouse in Central Islip, New York on April 25, 2025. REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton/File Photo

In Santos’ case, more than $373,000 in restitution was erased, along with the remainder of his 87-month prison sentence through Trump’s Oct. 17 pardon.

Santos was less than three months into his sentence, which is an atypically quick timeline since “usually you're getting a pardon years after a conviction, so you can show you have rehabilitated,” Demleitner said.

“It's rewarding public loyalty because Santos had very publicly and flagrantly said, ‘I think Donald Trump is great,’ so he's reinforcing the point that you're either for me or you're against me,” Morison said.

‘Doom loop’

Liz Oyer, a former Department of Justice pardon attorney fired by Trump, calculated the cost of Trump’s second term pardons to be more than $1 billion as of May.

A June memo from the Democratic staff of the House Committee on the Judiciary calculated a $1.3 billion cost for pardons.

Determining an exact financial impact of the pardons is challenging because oftentimes fines and restitution go uncollected, Morison said. Theoretically, taxpayers could save some money when someone is released from prison considering it costs the Bureau of Prisons at least $30,000 per year to keep someone incarcerated, he said.

But, the erasure of restitution can have a significant impact on individual victims , Osler said.

While victims can still pursue damages via a civil suit, that puts more of a “burden on victims ... because the government's not going to be doing anything to collect it if the person has been pardoned," Morison said.

“The fact that they're not being made whole certainly matters,” Osler said. “It’s a big loss for a lot of those people, and even when it's an institution that is the victim, some of these amounts are so large that you have to believe they have an impact.”

Pino said the moment is right to push for “structural reforms” to fight against “pay to play culture,” recommending more transparency in the pardon power process, at a minimum.

“If folks are angry about the pardon President Biden gave to Hunter, and then they're angry about this pardon to Zhao, the answer is to get behind actual reforms to bring more accountability to this process,” Pino said.

“Otherwise, we're stuck in this doom loop where one side is angry at the other and nothing changes.”

Raw Story

Raw Story

Esquire

Esquire RadarOnline

RadarOnline