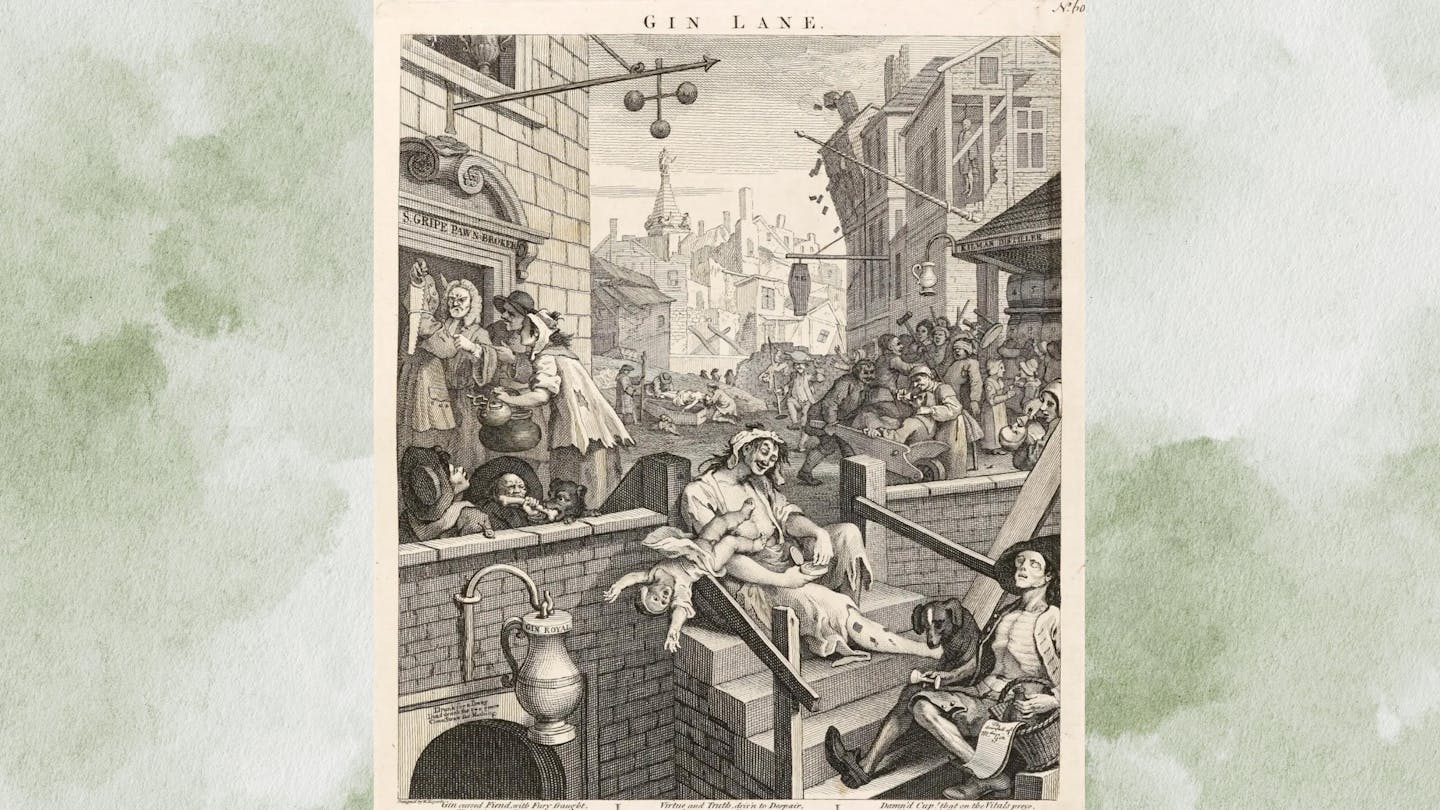

In 1751, the English painter William Hogarth created a nightmarish depiction of the London slum of St Giles. The familiar spire of the parish church towered over a scene of human ruin. This is Gin Lane, an imagined thoroughfare where the consumption of gin has deprived the inhabitants of sense, finances – and in some instances life.

At the heart of the image, Hogarth depicted a series of steps on which different characters illustrated the gin drinker’s descent from propriety to death. At the top of the steps, residents deposited their goods with the prosperous pawnbroker, including a carpenter who handed over his saw – a reminder that gin disrupts industry.

Just below on the steps is a drunken mother whose eagerness to take a pinch of snuff causes her baby to slip from her arms to its death below. The drunken mother is the most striking aspect of Hogarth’s image, a focal point that represents how gin detaches the drinker from their closest bonds and duties. Beneath the mother, reclines an emaciated gin drinker whose skeletal features hint at his imminent death. He even lacks the strength to hold his gin glass.

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books, films and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

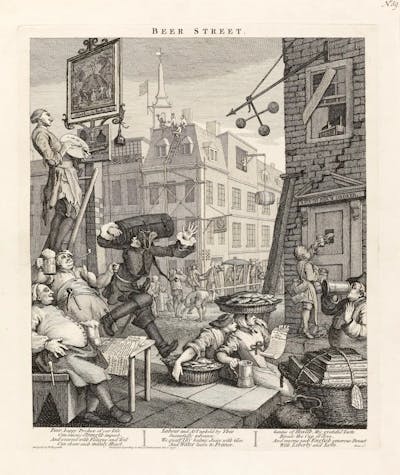

Gin Lane was one of two contrasting Hogarth visions of life in England’s capital in which the fortunes of Londoners were shaped by the drinks they consumed. The inhabitants of the other, Beer Street (1751), are artisans enjoying a foaming tankard during their long day of work.

A blacksmith and paviour (person who lays paving) are in the foreground, while a man tasked with carrying a sedan chair quenches his thirst in the background.

Beer Street is a scene of industriousness in which draughts were consumed without disrupting the effort of the day. High in the scene, a group of workers enjoys beer shared from a jug while a tailor toasts them from a nearby window. The inhabitants’ prosperity has just one noticeable consequence in the tattered premises of the pawnbroker.

While Gin Lane can be read as a commentary on the dangers of vice, I believe it also comments on another significant development in 18th-century London – the growth of the funeral trade.

Birth of the undertaker

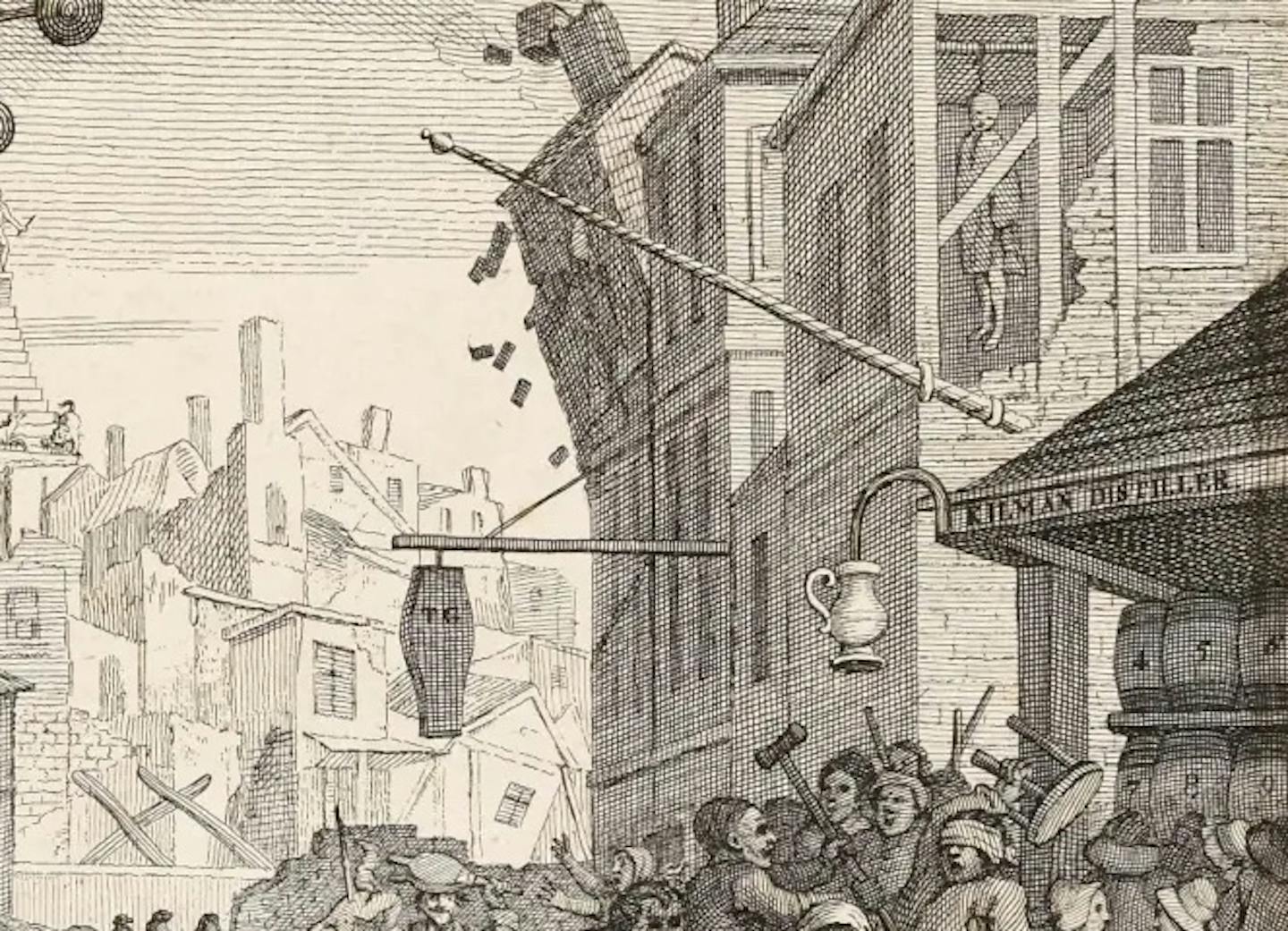

Just above the shoulder of the drunken mother are two coffins. One lies on the ground as a body is placed in it and the other is suspended outside the premises of an undertaker. This latter coffin was a shop sign, which could be seen across the city in the mid- to late-18th century. Undertaking was a developing trade that had many advocates. These undertakers were artisans or traders who supplemented their existing businesses with funerary work.

Undertakers were primarily middlemen who sourced the items required for a funeral, as well as providing items from their own stock. A carpenter acting as undertaker, for example, might build a coffin himself, before turning to ironmongers, drapers and painters for other elements of funerary display.

The supplemental nature of early undertaking enabled many people to adopt the title and some of the most successful eventually specialised fully in funerary work. In the closing decades of the 17th century, the earliest undertakers organised the elaborate funerals of elites, having previously supplied goods for these occasions. As the trade spread, its development was driven by profit and therefore thrived in urban centres where there were more prospective customers.

The presence of the undertaker’s shop in Hogarth’s Gin Lane is a reflection of the trade’s increasing popularity beyond the early origins in funerals of the elite.

By the mid-18th century, undertaker-led funerals were a common sight on the city’s streets, travelling from bereaved households to parish churches. The upstart trade had drawn criticism as early as 1699 when the author Thomas Tryon argued that undertakers were diminishing the worth of the funerary customs of the elites. And for many critics, there was no group thought less deserving of funerary spectacle than the gin-drinking poor.

Critiquing the undertaker

Hogarth’s inclusion of the undertaker was also a comment on the motives of the developing trade and the worth of its service. In Gin Lane, he emphasised the way that undertakers profited from the misfortune and misery of others.

He places the undertaker’s shop at the heart of a ruined street, where other trades have failed and the residents lie incapacitated and dying. His message is clear – the undertaker gains from the loss of others and so is little different from the other thriving businesses of the fictional street, the pawnbroker and the gin shop.

The opened coffin and distant funeral party can also be read as a comment on the worth of the funerary products that underpinned the trade’s success. The lidless coffin is presented as little more than a box to contain the half-naked remains of the woman who is lowered into it. And the depiction of the dead woman reminds us that the coffin does nothing for its inhabitant – its purpose is purely aesthetic.

A uniform aesthetic is important to the funerary party, wearing hatbands and mourning cloaks as they wander through the tattered background. Yet the neatly attired procession is lost within the image and fails to hold the attention of the neighbourhood. The cost of these items cannot influence the attitudes of those outside of the funeral. Through these small details, Hogarth reminds the viewer that funerary goods are a hollow expenditure, which cannot improve the circumstances of the dead or the bereaved.

Much as the inhabitants of Gin Lane ruin themselves in pursuit of gin, so might the viewer waste their money on funerary goods that do not serve any practical purpose. As such, Hogarth’s work is more than a simple comment on the consequences of the gin craze – it’s a wider critique of how 18th-century Londoners spent their money.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Dan O'Brien’s suggestion:

Juan Manuel Echavarría has used photography to document how people experience death in a time of crisis and brutality. His work Réquiem NN (2006-13) uses imagery of graves in a Colombian cemetery to explore how people’s treatment of the dead is both an act of dignity and a form of resistance.

Réquiem NN depicts graves used for unidentified bodies that have been recovered from Colombia’s Magdalena River as a result of civil war. We see each grave in two periods, bringing to life the act of mourning, which has been performed for the unnamed dead, and revealing how the living use the graves to record the names of victims who were their own relatives.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Dan O'Brien, University of Bath

Read more:

- How I found potential lost works of the great British painter William Hogarth – new research

- Nine weird and wonderful facts about death and funeral practices

- What archaeology can tell us about the lives of children in England 1,500 years ago

Dan O'Brien does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Business of Home

Business of Home Timeout New York

Timeout New York Colorado Springs Gazette

Colorado Springs Gazette WVTM 13 Entertainment

WVTM 13 Entertainment Mediaite

Mediaite Cache Valley Daily

Cache Valley Daily Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top IMDb TV

IMDb TV Crooks and Liars

Crooks and Liars AlterNet

AlterNet