When I first studied art history in the late 1960s, all artists were men. It seemed, back then, that the act of rendering an image in line and colour, or visualising pure emotion, was confined to the gender that controlled society at the time.

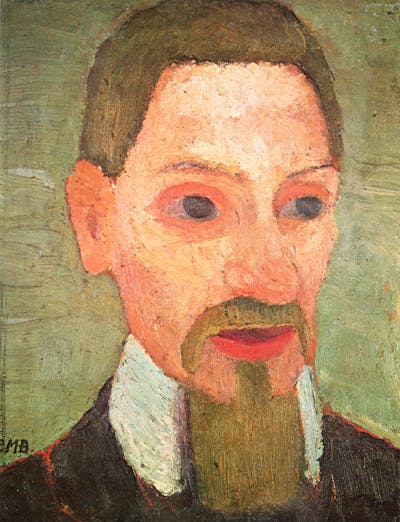

The one woman artist I remember from my undergraduate years was Paula Modersohn-Becker, whose portrait of Rilke was reproduced in Waldemar George’s Expressionism, translated from French. He wrote that her “naïve vision concealed a skilful technique”. But she died young and none of the men who wrote in English noticed her.

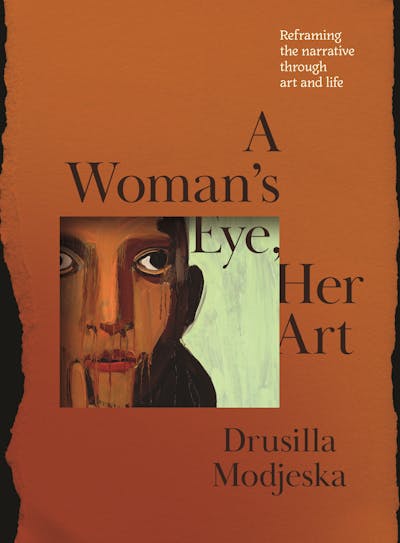

Modersohn-Becker’s determination to become an artist is one of the starting points for Drusilla Modjeska’s A Woman’s Eye, Her Art, her study of avant garde women artists in the first part of the 20th century. Their art was (sometimes) noticed when it was first made, but later they were mainly regarded as being muses for famous men.

The other starting point is the author’s ongoing conversation with living Australian artist, Julie Rrap, whose body of work has been influenced by Modersohn-Becker – as well as other women artists whose lives Modjeska discusses.

Review: A Woman’s Eye, Her Art – Drusilla Modjeska (Penguin)

In 1906 Modersohn-Becker painted a remarkable self-portrait, depicting herself as pregnant, contemplating possible futures. She was not pregnant at the time. A year later, shortly after giving birth to a much-wanted daughter, she died. Because she died in the early 20th century, at a time and in a culture when new ideas were possible, her art was preserved. Since 1927, it has been on view for all to see at the Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum.

After her death, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke honoured her memory in Requiem for a Friend. Modjeska took the title of her earlier book, Stravinsky’s Lunch, from the way composer Igor Stravinsky compelled his family to eat in silence so they would not distract his thoughts.

Stravinsky was more committed to family life than Rilke.

Clara Westhoff, a friend of Modersohn-Becker since their early student days, was a talented sculptor. It was then, in Worpswede, Germany, that she met Rilke. Their relationship flourished when she moved to Paris to study at L'Academie Julian. She was later accepted as a pupil to Rodin.

After their marriage, the couple settled in Worpswede, but shortly after their daughter was born, Rilke returned to Paris. Six weeks later, Clara joined him, leaving the baby behind on his instructions. Rilke wished Clara to be with him, but to give him privacy – and on no account was he to be bothered by the child he fathered. As Modjeska writes, he saw her as “the failed wife of an artist and therefore – by the illogic of his logic – a failure also as an artist”.

There is an echo of the Rilke/Westhoff marriage in the relationship between Russian painter Vassily Kandinsky and his former student Gabriele Münter. They did not marry, as Kandinsky was already married, but she did support him financially.

When they became part of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) artists’ collective, she – with Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke, Maria Franck and Natalia Goncharova – worked on the manifesto that defined their radical movement, Der Blaue Reiter Almanac. But when it was published, only the men were named as editors and only two of the women, Münter and Goncharova, were noted as artists.

‘Great Artist’ behaviour

As Modjeska takes the reader through the early 20th century, looping forwards and backwards to show repeated patterns of Great Artist behaviour, she comes to a natural punctuation point – World War I. The world was reconfigured, and art recognised the madness of it all with dada and surrealism.

Thanks to art historian Whitney Chadwick’s groundbreaking research on women artists, a great deal is now known of the art, including performance, by women artists in the frenetic years following the war.

Modjeska writes: “Eros was the word.” She introduces the reader to French artist Claude Cahun (born Lucy Schwob) and her partner Suzette (performing as Marcel Moore), who together staged performances, created photographs as different personas – sometimes with double exposures, and wrote. As tricksters and shapeshifters, they found their home in Paris among the growing queer community, which embraced the surrealist aesthetic.

In 1938, shortly before Germany invaded Poland, Cahun and Suzette retreated to the British Channel island of Jersey. There, they easily blended in as middle-aged French ladies of little interest to the authorities. After the German occupation of Jersey in 1940, they created the persona of a disaffected German soldier who wrote anonymous messages to his fellows about the “war without end” they were enduring, predicting defeat.

Other messages told the soldiers their officers were planning to flee to safety, leaving their men to be killed by the Allies. They were so successful in concealing their identities as they undermined the morale of the occupiers, it took years before they were discovered and arrested, in 1944.

Modjeska notes that when the evidence was laid out at their trial, the collection of “collages, leaflets, drawings, cigarette boxes, books and notebooks” could almost have been a surrealist exhibition. They were sentenced to death, but saved by the Allied invasion.

Their archive is in Jersey, where they were first honoured as war heroes. This is just as well: none of the men who avidly collected the work of the surrealists in Paris had bothered with them.

Women artists valued as ‘muses’

Although Modjeska writes in great detail of these once forgotten, now recovered, artists, she almost skims over the reasons they were lost for so long. Art becomes known to history by being seen and discussed.

André Breton, author of the Surrealist Manifesto, saw women as mysterious objects: without creativity or intellect, but able to inspire men’s creative urges. His assessment was shared by many of his fellow artists. Picasso, Man Ray and Max Ernst were all happy to exploit and discard the women in their lives.

In 1982, when Whitney Chadwick was researching her groundbreaking Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, she interviewed Roland Penrose, who as a young artist had been active in surrealist circles. After the war, he became one of the co-founders of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. As such, he was one of the most influential figures in shaping British understanding of contemporary art in the mid to late 20th century.

When she asked him about the importance of women to surrealism, Penrose replied, “of course the women were important. But it was because they were our muses.” His wife, photographer Lee Miller, had died some years before. Her complete photographic archive was stored in the attic, two floors above where Chadwick was sitting.

In 1985, the year after Penrose’s death, Thames & Hudson published The Lives of Lee Miller, written by their son Antony Penrose. The book describes how a beautiful girl from Poughkeepsie became first a model in New York, then a photographer in her own right. In Paris, she became a muse to Man Ray, before becoming one of the most original and daring photographers of the surrealist movement.

I can understand why Modjeska gives so much space to Miller. In her earlier career, she is either the author or subject of some of the most memorable of all surrealist photographs.

Her life was as colourful as her work. She had a talent for friendship. Her photographs of the surrealist artists at play show how closely the lives of the women artists were integrated with those of the men. Leonora Carrington (creator of fantastic mythical beasts), Eileen Agar (who used discarded objects to make her assemblages and collages) and especially Dora Maar (maker of absurdist photomontages), are all there.

Later, Miller photographed (for Vogue) some of the most memorable images of the final years of World War II, when she became the first photographer to enter Buchenwald Concentration camp. Her photographs manage the almost impossible task of honouring the survivors and the dead, while damning the perpetrators. Recently, that stage of her life has been celebrated in the film Lee, produced by and starring Kate Winslet.

The account of Miller’s post-war career is brief. Peacetime saw her turned into a wife. Her husband was proud of her prowess as a cook and hostess, though her son later wrote that at times she turned her culinary expertise against unpleasant house guests, as a weapon.

On one occasion, after English critic Cyril Connolly claimed Americans had “the moral strength of a marshmallow and will drown themselves in a sea of that revolting beverage, Coca-Cola”, Miller retired to the kitchen. That night, she served delicious dessert. When Connolly praised it, she told him the ingredients: marshmallow and Coca-Cola.

Modjeska suggests Miller’s often erratic behaviour meant she suffered from PTSD, but it is clear she was experiencing more than that.

Rethinking the impossible

In three paragraphs on page 427, Modjeska writes of the circumstances that proscribed not only the lives of Miller and her colleagues, but also women in many other occupations.

As order was restored after years of chaos, the men in charge sent the women home. The responsible jobs they had held during the war were given to men who were no longer soldiers. The women were told in no uncertain terms that their new mission was to be homemakers, their sphere now limited to the domestic.

This was the context that saw women artists disappear from art’s histories for many years – a fate they shared with women bus drivers, factory workers and office managers. It is hardly surprising so many of these women experienced the kind of depression described so well in Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique.

An epilogue describes Julie Rrap’s SOMOS – Standing on My Own Shoulders, exhibited at Sydney’s MCA. In standing up for herself, Rrap also acknowledges the influence of many artists of the past.

Although this book is the result of many years of research, it was completed in the uncertainty of 2025. Modjeska writes: “as our world becomes more precarious, we too need the strength to rethink the impossible, and maintain hope in the possible”.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Joanna Mendelssohn, The University of Melbourne

Read more:

- Lee Miller retrospective confirms her as one of the most important photographers of the 20th century

- Theft, lies and butterflies: the Englishman who stole thousands of specimens from our museums

- How the high-rise tower block came to symbolise the contradictions of modern Britain

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the ARC

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Emporia Gazette

The Emporia Gazette The Spectator

The Spectator The Hollywood Reporter

The Hollywood Reporter NPR

NPR KUOW Public Radio

KUOW Public Radio Ideastream

Ideastream Nicki Swift

Nicki Swift Daily Kos

Daily Kos Vanity Fair

Vanity Fair OK Magazine

OK Magazine