I have always been fascinated by how Jane Austen depicts the physicality and health of her characters. All of her novels contain references to physical condition, ailments, or advice on wellbeing – indeed, the word “health” appears more than a hundred times throughout her six best-known works. These are not conventional medical descriptions, but they do display surprising accuracy and narrative consistency.

The prominence of health and illness in Austen’s novels begs the question: What if the drama of her writing lay not in romance… but in the common cold?

Austen’s interest in illness

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, illness played a major part in everyday life. Without antibiotics or anaesthesia, the smallest ailment could quickly become something more serious.

Medicine was based on theories such as humouralism, and treatments included bloodletting, tonics and purges. Doctors, apothecaries and quack healers existed and coexisted, but a lot of care – especially for women – was provided at home. Infections were common, meaning hospitals were a last resort.

Health recommendations tended to revolve around nature, fresh air, rest and bathing. Jane Austen advised daily exercise, contact with nature and a moderate diet as keys to good health. She enjoyed walks in the open air and was wary of excessive medical treatments. Her letters reflect a practical and balanced approach to physical and mental wellbeing.

Leer más: Fresh air has long been seen as important for our health, even if we haven't always understood why

It is believed that in 1815, when she went to care for her brother, she probably contracted tuberculosis. This degenerated into a kidney infection and eventually into Addison’s disease, which was unknown at the time. There is still some debate about the cause of her death. Disease, lymphoma, stomach cancer or even poisoning have all been proposed – though the last of these may venture into the realms of conspiracy theory.

Austen’s friendship with her brother’s doctor gave her a good basis for discussing ailments accurately: her novels abound with colds, rheumatism and, of course, the dreaded “chill”.

But what was the actual risk of walking in the English rain? There is no shortage of online debate about whether the high fever suffered by Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility after going for a walk in the pouring rain was bad luck or pure drama. Both Jane Bennet – in Pride and Prejudice – and Marianne end up ill after getting wet, with the latter left on the verge of death. Health warning, or plain old narrative device?

The dangers of the British climate

In the context of the 19th century, getting caught in the rain was no small thing. Today we know that it does not cause a cold on its own, but at that time it was believed that cooling the body could trigger serious illnesses. This concern was well-founded: without access to antibiotics or effective treatments, a mild respiratory infection could easily develop into bronchitis or potentially fatal pneumonia. For this reason, accounts from the period often treated these situations with a dramatic tone that, far from exaggerating, reflected a real fear of the consequences of simple exposure to cold and damp.

William Buchan – author of Domestic Medicine, a famous medical manual that began circulating in 1769 and was reprinted throughout the 19th century – was unequivocal: the British climate was a public health problem. According to him, there was no other place where the weather changed as much and as quickly as Great Britain. And these variations, he said, were some of the main causes of colds, because they interrupted the body’s perspiration.

Buchan particularly emphasised the risk of staying in wet clothes. Not only because of the cold, which was already a problem in itself, but because dampness could “penetrate” the body and aggravate the situation. Even the strongest could fall ill: fevers, rheumatism and serious ailments were commonplace, even among young, healthy people.

Of course, Buchan did not want anyone to stay home for fear of getting wet. But he did recommend acting quickly: changing clothes as soon as possible or, if that was not possible, at least keeping moving until dry. What should never be done – though many people did it anyway – was to sit out in the countryside or, worse still, sleep in wet clothes. For him, these were sure-fire recipes for illness.

Leer más: How Jane Austen’s landscapes mapped women’s lives

Illness as a literary device

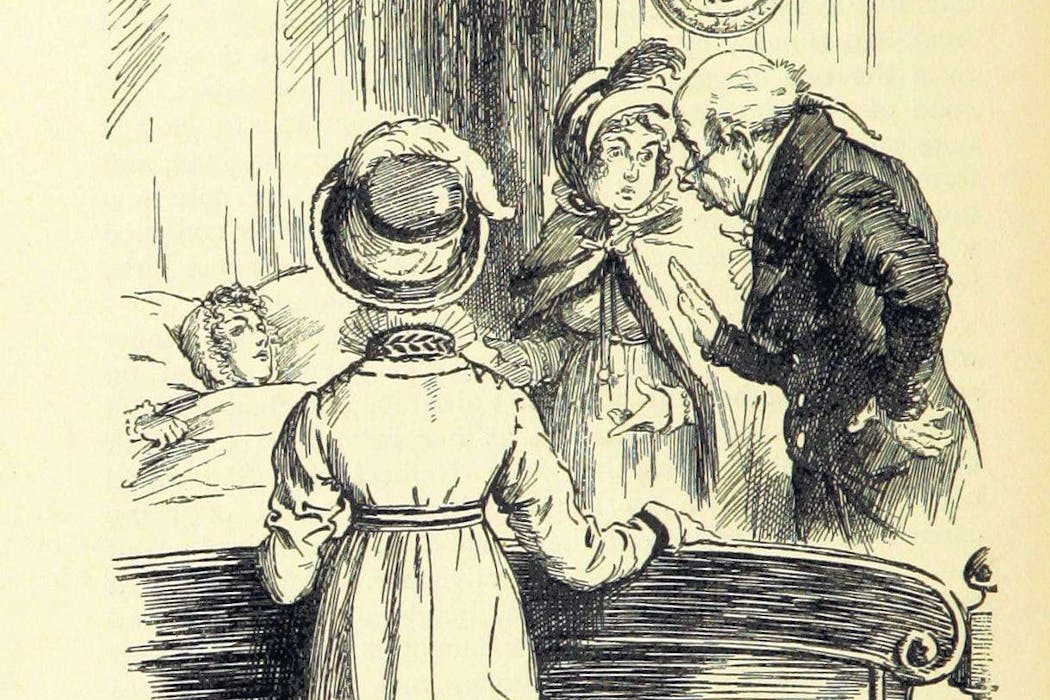

These maladies also reflect many social and gendered factors that affect women. In classical literature, illness is often a way for female characters to attract attention, express vulnerability, or even become more attractive in their fragility. Illnesses and accidents can disrupt their lives and change everything, sometimes forever.

In the 19th century, many women were diagnosed with what were known as “nervous disorders”, a term that encompassed vague symptoms such as fatigue, anxiety, insomnia and melancholy. It served above all to reinforce stereotypes of female fragility. Austen portrays different nuances of this ailment: Mrs Bennet’s theatrical “poor nerves” in Pride and Prejudice, Marianne Dashwood’s overflowing passion, the silent melancholy of Anne Elliot – the protagonist of Persuasion – and the resigned pallor of Jane Fairfax in Emma.

Mary Elliot, in Persuasion, resorts to feigned ailments to attract attention or avoid responsibilities such as caring for children, though her complaints – headaches, fatigue, indisposition – are not very credible to either the characters or the reader. Austen criticises this fictitious illness, which was typical of certain wealthy sectors of society where boredom and egocentricity were disguised as physical discomfort. This critical view also stems from her personal experience caring for her mother, whose health was fragile and variable.

So did Marianne Dashwood nearly die from a simple downpour in Sense and Sensibility, or did Austen bring her to the brink of death to change her fate? In her novels, illnesses and accidents not only generate drama – they also alter the course of the characters’ lives.

In Persuasion, Louisa Musgrove’s serious injury opens the way for another suitor. Jane Bennet catches a cold after riding in the rain, and her convalescence brings her sister Elizabeth closer to Mr Darcy. In Austen’s plots, fever often precedes the big romantic twist.

Leer más: Jane Austen and theory of mind: how literary fiction sharpens your 'mindreading' skills

The body as a metaphor

In Austen’s world, the body doesn’t just get sick – it talks.

Through fevers, fainting spells and colds, her novels give shape to repressed emotions, class tensions and gender inequalities. Illness serves as a metaphor for what changes, hurts, or simply cannot be said aloud. Austen did not view discomfort from the outside – she knew it, experienced it, and turned it into literature. Her characters suffer, but they also resist.

And they continue to speak to us today, with a lucidity that never fades. As Austen wrote, with her characteristic irony intact, in a letter from 1816: “I continue very tolerably well, much better than any one could have supposed possible”. We can surmise that she may have been referring not only to her bodily health.

In any case, we should all be careful not to get wet. Or maybe don’t – if Austen’s plots are anything to go by, getting caught in a downpour might be just the thing that changes the course of your life forever.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ana Fernandez Mosquera, Universidade de Vigo

Read more:

- Introducing Jane Austen’s Paper Trail – a new podcast from The Conversation

- Friday essay: ‘black bile’, malaria therapy and insulin comas – a brief history of mental illness

- Bonnets, speech bubbles and ‘cheeky easter eggs’: a graphic biography of Jane Austen is subtly sophisticated

Ana Fernandez Mosquera no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Raw Story

Raw Story Atlanta Black Star Entertainment

Atlanta Black Star Entertainment NPR

NPR People Top Story

People Top Story IFL Science

IFL Science Verywell Health

Verywell Health AlterNet

AlterNet Deseret News

Deseret News Reuters US Business

Reuters US Business The Hill

The Hill