Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) rose faster in 2024 than in any year since records began – far faster than scientists expected.

Our new satellite analysis shows that the Amazon rainforest, which has long been a huge absorber of carbon, is struggling to keep up. And worryingly, the satellite that made this discovery could soon be switched off.

Systematic measurements of CO₂ in the atmosphere began in the late 1950s, when the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii (chosen for its remoteness and untainted air) registered about 315 parts per million (ppm). Today, it’s more than 420ppm.

But just as important is the rate of change. The annual rise in global CO₂ has gone from below 1ppm in the 1960s to more than 2ppm a year in the 2010s. Every extra ppm represents about 2 billion tonnes of carbon – roughly four times the combined mass of every human alive today.

Across six decades of measurements, atmospheric CO₂ has gradually increased. There have been some large but temporary departures, typically associated with unusual weather caused by an El Niño in the Pacific. But the long-term trend is clear.

In 2023, CO₂ in the atmosphere grew by about 2.70ppm. That’s a large step up, but not too unusual. Yet in 2024, it was an unprecedented 3.73ppm.

How satellites observe atmospheric CO₂

Until recently, we could only monitor CO₂ through stations on the ground like the one in Hawaii. That changed with satellites such as Nasa’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO-2), launched in 2014.

The OCO-2 satellite analyses sunlight reflected from Earth. Carbon dioxide acts like a filter, absorbing specific wavelengths of light. By observing how much of that specific light is missing or dimmed when it reaches the satellite, scientists can accurately calculate how much CO₂ is in the atmosphere.

But air is always on the move. The CO₂ above any one point can come from many sources – local emissions, nearby forests, or air carried from far away. To untangle this mix, scientists use computer models that simulate how winds move CO₂ around the globe.

They then adjust these models until they match what the satellite sees. This gives us the most accurate estimate possible of where carbon is being released and where it’s being absorbed.

The decade-long data record from OCO-2 allows us to put 2023 and 2024 into historical context.

The result

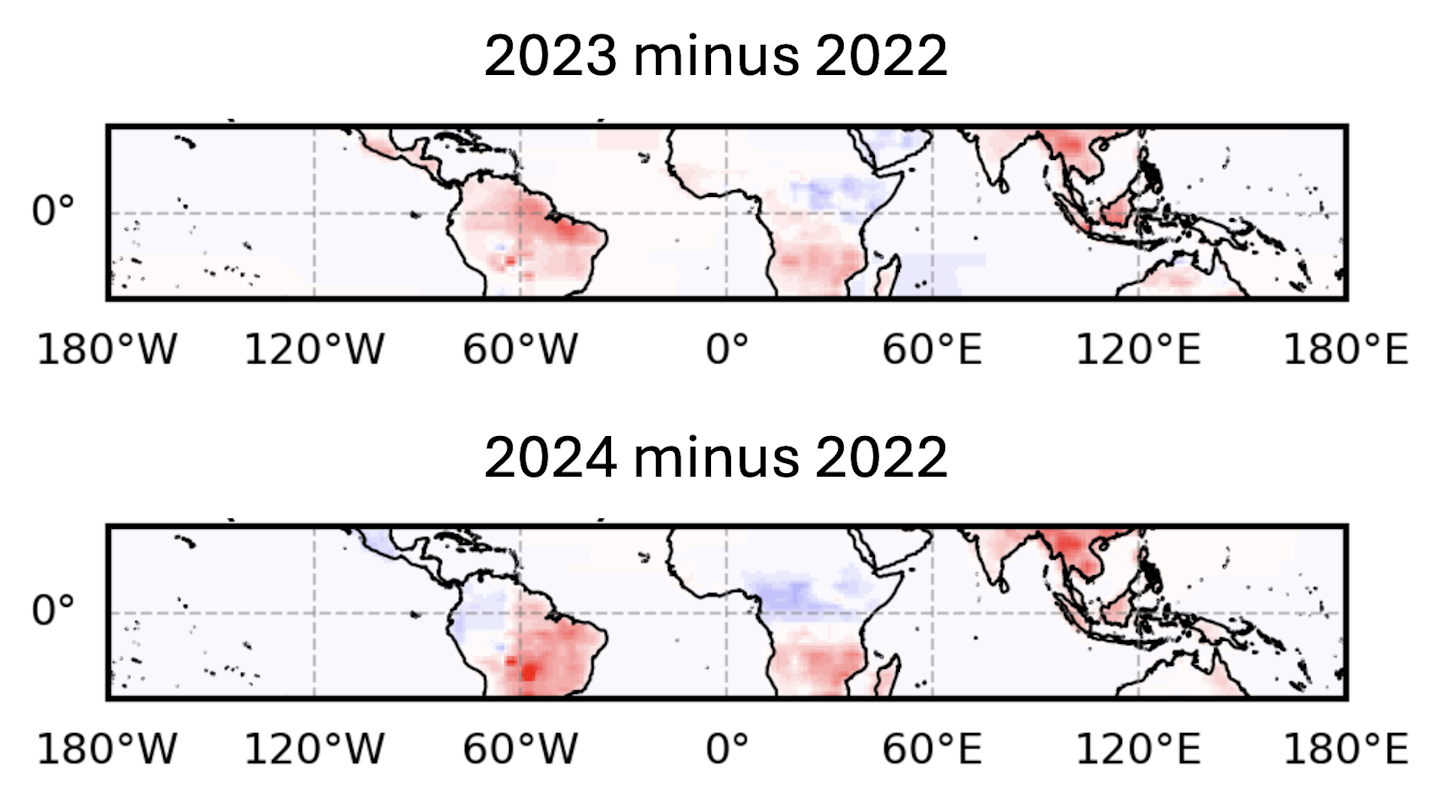

From the satellite data, we infer that the largest changes in CO₂ emissions and absorption during 2023 and 2024, compared with the baseline year of 2022, were over tropical land.

The largest change was over the Amazon, where much less CO₂ is being absorbed. Similar slowdowns also appeared over southern Africa and southeast Asia, parts of Australia, the eastern US, Alaska and western Russia.

Conversely, we detected more carbon being absorbed over western Europe, the US and central Canada.

Other data backs this up. For instance, plants emit a faint glow as they photosynthesise – remarkably, we can see this glow from space. Measurements of this glow along with vegetation greenness both show that tropical ecosystems were less active in 2023 and 2024.

Our analysis suggests that warmer temperatures explain most of the Amazon’s reduced capability to absorb carbon. Elsewhere in the tropics, changes in rainfall and soil moisture were more important.

Why 2023 and 2024 were special

In many ways, these years resembled previous El Niño years such as 2015-16, when drought and heat led to less carbon absorption and more wildfires. But what’s interesting about 2023-24 is that the responsible El Niño event was comparatively weak.

Something else must be amplifying the effect. The most likely culprit is the extensive, record-breaking drought that has gripped much of the Amazon basin. When plants are already stressed by a lack of water, even modest warming can push them beyond their tolerance, reducing their ability to absorb carbon.

Roughly half of the CO₂ emitted by humans stays in the atmosphere. The other half is absorbed, more or less equally, by the land and the oceans. If drought or heat means plants are less able to absorb carbon, even temporarily, more of our emissions will remain in the air.

Our ability to meet climate targets relies on nature continuing to provide this vital carbon storage.

Satellite shutdown

It’s not yet clear whether 2023-24 is a short-term blip or an early sign of a long-term shift. But evidence points to an increasingly fragile situation, as tropical forests are stressed by hot and dry conditions.

Understanding exactly how and where these ecosystems are changing is essential if we want to know their future role in the climate, and whether drought will delay their recovery. One step is to urgently send scientists to tropical ecosystems to document recent changes in person.

That’s also where satellites like OCO-2 come in. They offer global and almost real-time coverage of how carbon dioxide is moving between the land, oceans and atmosphere, helping us separate temporary effects like El Niño from deeper changes.

Yet, despite being fit and healthy and having enough fuel to keep it going until 2040, OCO-2 is at risk of being shut down due to proposed Nasa budget cuts.

We wouldn’t be blind without it – but we’d be seeing far less clearly. Losing OCO-2 would mean losing our best tool for monitoring changes in the carbon cycle, and we will all be scientifically poorer for it.

The Amazon is sending us a warning. We must keep watching – while we still can.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Paul Palmer, University of Edinburgh and Liang Feng, University of Edinburgh

Read more:

- India’s monsoon is becoming more extreme – even though overall rainfall has hardly increased

- We pumped extra CO₂ into an oak forest and discovered trees will be ‘woodier’ in future

- How satellites revolutionised climate change science

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in Texas

Local News in Texas The Outer Banks Voice Community

The Outer Banks Voice Community The Colorado Sun

The Colorado Sun KSL NewsRadio

KSL NewsRadio Santa Maria Times Safety

Santa Maria Times Safety Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News 9&10 News

9&10 News KNAU

KNAU Atlanta Black Star Entertainment

Atlanta Black Star Entertainment