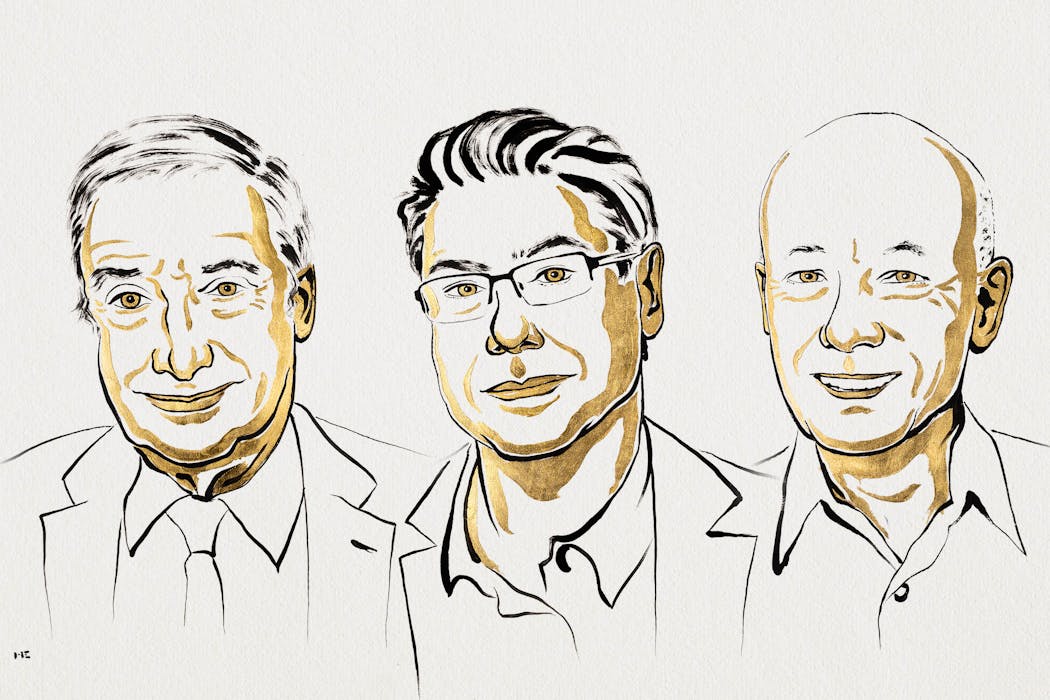

Three economists working in the area of “innovation-driven economic growth” have won this year’s Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Half of the 11 million Swedish kronor (about A$1.8 million) prize was awarded to Joel Mokyr, a Dutch-born economic historian at Northwestern University.

The other half was jointly awarded to Philippe Aghion, a French economist at Collège de France and INSEAD, and Peter Howitt, a Canadian economist at Brown University.

Collectively, the trio’s work has examined the importance of innovation in driving sustainable economic growth. It has also highlighted that in dynamic economies, old firms die as new firms are being born.

Innovation drives sustainable growth

As noted by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, economic growth has lifted billions of people out of poverty over the past two centuries. While we take this as normal, it is actually very unusual in the broad sweep of history.

The period since around 1800 is the first in human history when there has been sustained economic growth. This warns us we should not be complacent. Poor policy could see economies stagnate again.

One of the Nobel judges gave the example that in Sweden and the United Kingdom there was little improvement in living standards in the four centuries between 1300 and 1700.

Mokyr’s work showed that prior to the Industrial Revolution, innovations were more a matter of trial and error than being based on scientific understanding. He has argued that sustained economic growth would not emerge in:

a world of engineering without mechanics, iron-making without metallurgy, farming without soil science, mining without geology, water-power without hydraulics, dyemaking without organic chemistry, and medical practice without microbiology and immunology.

Mokyr gives the example of sterilising surgical instruments. This had been advocated in the 1840s or earlier. But surgeons were offended by the suggestion they might be transmitting diseases. It was only after the work of Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister in the 1860s that the role of germs was understood and sterilisation became common.

Mokyr emphasised the importance of society being open to new ideas. As the Nobel committee put it:

practitioners, ready to engage with science, along with a societal climate embracing change, were, according to Mokyr, key reasons why the Industrial Revolution started in Britain.

Winners and losers

This year’s other two laureates, Aghion and Howitt, recognised that innovations create both winning and losing firms. In the US, about 10% of firms enter and 10% leave the market each year. Promoting economic growth requires an understanding of both processes.

Their 1992 article built on earlier work on the concept of “endogenous growth” – the idea that economic growth is generated by factors inside an economic system, not the result of forces that impinge from outside. This earned a Nobel prize for Paul Romer in 2018.

It also drew on earlier work on “creative destruction” by Joseph Schumpeter.

The model created by Aghion and Howitt implies governments need to be careful how they design subsidies to encourage innovation.

If companies think that any innovation they invest in is just going to be overtaken (meaning they would lose their advantage), they won’t invest as much in innovation.

Their work also supports the idea governments have a role in supporting and retraining those workers who lose their jobs in firms that are displaced by more innovative competitors.

This will build political support for policies that encourage economic growth, as well.

‘Dark clouds’ on the horizon?

The three laureates all favour economic growth, in contrast to growing concerns about the impact of endless growth on the planet.

In an interview after the announcement, however, Aghion called for carbon pricing to make economic growth consistent with reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

He also warned about the gathering “dark clouds” of tariffs; that creating barriers to trade could reduce economic growth.

And he said we need to ensure today’s innovators do not stifle future innovators through anti-competitive practices.

The newest Nobel prize

The economics prize was not one of the five originally nominated in Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel’s will in 1895. It is formally called the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. It was first awarded in 1969.

The awards to Mokyr and Howitt continue the pattern of the economics prize being dominated by researchers working at US universities.

It also continues the pattern of over-representation of men. Only three of the 99 economics laureates have been women.

Arguably, economics professor Rachel Griffith, rather than Mokyr, could have shared the prize with Aghion and Howitt this year. She co-authored the book Competition and Growth with Aghion, and co-wrote an article on competition with both of them.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: John Hawkins, University of Canberra

Read more:

- Reform of NZ’s protected lands is overdue – but the public should decide about economic activities

- ‘Doughnut economics’ shows how global growth is out of balance - and how we can fix it

- A pro-democracy Venezuelan politician wins this year’s Nobel Peace Prize. Is it a rebuke to Trump?

John Hawkins does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

KLCC

KLCC Aljazeera US & Canada

Aljazeera US & Canada NBC Southern California

NBC Southern California Reuters US Business

Reuters US Business Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top US Magazine

US Magazine Raw Story

Raw Story