“The night I was awarded my doctorate, I had sex with a stranger on the beach.” So opens Mariam Rahmani’s debut novel, Liquid – a provocative and irreverent appraisal of academia, marriage and the structures of power.

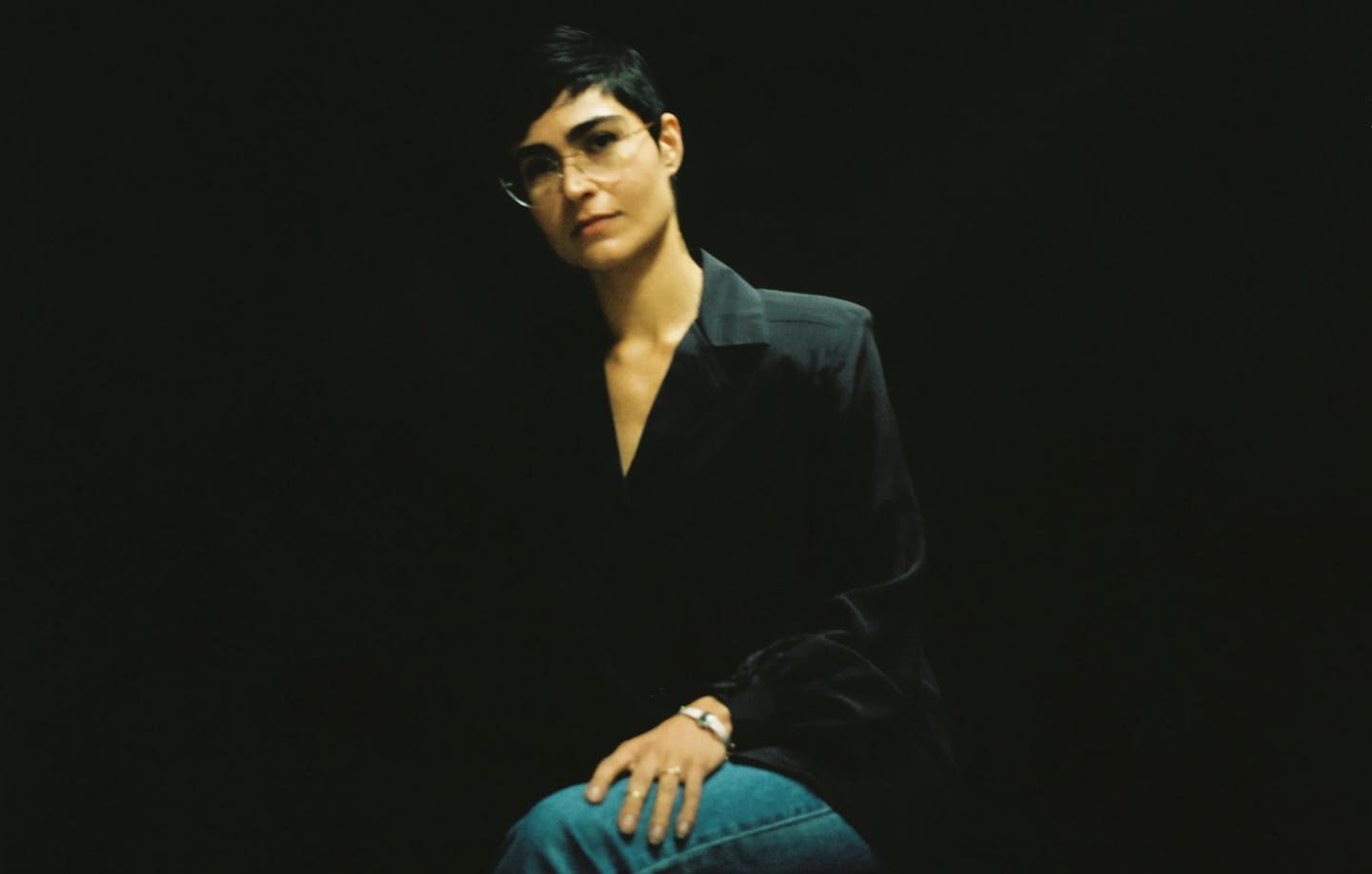

At once a rom-com and a literary novel (threaded with theory), Liquid seems, at times, to echo Rahmani’s own experiences – though she’s said her protagonist is “not me”. Her novel erodes the boundaries between genre and literary critique.

Review: Liquid – Mariam Rahmani (Doubleday)

The unnamed protagonist is a 31-year-old adjunct exhausted by the precarity of academic labour: “few abuses are more premeditated than a PhD.” She inhabits the neoliberal university and academic job market as both insider and outsider – a “scholarship kid” without familial wealth; a casualised teacher paid only during the semester. She muses:

A lowly adjunct, I haunted the library, trying and failing to turn my dissertation into a book, trying and failing to land a real job.

Rahmini, like her protagonist, is a literary academic (at Bennington College in the United States) and a translator. In Liquid, she exposes the structural violence of 21st-century universities, which are increasingly organised and run in a way that disregards the security and livelihoods of those who work and study there.

Romantic comedy is seemingly an unlikely genre for critiquing institutional power. That is, until you realise the structures of both the university and modern relationships, including marriage, are equally absurd – to the narrator, at least.

Rebellious to her core

The narrator’s father, who lives in Iran, is Shia Muslim; her mother is a Sunni Indian American, living elsewhere in the US. Both parents think she is too old and are hinting at an arranged marriage.

Rebellious to her core, she recalls spending her “teens and early 20s in hijab as a fuck you to post-9/11 America”. She decides to embark on 100 dates to find herself a rich spouse. She’s bisexual, so any gender will do: her goal is wealth – and specifically, an end to precarious living.

Differing cultural and generational understandings of marriage are threaded throughout. Regardless, the narrator’s cynicism about the institution is clear:

In both the West and the Islamic world, you traded goods, not feelings. Women offered sex and offspring, men food and shelter.

During her 100 dates, her father’s illness draws her back to Tehran, where the possibility of a different type of relationship – and better housing prospects – hovers on the margins. Despite her father’s condition, the city itself offers solace.

Tehran was almost at the same latitude as Los Angeles. The same sun slapped against my skin.

These familial and cultural dynamics sharpen the novel’s exploration of otherness. They force the narrator to explore what it means to move between worlds, and to live at once within and outside structures of belonging.

Bravado and irony

Liquid is, in one sense, a generic rom-com, referencing recognisable classics like When Harry Met Sally, Four Weddings and a Funeral and all things Nora Ephron.

Rahmani invites readers to consider how prepackaged romantic tropes function in relation to heavier topics, including the bonds of family, diaspora and death. “I found myself reciting my long-held prejudice against the friends-to-lovers plot,” her protagonist tells us, “which I considered the most unimaginative of all the rom-com subgenres.”

The difference with this rom-com, however, lies in how the protagonist records her encounters, using a self-conscious theoretical apparatus. Her PhD was, after all, on companionate marriage and the modern expectation spouses should be both lovers and friends. “What was marriage but tenure?” she muses, situating marriage in a world governed by contracts, exchange and profit.

The novel’s intellectual density is deliberate. References to psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan, German poet and writer Goethe and Palestinian scholar and activist Edward Said (among others) are dropped into the text with a mix of bravado and irony.

At times, this registers as excess – a performance of knowledge that risks exhausting the reader. Yet this is also the voice of the narrator herself: a woman trained to speak in theory, unable to shed the performance of erudition, even as she critiques it. “No one was willing to pay for the educators who squeezed Tolstoy-reading, Kiarostami-watching, Hartman-quoting artists out of the ignorant pipsqueaks who walked through our classroom doors.”

Anyone who has stepped into the university classroom and fought to teach the humanities against the odds knows this feeling all too well.

Taking risks

Liquid takes some risks. The protagonist’s self-regard and intellectual posturing are frequently unlikeable and will likely alienate some readers. The novel is also deliberately bawdy, with somewhat dirty humour. In the toilet at an expensive degustation restaurant, the protagonist admits she

climbed up onto the seat and squatted with my tights bunched down. It took all my core strength not to fall in. Apostate or not, I still had some Muslim in me – I’d sooner eat my own flesh than sit on a Western toilet in a public bathroom.

Occasional forays into footnotes and tables disrupt the flow, sometimes superfluously – but they underscore the novel’s refusal to conform. Yet to dismiss these elements as flaws is to miss the extent to which they illustrate Rahmani’s point. Liquid refuses the smoothing over of contradictions; Rahmani wants readers to experience the oscillation between excess and emptiness, theory and rom-com banter.

Liquid will frustrate readers seeking the comfort of rom-com conventions. But for those willing to accept its refusal of genre purity, the novel offers something rare: a narrative that insists on the need for both pleasure and critique.

Rahmani has produced a novel that destabilises its own forms, even as it indulges them. It critiques academia while revelling in its language, satirises love while longing for it. Liquid is a rom-com for the age of precarity: one that makes us laugh while reminding us love, like knowledge, is always entangled with power.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Astrid Edwards, The University of Melbourne

Read more:

- Charlie Kirk talked with young people at universities for a reason – he wanted American education to return to traditional values

- ‘Liberal’ has become a term of derision in US politics – the historical reasons are complicated

- Friday essay: Gertrude Stein got famous lampooning celebrity culture – but not everyone got the joke

Astrid Edwards does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

People Books

People Books Lubbock Avalanche-Journal

Lubbock Avalanche-Journal The Daily Bonnet

The Daily Bonnet CBS News

CBS News The Hill Politics

The Hill Politics The US Sun Health

The US Sun Health NBC10 Philadelphia Sports

NBC10 Philadelphia Sports