This is the third part of our series drawing on a year of research conducted on board the Ocean Viking, the civilian search-and-rescue ship operated in the central Mediterranean by the NGO SOS Méditerranée. It explores the perspectives of exiled people based on testimonies from 110 survivors who were picked up while attempting the crossing from North Africa, as well as crew members’ experiences and the researcher’s creative collaborations on board the ship.

Catch up on parts one and two, or explore an immersive French-language version of the series here.

‘The worst decision of my life’

The dangers of Libya are generally discovered only when people on the move enter that country with hopes of finding decent work and a better life. One survivor told me while they were on board the Ocean Viking (OV): “On my very first day in Tripoli, I realised I had made the worst decision of my life.”

Few people manage to transit through Libya in less than a month. As Koné explained when we met in Ancona, on the Adriatic coast of Italy: “In Libya, it’s not easy to get in, but it’s even harder to get out!”

Most of those we met on the OV (57.9%) had spent between one and six months in Libya. But some had been trapped there for over two years – and for one Sudanese participant, up to seven years in total.

Different migration routes and configurations emerged from the survey, with the longest forced stays in Libya mainly affecting people from the poorest and most war-torn countries.

Another significant finding was that women experienced longer periods of detention in Libya – those we met had spent an average of 15½ months there, compared with 8½ months for men. This reflects the mechanisms of coercion and violence that specifically affect women migrating through the Mediterranean, as was powerfully described by Camille Schmoll in her 2024 book, The Wretched of the Sea.

Mohamad’s experience of Libya

Under the conditions in Libya described to us, the decision to take to the sea despite the risks of a Mediterranean crossing could be summed up like this: better the risk of dying now than the certainty of a slow death.

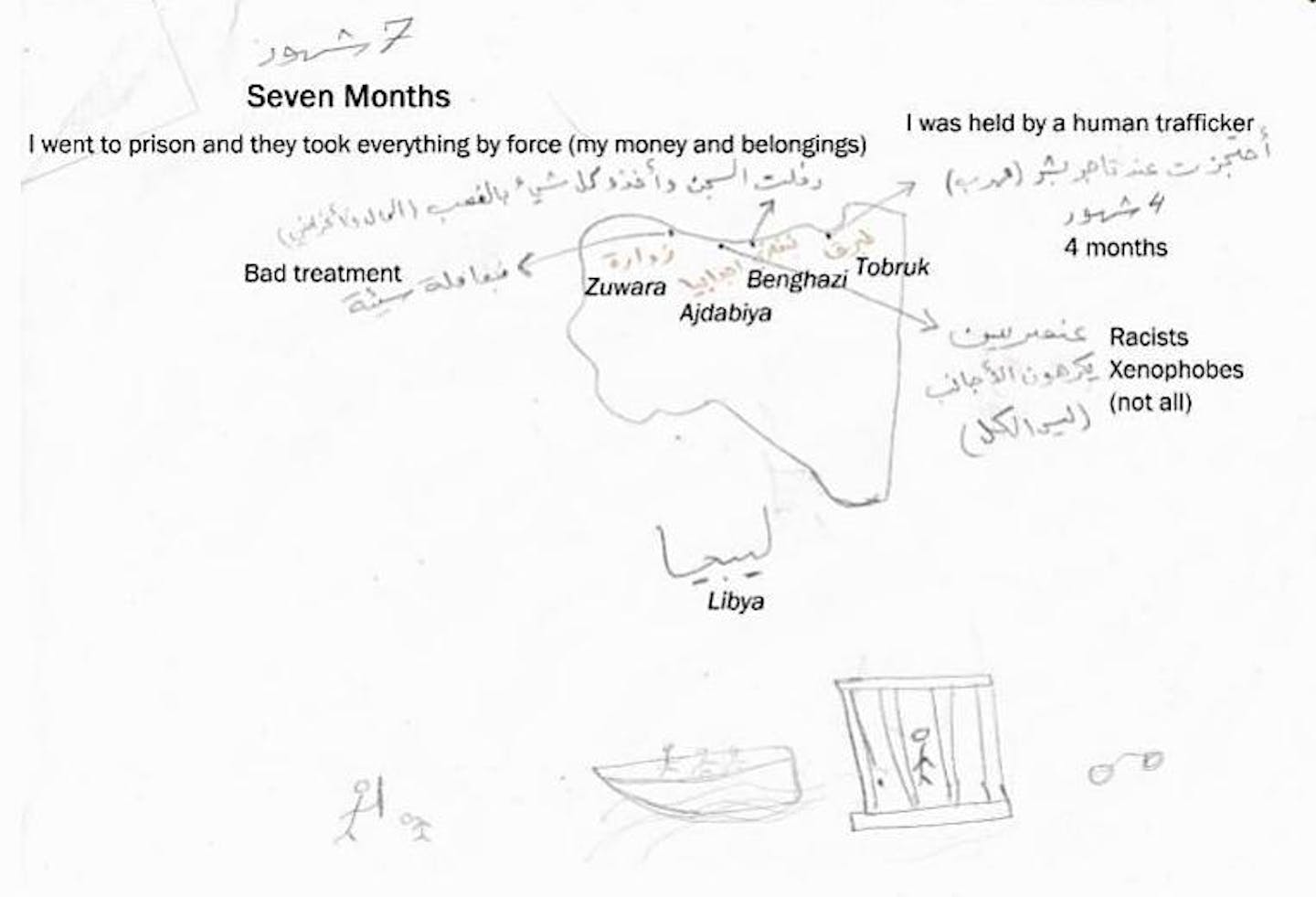

On his map, Mohamad illustrated this well, depicting the cumulative violence he had encountered along the Libyan coast from east to west: captivity in Tobruk by a “human trafficker”, imprisonment and theft in Benghazi, racism and xenophobia in Ajdabiya, and mistreatment in Zuwara – where he finally managed to flee by sea.

Mohamad’s illustration shows, from right to left, the chain of events that led him from imprisonment to the boat:

To take to the sea, however, first one must gather a considerable sum of money. Participants mentioned borrowing from their families – US$2,000, $6,000, even $10,000 – to buy a place on a boat. This place was also sometimes obtained after doing forced labour in prison conditions, or in exchange for promising to be the person who steered the boat.

When attempts to cross the sea are thwarted by interceptions followed by forced returns to Libya, the original sum must be paid again. As one participant explained: “They scammed me first for US$2,000, then $3,000, and the third time I paid $5,000.”

Some participants also described their living conditions in so-called “game houses” – the buildings where people who had paid for their crossing wait for the signal to depart. These stays can last from several days to several weeks, with varying amounts of supplies and conditions depending on the network and the sum that has been paid to get there.

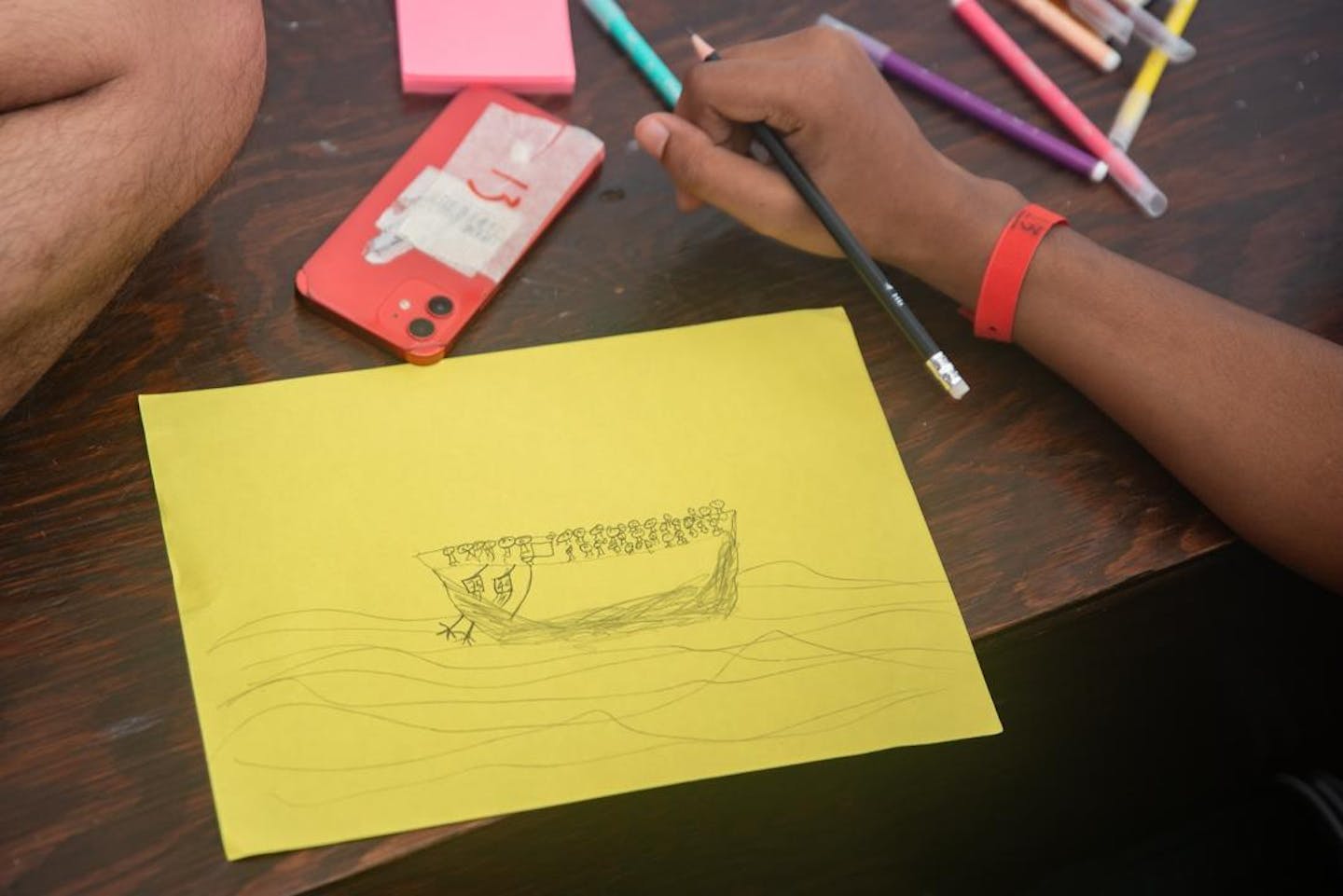

However, everyone shared the same realisation upon their first attempt to cross: the boats were unfit for navigation and dangerously overcrowded. But as Koné explained, at that stage it was generally too late to turn back:

We started from a beach near Tripoli at 4am. They made us run into the water: ‘Go, go!’ It was too late to change our minds.

The moment of rescue

Departures from Libyan beaches often happen at night, meaning it’s only in the morning that the vastness of the sea becomes visible. The on-board survey helped reveal how people on boats in distress often feel a sense of disorientation at the moment of rescue. One participant mentioned “the simple joy of having found something in the water”, when recalling his first impression of the Ocean Viking appearing on the horizon.

Others described how their perceptions were distorted by the navigation conditions, or the distressed nature of the boats they had travelled in. A Bangladeshi man who had boarded in the hold of a wooden boat recalled:

I was inside the boat; I couldn’t see or hear anything. I didn’t believe it was a rescue until I came out and saw it with my own eyes.

Charlie, the SAR team leader who coordinated that rescue, recalled his shock upon discovering 68 people aboard a vessel built for 20: “As we transferred them on to our RHIBs [rigid-hulled inflatable boats], more people kept coming out from under the deck, hidden.”

Jérôme, the deputy search-and-rescue coordinator on board the OV, confirmed the case of an “extremely overcrowded” boat, as was highlighted by the final rescue report: “They were really overcrowded! The alert had reported 55 people on board, but we actually found 68 because some were hidden under the deck.”

A distressed boat adrift

Drawing on the questionnaire, cartographic workshops, and targeted interviews, I attempted to reconstruct this rescue with both the rescued individuals and members of the crew.

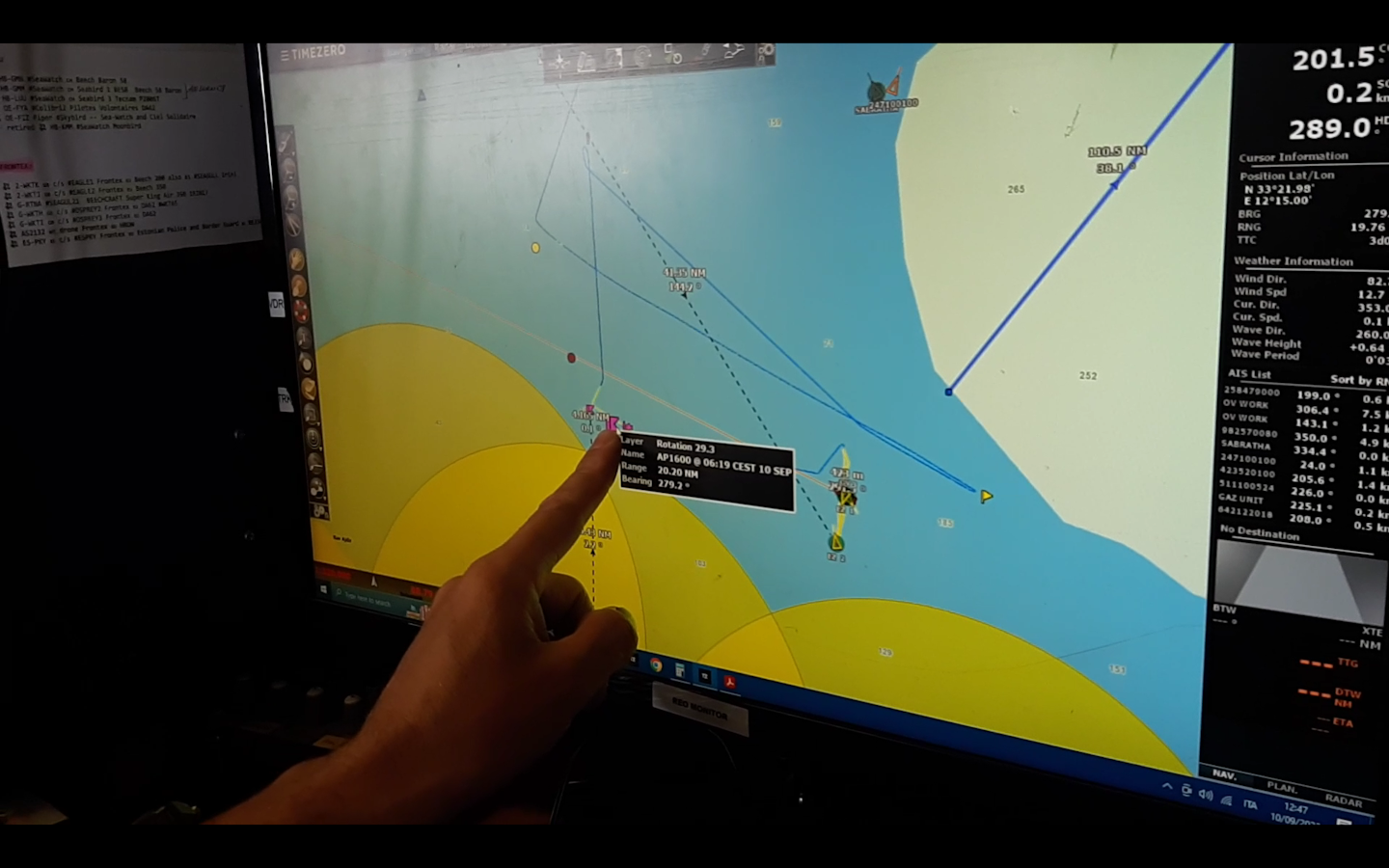

In the OV’s bridge, using the monitoring screen as support, we retraced the positions of the boat in distress throughout its search. That morning, the alert had been given by Alarm Phone, a citizen hotline operating continuously from both shores of the Mediterranean to relay and monitor cases of boats in distress. Jérôme recalled the moment when the decision to launch the search-and-rescue operation was made:

We got a position at 6.19am. We tried calling Tripoli several times, no answer. We said: ‘We’re going anyway, we’re very worried.’ We sent the official email saying we were going.

In our reconstruction, the OV headed for the reported position in international waters off the Libyan city of Zuwara. Shortly after, our radios set to the watch channel crackled: “We generally wake everyone up when we’re within ten miles, because that’s the distance at which we can spot them with binoculars. And at 6am, the first light of dawn appears”. The search for the boat in distress, however, soon became complicated:

With the first data – the boat’s departure point and second position – we had an idea of their speed: we thought they were going five knots. So we thought we’d find them at this next position. But once we arrived, we started tearing our eyes out – they weren’t there!

The calculations made during this search phase integrate multiple factors: the different positions received (when there are any), the presence or absence of a functioning engine, and the weather and sea conditions, as Jérôme explained:

I think they must have gotten lost and gone off course. With the sea and the wind in their faces, I think they couldn’t see anything they were doing. They were just fighting against all that.

Confirming this hypothesis, many of the people rescued that day arrived on the OV’s deck suffering from dehydration and seasickness:

As we saw in the photos, they had really big swells and wind hitting them in the face. The further you go off shore, the more you’re battered by the sea … Plus, here the wind was enough to make them drift: they were heading straight back to Tripoli!

‘These boats shouldn’t even exist’

Despite the difficulties described during that rescue, it was considered a “low-risk” operation. Far more critical events are regularly reported, both by rescuing crews and rescued people. Over time, rescue teams have seen the quality of boats deteriorate, as Jérôme explained:“First there were wooden boats, then rubber boats. Now the worst are the iron boats.”

In 2023, hastily welded metal boats began appearing off the Tunisian coast. For seasoned sailors like Charlie who make up the rescue teams, the very existence of such boats on the open sea is scarcely conceivable:

These boats shouldn’t even exist. They have extremely weak structures. They’re handmade, badly and quickly put together; they’re just metal plates welded together. They have no stability – they’re like floating coffins.

For these maritime professionals, the concern is real: “We need to be prepared for this.” The sharp edges of these metal boats can damage the inflatable RHIBs, risking the entire rescue operation, as happened in September 2023 during a patrol on the Tunisian route, when the RHIBs had to be protected using whatever was available on board the OV – in that case, carpets.

Each new type of boat requires implementation of very specific techniques: the approach and positioning (known as the “dance”) of RHIBs around distressed boats; the communication methods needed to keep people calm; and the emergency care during their transfer to the mothership. All of this is meticulously studied to anticipate as many scenarios as possible.

In the crew’s daily meeting room, using a model built by SOS veterans to train for simulations, Charlie explained the techniques developed to approach each type of distressed boat, whether made of fibreglass, wood, rubber or metal.

In the latter case, he emphasised the critical implications of a rescue going wrong: “Iron boats can capsize at any moment and sink quite rapidly, straight down. In that case, the scene would be a massive MOB!” – a “man overboard” alert involving numerous people going into the water. This was illustrated by the small blue objects scattered across Charlie’s model.

Drowning rather than being captured

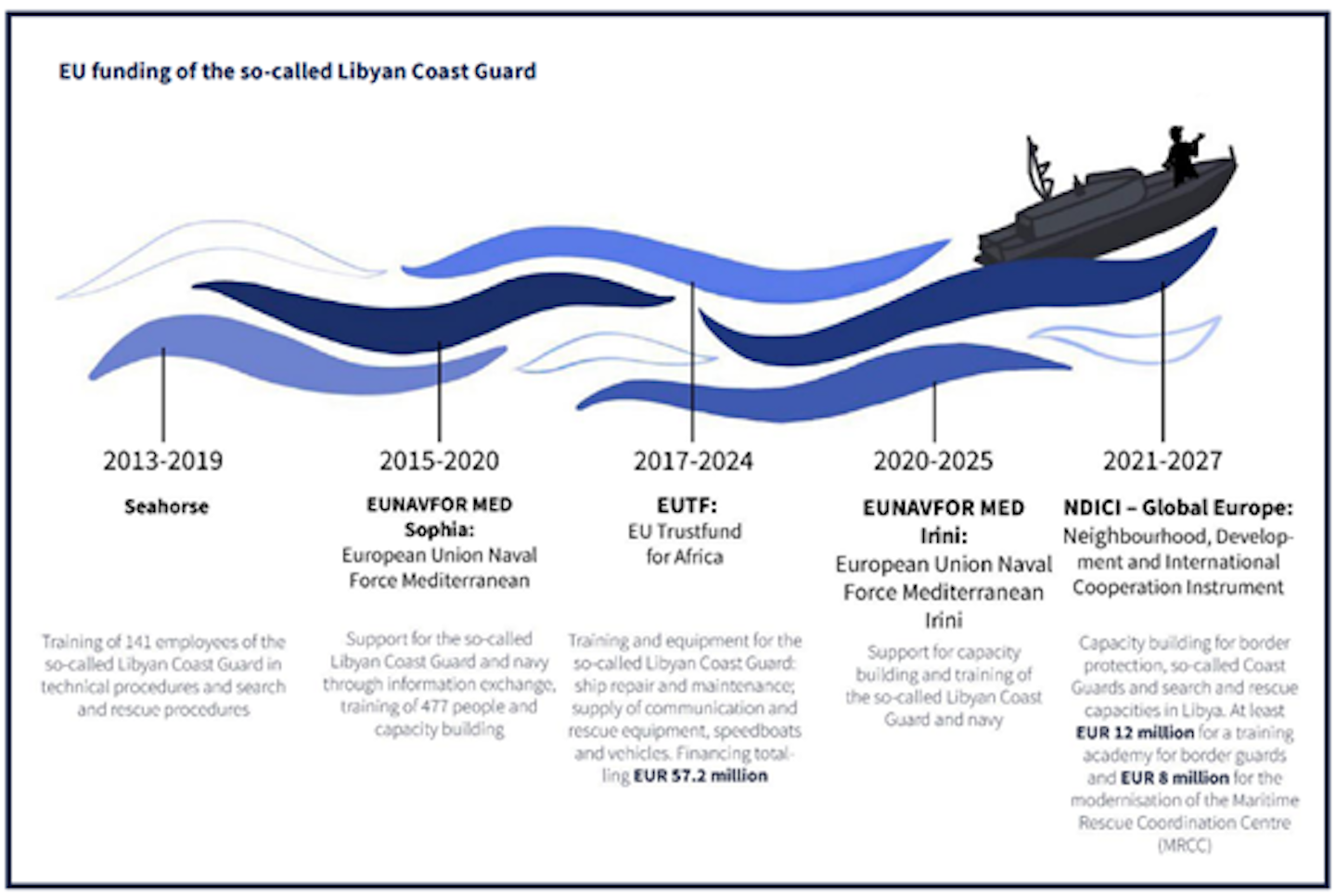

Another factor which has made rescue operations increasingly unmanageable is the activity of groups within the Libyan search-and-rescue region, created in 2018 with EU support. Two authorities are tasked with coastal surveillance in the this region: the Libyan Coast Guard under the Ministry of Defence, and the General Administration for Coastal Security under the Ministry of the Interior.

The numerous illegal and violent acts attributed to these Libyan groups at sea have justified the growing use of the term “so-called Libyan Coast Guard”. Yet these groups receive abundant support from the EU and several of its member states.

On board the OV, testimonies abounded regarding the perilous manoeuvres of these Libyan actors at sea – explicitly aimed at thwarting the rescue operations. “I’ve seen them make crazy manoeuvres,” said Charlie the SAR team leader, “trying to make the rescue as hard as possible, to make it impossible for us to rescue people – shouting, screaming.”

Several micro-scenes of this kind were reconstructed during our workshops and survey, leading to similar observations and recollections from both the crew and rescued individuals:

They drive as close and as fast as possible to create waves. They get in the middle of our way or interfere near the mothership.

When Libyan actors are on scene, the surge of emotions linked to the arrival of rescuers can turn into panic and jeopardise the success of the rescue. Almost a third of our study participants expressed a negative perception at the sight of a ship on the horizon, associating it with the fear of being intercepted and pushed back by Libyan groups at sea:

In the distance, we didn’t know if it was a rescue boat or the Libyans. It was huge stress on board; people were screaming, children were crying. We were ready to jump.

The presence of Libyan authorities was often perceived as a greater danger than the risk of drowning. “For me,” said one participant, “the danger is not the sea, it’s the Libyan authorities.”

This fear is easily explained among people who have already experienced one or more interceptions. Some participants mentioned violence during their forced return to Libya, including beatings, armed threats, theft of money, deprivation of water and food, or even deadly acts:

My first-time sea crossing, the Libyans shot the engine, the fuel burned and exploded, the people next to me died.

Moreover, the close ties between the “Libyan coast guards” and militias or mafia networks are notorious. One respondent said of the General Administration for Coastal Security (GACS): “There’s always a risk that the GACS, an armed group with masks, will take you to prison.”

Interceptions are generally followed by arbitrary detention in Libya (under inhumane conditions detailed in part two of this series). One participant told us: “I tried to cross four times but was caught and put in prison with my child; I suffered a lot.”

These reports, by both the OV crew and rescued people, are widely supported by international organisations, humanitarian groups and activist collectives monitoring the situation in the central Mediterranean. In its 2021 report, the UN Human Rights Council left little doubt about the chain of causality linking interceptions at sea to human trafficking in Libya:

The Libyan Coast Guard would … proceed with an interception that was violent or reckless, resulting at times in deaths … There are reports that, on board, the Libyan Coast Guard confiscates belongings from migrants. Once disembarked, migrants are either transferred to detention centres or go missing, with reports that people are sold to traffickers … Rather than investigating incidents and reforming practices, the Libyan authorities have continued with interception and detention of migrants.

By linking these maritime rescue scenes with the vast exploitation system organised from detention sites in Libya, it becomes clear that interceptions by the “Libyan coast guards” have become a strategy of capture. The central Mediterranean has thus turned into a battleground for protecting life and human dignity.

Read the final part in this series here, and explore an immersive French-language version of the series here.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Morgane Dujmovic, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS)

Read more:

- ‘We were treated like animals’: the full story of Britain’s deadliest small boat disaster

- Slave auctions in Libya are the latest evidence of a reality for migrants the EU prefers to ignore

- Migrants calling us in distress from the Mediterranean returned to Libya by deadly ‘refoulement’ industry

Morgane Dujmovic does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Reuters US Domestic

Reuters US Domestic KRWG Public Media

KRWG Public Media Reuters US Politics

Reuters US Politics El Paso Times

El Paso Times AlterNet

AlterNet NBC News

NBC News The Bay City Times

The Bay City Times CNN

CNN